The Oldest Iron,

The Troon Clubs

& Early Club Evolution

This article is best viewed on a larger screen.

You can quickly view footnotes by just clicking on them and then clicking the Return ↩ icon to go back. Section headings have the same icon for easily returning to the top menu.

This article was researched and written by Jeffery B. Ellis, author of And The Putter Went Ping ; The Clubmakers Art: Antique Golf Clubs & Their History; and The Golf Club: The Good, The Beautiful & The Creative.

Copyright Jeffery B. Ellis 2024

Irons

1.1The Oldest Iron—A Monumental Discovery

Understanding and documenting the history of golf equipment has been my life’s work for upwards of four decades. Three years after attending my first golf auction in the UK, in 1984, I began writing The Clubmakers Art: Antique Golf Clubs and Their History which in 1999 Golf World named as one of the top 10 books written in the 20th century and in 2018 Golf Digest named it to their list of the 50 golf books every golfer should read. Since then, my passion for the fascinating world of antique golf clubs has only grown stronger. As a historian, piecing together the puzzle of golf club evolution—understanding who made what, when, why, where, and how—is my central focus. I greatly value historical documentation, but I also find inherent credibility in what antique clubs themselves tell us.

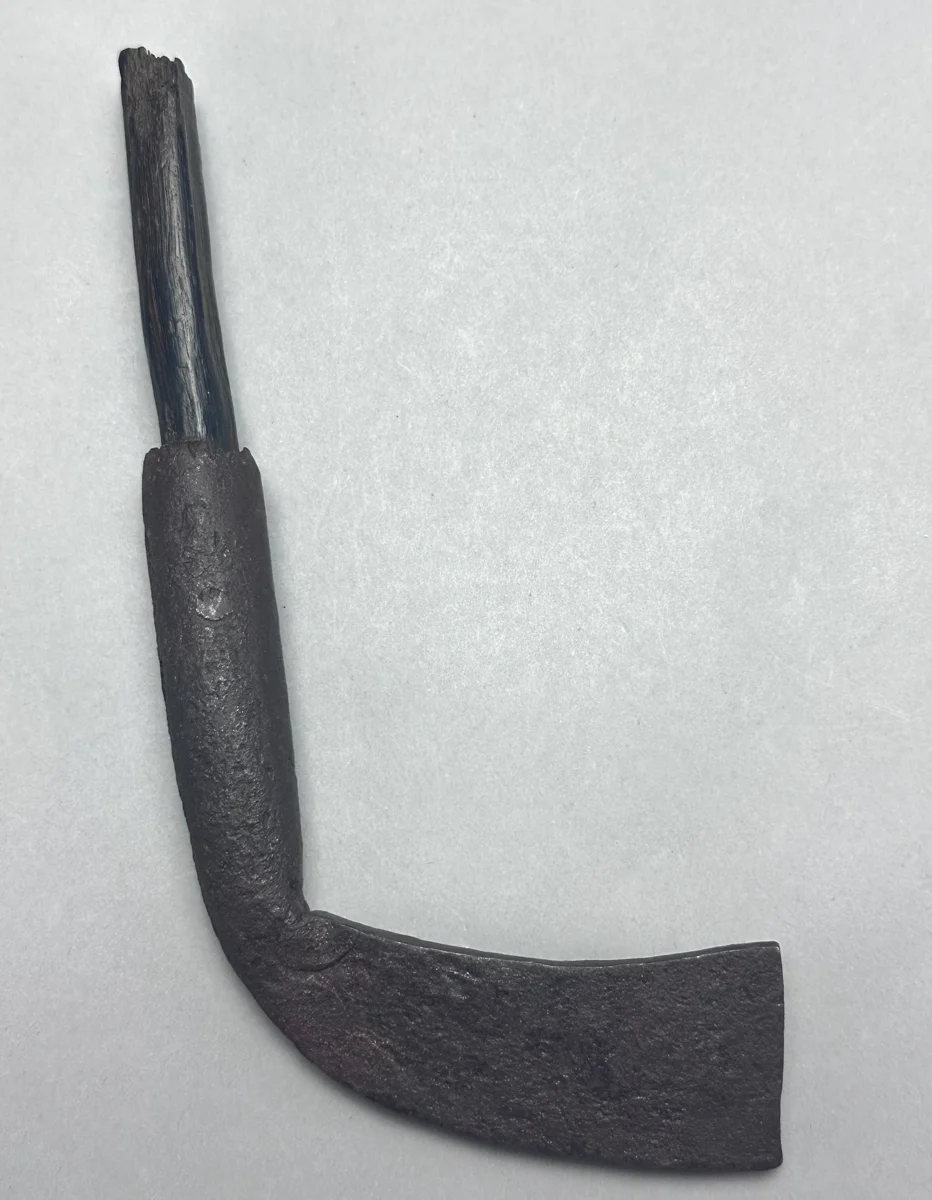

Golf dates at least as far back as 1457, the date of the oldest known written reference to the game. Because golf is so old, I have often been asked what is the oldest golf club? I now have a new answer. It is likely the iron clubhead shown at the top of this report—and I believe it dates to the 1500s.

After studying this clubhead on many occasions over the past two decades, I can confirm that it is the oldest iron I have ever seen, heard of, or read about. After languishing in two small collections for the past three decades, and half a millennium of being lost to civilization, it is time to bring this remarkable club to the world’s attention.

Throughout this report, I show why I date things the way I do. The factors behind my logic and examples that lead my reasoning are presented. This report includes ancient clubs that serve as verifiable benchmarks for dating other antique golf clubs. In addition, a number of factors such as blade shape, head construction, hosel construction, and structural refinements that contributed to my assessment of a club and its age will be documented. As clubs evolved over the centuries, their construction became more refined, though it was a slow process.1

Not everything is known about antique golf clubs. No doubt there will be further discoveries and documentation from centuries past that will come forward. Therefore, I follow the principle of Occam’s razor, which basically states the simplest explanation is most likely the correct one. In the instance of golf club evolution, the simplest explanation needs to include all the facts that are known about antique golf clubs, as the clubs themselves serve as a record of their own development. Picking and choosing certain facts and ignoring or replacing others with conjecture to fit a predetermined theory is not the best method. Of course, the simplest explanation is not always the correct one, but when you hear hoofbeats, in the large majority of cases it’s best to think horses, not zebras.

1.2Background ↩

This iron first came to light when it sold at a small Scottish auction back in the 1990s. Nobody in the room knew what to make of it, me included. The auction catalog (which is only as accurate as the cataloger and historically lacks context and detail on a club’s specifics) had a low estimate for the lot and no accompanying image. At the time, I did not understand what I was looking at, so I passed on the iron.

The iron was purchased for a relatively small amount by a dealer who liked it and kept it for several years. In 2001, he sold it for a relatively large amount to a collector I know in the US. Since then, I have been allowed to study this head on many occasions and even have it X-rayed. My initial skepticism about the age and authenticity of this iron is now gone.

To understand where this club fits in the evolution of the oldest irons is to determine its relative age—if it is the oldest. Therefore, a review of that evolution is in order.

During the 1500s, 1600s, and 1700s, the evolution of tools, household items, and everyday implements was relatively slow. Changes were characterized by incremental improvements rather than rapid innovation. Most things evolved slowly while remaining distinctly similar. Golf clubs were no different.

Of course, there have been relatively rapid watershed moments in the evolution of antique golf equipment, such as the change from the feather ball to the gutty ball, long-nose woods to bulgers, and wood shafts to steel shafts. But for the oldest irons made prior to 1800, evolutionary change was primarily stylistic and occurred in a slow, gradual fashion over long periods of time.

Before proceeding further, the reader should note that the images in this report are not to scale, so any visible difference between the size of one head or hosel to that of a neighboring iron in a separate image is not entirely accurate, though oftentimes quite close. Also, many of these iron heads are quite dark, yet these are color images. This is because these irons are made from wrought iron. The deep brown and sometimes blackish surfaces show the natural patina that often forms on wrought iron depending on factors that include the environment in which it has existed. Forged steel will typically have rust that is reddish-brown or orange-brown.

1.3Indicators of Great Age ↩

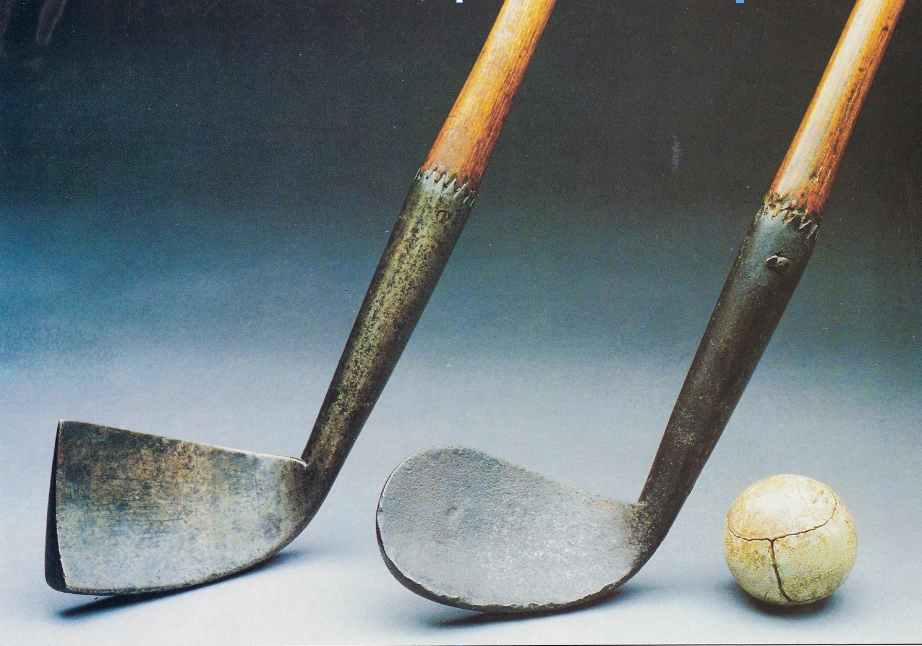

The first two irons shown below are the two Troon irons. After residing for over a century at the Royal Troon Golf Club, they are now on display at the R&A World Golf Museum in St. Andrews.

These next two irons below were both once the property of the Earl of Wemyss. Today, only the larger iron remains with the Earl.

Prior to the early 1990s sale of the clubhead under discussion, the four irons above plus the two below were considered by many to be the oldest known. They stood out in a unique class of their own. These irons have several important identifying characteristics that indicate they are extremely old, but the primary and ever-present feature that sets them all apart as the oldest irons is the significant curve at both ends of their topline. Of these six irons, only the two Troon irons can be dated with reasonable accuracy. Consequently, similar clubs are dated from them. As I document later in this article, abundant evidence indicates that the Troon clubs date prior to the reign of King Charles I that began in 1625 but after his birth in 1600.

During the past 35 years, I have become aware of three more irons that share the same traits as the original six oldest, including a significant curve at both ends of their topline. And that’s it. There are no others.

The spur toe on five of the irons above is not something that would have been included on the first irons ever made. The spur, the pointed protrusion at the base of the toe, was supposedly designed to help golfers play shots using the toe of the club, to strike a ball stuck in a narrow track or between stones.

Of the two Troon irons shown earlier, one had a spur and the other one did not. These two irons were made by the same maker but their functions were different. Furthermore, a golfer only needed one club with a spur in order to strike a ball between rocks, etc. Consequently, a spur, often considered the primary indicator of the oldest clubs, is but a feature that is only found on some of them.

1.3aBlade Curve & Hosel Sweep ↩

The key indicator to determine the oldest irons is blade shape. The curve given to both the sole and the topline is the uniform feature found on the irons above, both those that do have and do not have a spur toe. As shown above, when these irons are properly soled their toplines curve up as they approach both the toe and the hosel. The upward curve/sweep where the topline transitions into the hosel is a prime indicator of great age found on the oldest irons as is the upward sweep of the topline as it approaches the toe.

With the passing of time, the upwards sweep of the topline towards the hosel evolved, becoming less and less until it transitioned into a sharp crease where the topline runs straight into the side of the hosel . This crease is found on all the square-toe irons that were made thereafter, none of which have a spur or a topline that curves up at both the toe and hosel.

Hosel width and length are also important indicators, but not by and of themselves. The hosels on the irons above are definitely large in length and width, some more than others. Even after the transition from the spur toe to the square toe era, irons continued to feature hosels with similar large dimensions. Therefore, hosel length and thickness by and of themselves do not tell us all there is to know about the age of an iron. The length of the hosel depended on the iron bar chosen by the blacksmith and the desired blade length, which could vary based on circumstances or preferences. As a result, there is a consistent variety of hosel lengths found throughout the spur-toe and square-toe eras.

Like hosels, blades also varied in length and size, as shown above. Therefore, blade size alone is not a definitive indicator for determining the age of early irons.

Again, a curved topline is found on all of the oldest known irons. Curved toplines are not found on the spur-less square-toe irons with hosel creases that followed in their wake, as shall be shown.

1.3bTopline Curve Transition ↩

Similar to the previous irons shown, the left-handed spur-toe iron above features a topline that sweeps up into the hosel and curves up towards the toe. However, the sweep at the toe is less pronounced, and the sweep at the hosel is small and short. While it has a spur on the toe like the other heavy irons shown earlier, it has a flat sole unlike all the other irons. Following its introduction, the flat sole became an option, with some later square-toe irons also being made with rounded soles.

The iron above left is a heavy iron, but it lacks the spur toe found on all the earlier heavy irons. It has an even smaller sweep up at both the toe and hosel. In fact, the hosel sweep has almost become a crease. Its sole is flat much like the other two irons above. This iron is slightly more refined and not as old as the other irons that precede it in this report.

The topline on the iron above right does not sweep up at the toe nor the hosel. The hosel has much more of a crease than a sweep. But the crease is not sharp. The crease is not finished the way that it is on the irons that follow.

1.4Square Toes, Flat Toplines, and Sharp Hosel Creases ↩

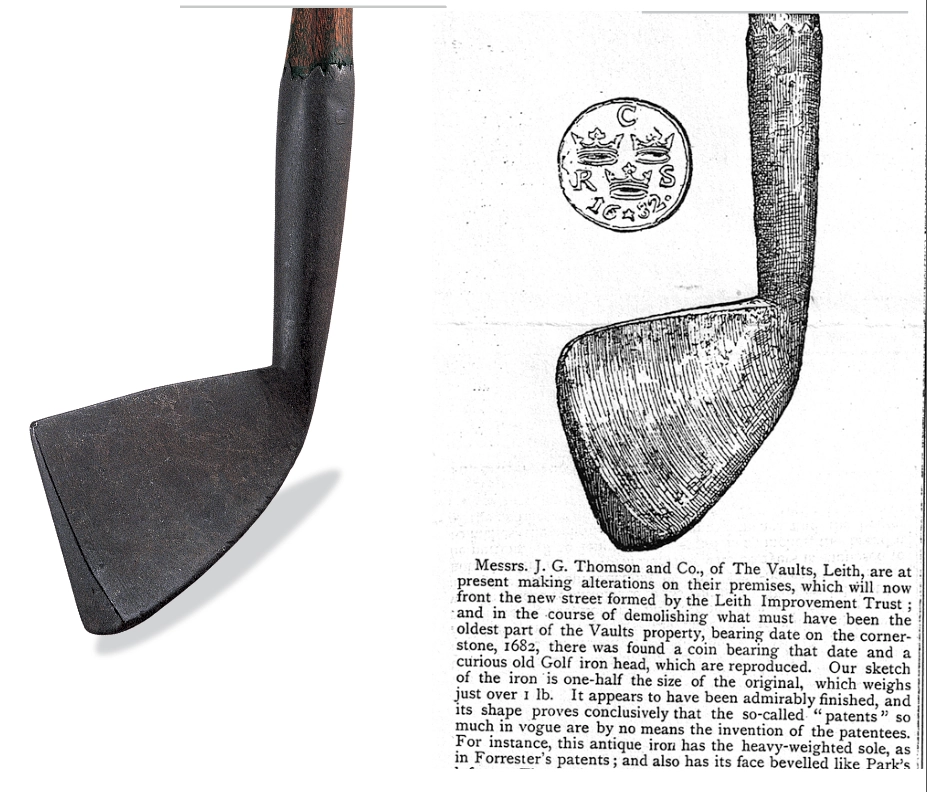

The iron head shown above left has a sharp crease where the top line of the blade intersects the side of the hosel, providing a reasonable match to the drawing of the iron shown on the right. Published in the May 29, 1891 issue of Golf, this drawing depicts the iron head discovered during the excavation of a building in Leith, Scotland. The cornerstone bore the date 1682, and a coin dated 1682 was recovered along with this iron clubhead. The magazine deemed this find important enough to document.

In 1682, it was common practice in both Scotland and England to include artifacts when installing cornerstones, often referred to as foundation stones, in significant buildings. This tradition held ceremonial and cultural importance, reflecting the customs and life of the time. Artifacts typically included coins, newspapers, and other items of historical significance that were meant to provide a snapshot for future generations. This practice was essentially creating a time capsule, preserving a record of the present for posterity. Including such items in cornerstone ceremonies commemorated the building's construction and gave the people of the time a voice in the future.

When construction began on a new clubhouse for the R&A in 1853, no clubheads but two golf balls and a few dated coins were placed under the foundation stone. The July 14, 1853, issue of The Fifeshire Journal reports that “two balls, one of leather and another of gutta-percha,” were placed into a cavity and covered by the “foundation stone” as part of a grand ceremony with thousands of onlookers. Also included were three current newspapers, a few “current coins,” an inscription, and a few other items.

Artifacts like a clubhead together with a dated coin can indeed provide a tangible glimpse into the past. This explains the magazine's interest in the discovery of this iron head—the world now had a benchmark for what an iron from the late 1600s looked like.

Given that the magazine gave straightforward credibility to the find shortly after it occurred and went to the effort of documenting it—having the iron and coin sketched and presenting the iron as contemporary with the 1682 coin and cornerstone—it's reasonable to conclude that big, heavy square-toe irons with a sharp blade crease and no spur were being made before 1700. The editors and staff at Golf were alive when this iron head was found, so it is difficult to dispute their presentation. Dating the iron to the 1682 coin and cornerstone aligns with the traditions of foundation stones and cornerstones and corroborates my research on early antique golf clubs.

The three square-toe irons shown above have a sharp blade crease at the hosel. Such sharp creases and relatively flat toplines became the standard for square-toe irons throughout the 1700s.

One thing about irons is the heads will never break. Only the shafts are at risk, and a head was easily reshafted. Consequently, during the 1600s and 1700s individual irons could remain in use for decades if not a century or more before falling into disuse.

Not only were irons expensive, there was also no “game improvement technology” to motivate the golfer to change their clubs. The key element was simply to have clubs! Of course old irons evolved, but, again, it was slow. After all, instead of being used for distance shots, irons were used as rescue clubs when the ball was in sand, stones, or high grass—where a wood-headed club either would not work or was at greater risk of damage. During the feather-ball era, it was considered reprehensible to use an iron on short grass.

1.5Round Toes ↩

Square-toe irons sometimes had their top and bottom corners slightly rounded. It was thought rounding the sharp corners would prevent the square toe from scratching or damaging the wood clubs the golfer or caddy might be carrying (golf bags were not in use during the feather-ball era). Eventually, irons with entirely rounded toes entered the game. By the mid-1700s, round-toe irons coexisted with square-toe irons, as shown above, and were nearly identical in every respect except for their toe shape. Primarily the blades were evolving from square toe to round toe.

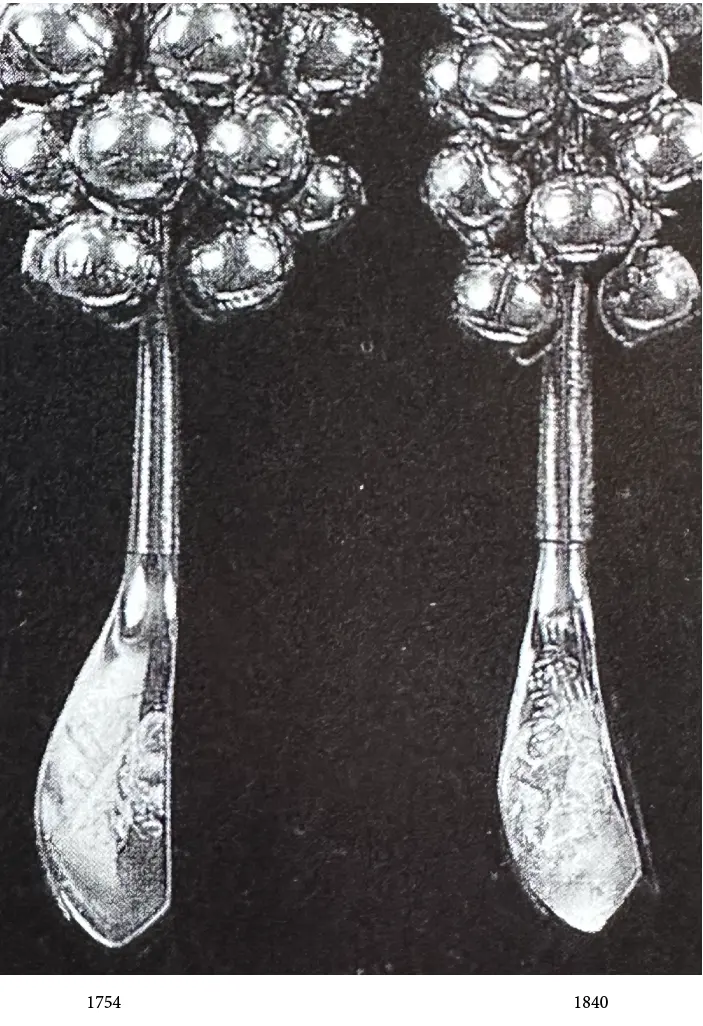

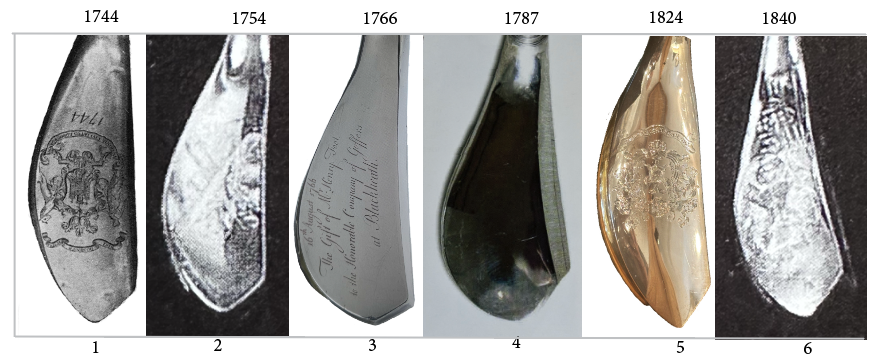

These four round-toe heavy irons look quite similar but have notable distinctions. They are different in hosel length, hosel thickness, hosel nicking, and blade size. Everything about the hosels on irons 1 and 2 is slightly smaller than the hosels on irons 3 and 4. By the end of the 1700s, the refining of hosel and blade size was underway, both becoming gradually smaller across the entire 19th century. Both heavy and light irons were becoming smaller and smaller, changing into the lofters and cleeks of the 1850s which also continued to downsize as they approached the 1890s. Note that a few old square-toe irons were still in use at the end of the feather-ball era. The earliest golf clubs, like tools, could be passed down from generation to generation.

- Iron 1 has a blade that matches up well with the blade on irons 3 and 4, its hosel is distinctly shorter and thinner and possesses the least prominent nicking at the top of the hosel. It dates circa 1820.

- Iron 2 is a “ringmaker” iron, with an engraved ring around the top of the hosel. The ringmaker (his actual name is unknown) was a prolific blacksmith given the fact that a number of his irons remain. This club also dates from the early 1800s.

- Iron 3 has an even longer and thicker hosel with stronger nicking than is found on the two irons to the left. It dates to the late 1700s.

- Iron 4 dates to the mid 1700s. It has the longest and thickest hosel, the most prominent nicking, and the largest head of the group.

Every one of these round-toe irons is an absolutely phenomenal club. Clubs this old are extremely scarce, and these in particular are larger than life when viewed in person and given a waggle. It can be hard to believe that golfers centuries ago actually swung such monsters.

1.6The Oldest Iron Revisited ↩

Like all the irons shown earlier, the oldest iron has a curved blade, both topline and sole. Its blade is shallow, not as tall in the face as the heavy irons shown earlier, and very much in character (except for its 1-inch thick pipe of a hosel and heavy weight) for what would later become known as a “light iron”.2 However, unlike every known antique iron clubhead made for centuries prior to Bussey’s steel socket iron patented in 1890, the head on the oldest iron is made from two pieces. In the image above, the connection between the two pieces—the blade and the hosel—is visible where the heel of the blade is overlapped by the iron from the base of the hosel.

1.6aTwo-Piece Head ↩

The two closeup images above show the hammer-welded connection between the two pieces of iron—the blade and the hosel—used to construct the head. Evidence of the hammer weld is visible on the front of the blade above left and especially on the back of the blade above right. Those are not cracks, that is metal from the hosel as it overlaps the heel end of the blade on both sides. The blacksmith simply did not finish off and blend the weld as nicely on the back of the blade as he did on the face.

In the image above left, the top corner of the blade that is closest to the hosel can be seen. While many ancient irons have hammer welds on the back of their hosel and behind the blade, none have a weld on the front of the blade like this club. A head made from one piece of iron welded together on the back of the hosel/blade would be solid on the front of the blade. There would be nothing there to weld together, let alone form a weld down to the sole like it exists on both the front and back of this head.

In the image above, the tip of the corner of the blade is visible next to the hosel, and the blue arrows identify the hammer weld that connects the extension from the hosel to the front of the blade.

The image above shows just a portion of the overlapping hammer weld, indicated by the blue arrows in the preceding image. The blacksmith made a smoother weld here than on the backside, likely because the face of the blade is what contacts the ball, rather than the back.

The blue arrow points to where a small “ear” from the weld on the back of the blade overlaps onto the top of the blade.

The two blue arrows above indicate that the metal from the small ear indeed overlaps onto the top of the blade. This overlap secures the blade at its top to the hosel.

The blacksmith's hosel weld on the back of the blade is shown above. The angle of this weld as it moves towards the sole matches the angle on the front of the blade. It would neither be necessary nor possible to have three hosel welds that border and attach to the blade on a one-piece iron head, as a one-piece head has only a single weld that closes the length of the hosel. The blade and hosel are integrally formed from one piece of iron. On a two-piece head, however, hosel welds on three sides of the blade would be required.

In the 1500s wrought iron was quite valuable—the stuff to make tools and weapons—so combining two smaller pieces would make sense in terms of managing one’s resources. Iron was so valuable that even scraps on the floor would not go to waste. They would be forged back together and used to make something else.

However, making a head from two pieces allowed for the possibility that the weld might break. If that happened, the blade might fly off and literally injure or kill somebody. As history appears to indicate, two-piece heads were extremely short-lived. It likely did not take long before they were found to be unacceptable be they made due to a material shortage or standard design.

Eliminating two-piece heads from the game was an evolutionary change even if one-piece heads initially coexisted with two-piece heads. This is the only known iron with a two-piece head, evidence this club was made when golf was in its infancy.

Below are two more views that show the backside of the hosel where it connects to the blade.

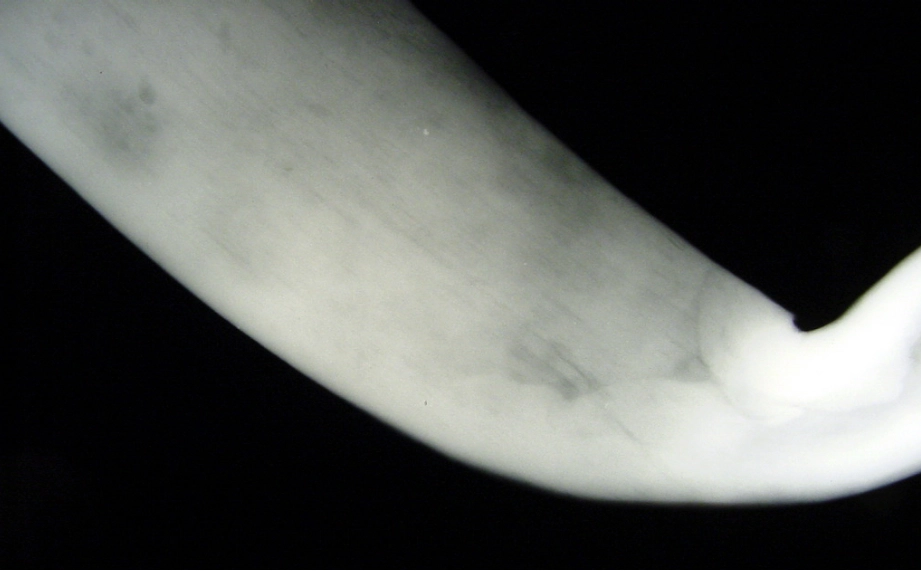

1.6bLaminated Blade ↩

In a discussion regarding the magnified image above, Paul Thorne, a master blacksmith with extensive knowledge of blacksmithing and wrought iron, observed that the blade not only features an ear across its top to secure it but is also laminated. He further described the iron, as paraphrased below:

Notice the lines running from front to back across the top of the blade. In some areas, the iron between these lines has a slight bluish-greenish tint. These are lamination lines that naturally occur when two or more pieces of metal are hammered/forged together. The blue-green tint in some sections is due to slight differences in the chemical elements that make up the iron.

To create this blade, the blacksmith used lamination techniques similar to those employed in the production of Damascus steel during the Middle Ages. The blade was likely crafted from leftover scraps of iron. Half a millennium ago, iron was a valuable commodity and never discarded.

As shown in these magnified images of the blade, the topline is smooth where the laminations are visible. When the head was made, the blacksmith could have polished the topline to make it bright, like a knife blade, if desired. The blacksmith took the time to smooth the topline and highlight the laminations, demonstrating his skill as a blacksmith. (The laminations would have been more noticeable when the club was new.)

This is the only known iron with a laminated blade. This is a major feature that provides more evidence that this iron is the oldest known.

1.6cWrought Iron Radiograph ↩

As in prior images, the hammer weld that wraps the base of the hosel around the heel end of the blade can also be seen in this radiograph. A pointed corner of the iron used to make the blade is visible at the top of the blade next to the hosel. Also visible is the fibrous grain or slag of the wrought iron, which appears as very fine lines running across the blade. Unlike forged steel, wrought iron has a fibrous grain created by the refining and forging process. This grain is made up of impurities/slag in the iron. Wrought iron fell into disuse as a structural material beginning in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Steel offered superior properties and, by then, was easier to produce in large quantities.

1.6dHosel Layers ↩

These views of the top of the hosel show that there are two layers along much of this hosel. Specifically, an outer layer wraps around the inner layer for approximately half of the hosel’s circumference. This outer layer starts at the blue arrow on the left and ends with the blue arrow on the right.

When this hosel was made, it began as a length of iron that was flattened (with one side longer than the other in order to attach to the blade) and then formed around a mandrel. To close the hosel, the blacksmith would overlap the “beginning” and “ending” sides of the flattened iron and continue to work the overlapping material until it became increasingly thinner and finally worked into the metal underneath, thereby changing the upper portion of the flat bar into a round socket to accept the shaft. The lower, longer side of the initially flattened bar extended below the socket to enclose and hold the sides and end of the blade.

As seen in the images above, the blacksmith did not fully pound the overlap at the top of this hosel into the underlying material. This left the thin overlapping outer portion of the wrap exposed at the top of the hosel.

The nicking was made using a file, and because the outer wrap was so thin and not fully melded or fused into the inner wrap, some of the nicking on the outer wrap has been lost.

Above left is a closeup of the back of the iron hosel. The breaks in the outer layer of the iron expose the metal of the hosel’s inner layer, which is much thicker than the outer layer. According to Paul Thorne of Anacortes, Washington, the master blacksmith who viewed all these images, it is at this area on the hosel that the outer wrap, which is not perfectly fused to the inner wrap, is exceptionally thin and has corroded away in places.

Above right is a radiograph of the hosel on its side, with its leading side facing the viewer. What looks like an oblong white hole are the holes on the lead and following side of the hosel, where the hosel is pinned/nailed to the shaft. According to Thorne, what appears in the X-ray as a crack in the top of the hosel is the end of the wrap that encloses the hosel, not a crack. The outer, overlapping layer was not installed to repair a crack. The circumference of the hosel shows no evidence of any raised areas or sections which would occur if a piece of metal was added after the hosel was formed.

Since this hosel was formed essentially as a tube, providing an overlapping layer around half of it would have been a natural way to construct it, especially given the fact that the bottom of the hosel needed to have extra material to fit over the front and back of the blade in order to attach it. Hosels on one-piece heads would not need such a long overlap.

No other known irons show evidence of a second layer.

The entire length of the back of the hosel shown above contains significant corrosion. As mentioned earlier, this deterioration occurred because the outer layer of the iron was thin and not perfectly fused to the layer of iron underneath it, which is visible down in the cracks.

Wrought iron typically contains impurities, such as slag inclusions, that can break down under prolonged exposure to the elements. Over centuries, this can cause deterioration in places. However, wrought iron is generally more resistant to corrosion than forged steel. Steel, especially when unprotected, tends to rust more quickly and extensively. This explains why this wrought iron head is still in such excellent condition. The oxidation on its surface is a very thin coat that serves as a naturally occurring protective layer for the metal underneath. This layer can be quickly ground off, revealing bright and shiny metal similar to steel. Although doing that to any antique golf club would be a travesty.

1.6eBlack Wood ↩

On the left is a portion of a rake head displayed in the British Museum. It has a wrought iron prong that extends through the remains of the original wooden rake head shown across the top of the image. Both the remaining wood of the rake head and the shaft in the iron head were broken centuries ago. They are now black, the result of being exposed to weather across multiple centuries before they were discovered.

The British Museum refers to this broken portion of a rake head discovered in Northamptonshire as follows: “Part of the oak beam and three iron prongs from what was probably a six or seven prong hay rake. Rakes became an essential part of farm equipment when the Roman introduction of the scythe greatly increased the quantity of hay that could be harvested.” The Roman occupation of England began in 43 AD and lasted until approximately 410 AD. This object, while undated by the museum, was part of a display of wrought iron from the first through fourth centuries found in England.

The black wood in both examples above is the natural result of being left out in the weather over many years. Due to such factors as moisture absorption, fungal growth, UV exposure, oxidation, and dirt accumulation, various physical, chemical, and biological processes occurred as the wood interacted with its environment. These processes altered the wood’s composition and appearance, leading to the development of dark pigments and a characteristic blackened patina as well as decay. As witnessed by their condition, both of these artifacts had been lost to the outdoors for an extremely long time.

Fortunately, as touched on in the prior section, wrought iron holds up exceedingly well to weather. It develops a stable, protective layer of rust—a dark/black patina—that protects the underlying metal from further corrosion. Forged steel, on the other hand, rusts more rapidly and extensively than wrought iron. The rust is often less stable and more prone to flaking off, which can expose fresh metal to further corrosion.

1.6fPeened Face ↩

During the 1500s and 1600s, blacksmiths would sometimes use peening hammers to increase the hardness and strength of wrought iron, to make it more durable for tools, weapons, and other functional items. Peening also allowed the blacksmith to control the shape and curvature of metal pieces and form designs.

The blacksmith who made this wrought iron head did not leave the face unfinished. He completed the face by pounding it with a peening hammer. I have never seen another iron with such deep peening. Peening marks, neatly rounded on their bottom and of relatively uniform size with raised edges, are nowhere else on this head, even on the back of the blade, where there is a bit more oxidation. And that difference makes sense.

When wrought iron is peened, it compresses the surface layer of the metal. This process reduces surface irregularities where moisture and corrosive agents like oxygen and salt could settle, potentially slowing oxidation. As the patina forms across the surface of the iron, if the surface is compressed and uniform due to peening, this patina or protective layer of oxides may adhere more tightly and uniformly, also providing better protection against further oxidation. Furthermore, wrought iron contains silicate slag that can influence its corrosion resistance. If peening causes slag to migrate to the surface and fuse into the protective oxide layer, it could further slow oxidation. In short, there are a number of reasons that would explain why the peened face is not as corroded as the back of the head, which does not show evidence of peening.

The oldest known irons typically have smooth faces, but a few have evidence of what could be light peening or corrosion. None, however, have a face with a good portion that appears deeply peened on relatively clean metal like the oldest iron. Sometimes their faces are slightly uneven from hammer marks left from when they were forged. Hammer or forging marks, however, are different from peening marks, where the face is given an extra step and hammered with a peening hammer. Moving from peened faces to smooth-finished faces would have been an evolutionary change, not simply a difference in makers.

1.6gRough-Finished Blade End & Topline ↩

Above left is the toe of the oldest iron. The very end of the toe is somewhat unfinished, neither smooth nor even, unlike all the other irons shown earlier in this report. This unevenness could be due to the blacksmith being in a rush or not mindful of details. Alternatively, such imperfections might have been considered acceptable when irons were first made.

Above right is the end of a Troon wood, where the rounded back of the head and the flat splay toe intersect. Similar to the oldest iron, the rounded end of the head is neither smooth nor even. It also shows file marks and multiple beveled areas instead of a nicely smoothed surface. The ends of the other Troon woods exhibit similar rough-finished surfaces. These unrefined elements on ancient clubs are evidence of their great age, not poor workmanship. What was once acceptable would change with time. The finer points of clubmaking and workmanship that earlier clubmakers focused on were different from those of later clubmakers.

For example, the end of the blade as shown clearly demonstrates the blacksmith’s meticulous effort to taper the blade from the bottom to the top, just like it is on all the other oldest irons with curved blades. Additionally, as shown below, he skillfully tapered the top of the blade, making it thicker at the heel and narrowing to a point at the toe. This taper is the most gradual of all topline tapers I have encountered.

Achieving these tapers required a high level of skill. The smith did not create these tapers just to do it. They were forged to meet what I believe was the established standard at the time. As shown below, there is a beautifully executed symmetry between the taper of the top line and the taper of the toe.

According to master blacksmith Paul Thorne, to create a taper in two different directions, the smith began with a rough forging of uniform thickness. During the detailed forging, he would pound the back edge to make the blade thinner. However, as the back edge was thinned, it would grow longer and naturally tend to curl. The smith had to obviate that and straighten the curl while still keeping the tapered form in place in both directions. When accomplishing the above, he also needed to keep the thickness of the blade even across the entire length of the sole, which he did. Again, to create such a blade required no small amount of expertise.

Top-to-bottom tapering is less prominent and sometimes eliminated in the round-toe irons of the mid and late 1700s as can be seen in section 1.5. Heel-to-toe tapering along the top of the blade is the rarest form of tapering. It’s only on some of the earliest irons, and when found the taper is almost never as long as it is on the oldest iron. Note that the drawing of the 1682 iron in section 1.4 shows a much longer heel-to-toe top-line taper than is found on later square-toe irons.

The fact that the hosel weld on this head is not visible, that the smith took the time to blend it in nicely, provides additional evidence that the blacksmith was doing good work. On many irons made during the featherball era, evidence of the hosel seam is on full display.

Also, the topline of the oldest iron, as shown below, is not as refined as it is on the other irons in this report including the Troon irons. Even so, its construction from two pieces of metal with a laminated blade that is fully tapered in two directions goes beyond any other known ancient iron. The blacksmith behind this clubhead was undoubtedly skilled, but he worked in an era where the meticulous finishing of golf clubs had not yet gained widespread appreciation.

1.7Counter Perspectives ↩

Anytime a new antique club shows up on the market, especially one that appears really old like this club, the possibility of it being a fake or counterfeit must be considered in depth and at length. When the collector who acquired this club in 2001 showed it to me, I told him I was not sure when it was made. If I were to ever authenticate it or reject it, I would need to study it. Passing judgment on any antique golf club is something I take seriously.

For over two decades I have examined this club every time I was given the opportunity. For well over ten years I considered alternate origins. I would try to find evidence that it was modern. After all, there are rusted counterfeit square toe irons out there as I have documented on many prior occasions including a 63-page concluding chapter on replicas and fakes in The Clubmakers Art: Antique Golf Clubs and Their History; Second Edition, Volume 2.

Finally, it became clear to me that the only logical explanation for its existence is this iron is genuine—and it predates what was widely accepted as the oldest known irons.

I can now report that there is not one shred of evidence that indicates this clubhead is a fake. Instead, everything about it is beyond the realm of the counterfeiter. It is made from wrought iron—as its color, patina, laminated blade, and X-ray show. It is not made from mild carbon steel, the material of choice for constructing modern fakes and replicas given that wrought iron has not been commercially available for over a century. Furthermore, the construction of this head is far more complex and beyond the realm of what would be made in modern times if someone wanted to produce a counterfeit or replica square toe iron. On this iron, the evidence of great age in its every aspect is impeccably authentic.

Therefore, there are just a few ways that the unique features of this club can be explained. Either an inexperienced blacksmith centuries ago was just making an iron club head but didn’t really know what he was doing or was experimenting outside the standard construction methods of his day, or the blacksmith knew exactly what he was doing and made this head to match other irons made during his era.

Because I have never seen another early square-toe iron made by a blacksmith who was just winging it, blindly or otherwise, I believe this head is fully and acceptably formed for the era in which it was made, just like all the other square toe and spur toe irons presented above.

1.8Oldest Iron Conclusion ↩

The head is made from two pieces; it has a layered hosel that wraps halfway again around itself; the blade is laminated, its construction consistent with the ancient methods used to make Damascus steel; and its face is covered with deep peening marks. These are four features not one of which is found on any other existing iron made during the feather ball era that I know of. All the structural differences between this club and the nine previously recognized oldest irons indicate that this club was made before all of them.

The sweep of the blade up into the hosel that is found on all nine of the other oldest irons is not found on this club. Unlike those nine irons, the head of this iron is made from two pieces. But it is precisely because it is made from two pieces that it does not have a topline that sweeps up into the neck.

The graceful sweep up into the hosel on the other nine ancient irons is a refined element when compared to the two-piece connection between the hosel and blade on this iron. Such a structural change from a two-piece iron head to a one-piece head would be a watershed event in golf club evolution if that is actually what happened. It would also explain where the sweep in the neck found on all nine of the other ancient irons evolved from if one-piece iron heads were not there at the start. But if one-piece iron heads were there, as they most likely were, the demise of two-piece heads that coexisted with one-piece heads was an evolutionary dead-end. Either way, this club is a monumental find.

Adding to the evidence that this iron head is the oldest known is the fact that the walls of its hosel are clearly thicker than they are on the other nine irons. Because of that, the shaft is not as thick, nor was it originally, as the shafts in the other nine. It is not surprising that it broke.

The simplest explanation for all the differences between this iron and the other nine ancient irons documented earlier is that this iron is older than those irons. That is what the evidence indicates. That is what the club is telling us. That is what the club itself tells the world. This is why I firmly believe that this long lost relic could easily be the oldest iron/golf club in existence. Nothing else currently known begins to compare.

Long-Nose Woods

2.1Troon Clubs - Early 1600s ↩

Dating antique clubs can present unique challenges. Since clubs were handcrafted by different blacksmiths and clubmakers and not mass produced until the late 19th century, it’s helpful to consider important historical context clues as well as have a firm understanding of clubmaking evolution to get an accurate idea of a club’s age. To illustrate this process, I will begin by presenting the Troon clubs, previously thought by many to be the oldest antique clubs in the world. I will then share the fundamental aspects of the evolution of long nose woods across three centuries, from the 1600s into the 1800s.

The six woods and two irons shown above comprise what are often referred to as the Troon clubs. They are the oldest known set of clubs and were lost to the world for over a century and a half before being discovered in 1898 and then gifted by Adam Wood to the Royal Troon Golf Club. These clubs remained on display there for nearly a century. They now reside at the R&A World Golf Museum in St. Andrews, Scotland.

The clubs were discovered in a boarded-up cupboard/closet during the remodeling of a home—the Maister house—in Hull, England. They were most likely boarded up during or shortly after 1741, as a newspaper of this date was found with the clubs. After the clubs were found, The Times ran a detailed article, reprinted in the August 26, 1898, issue of Golf, that stated these eight clubs were “by far the oldest extant implements for the practice of Golf, as well as being without doubt the most ancient relics connected with the game. The clubs themselves bear the impress of great age....” The article continues that “Mr. Balfour, the Leader of the House of Commons, has seen the clubs, and gives it as his opinion that they may belong to the period of the Stuart Kings.” The article also refers to their abnormally large size, noting that the clubs are bigger with at least “twice as much wood as in the average club of the present day.”

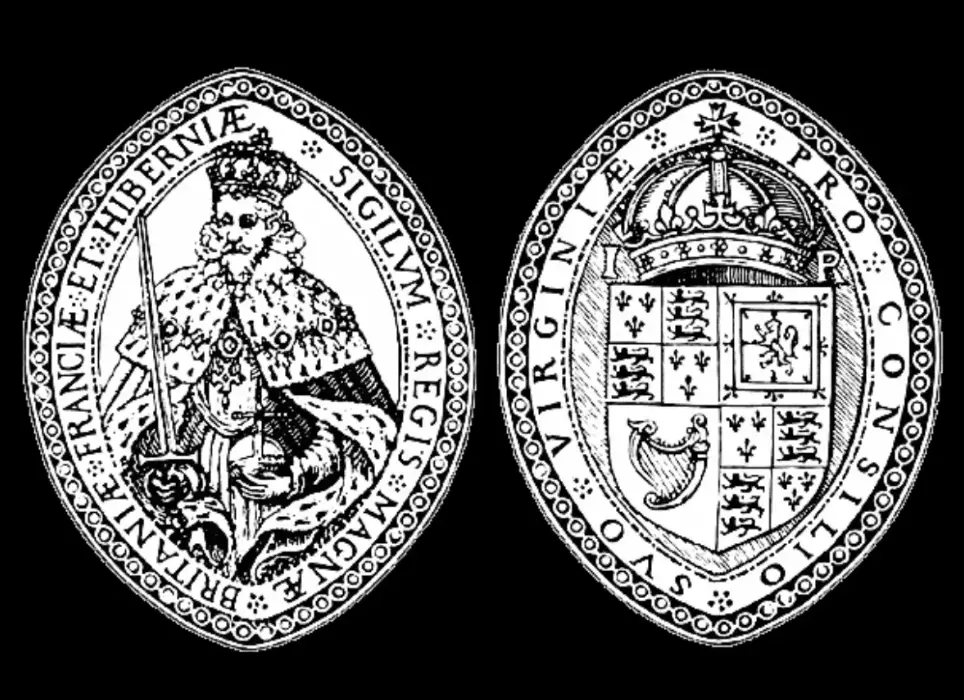

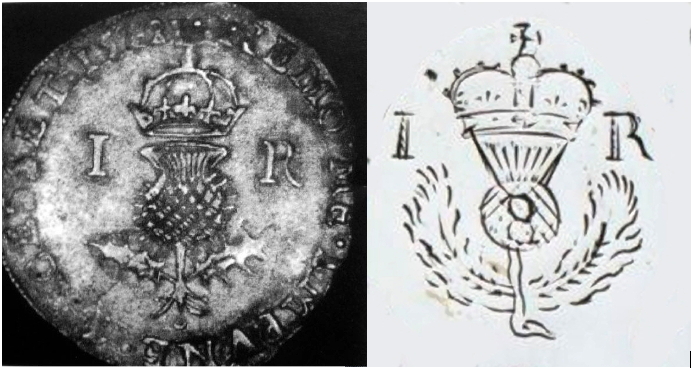

These eight clubs—consisting of three play clubs, three spoons, and two irons—were obviously very important when they were made. They are marked a total of forty-four times with a stamp that includes the King’s crown above a thistle (the symbol of Scotland), the letters I and C, and a star. The crowned thistle bordered by a single initial on each side matches the layout of multiple King James VI of Scotland (James I of England) coins. The only difference is the “C” on the clubs is an “R” on the coins and the coins do not use a star.

A close examination of James VI/I coins provides further insight into the historical significance of the Troon clubs. In an article published in the June 20, 2010 issue of Through the Green (pp. 41-43), Ian Crowe presents an image of a James VI/I coin, shown above, that closely resembles both the layout and style of the marks found on the Troon clubs. Crowe concludes that these clubs were likely owned by James VI/I, and that William Mayne, appointed Royal Clubmaker to James VI/I in 1603, likely made them for him in the early 1600s. (In 1603, Mayne was also appointed as the King’s bower, fledger, and “speir-maker.” As a bow and arrow maker, Mayne knew how to work with wood. As a spear maker, he knew how to work with metal. Mayne was well qualified to make both woods and irons.)

Above is the James VI/I coin alongside a Troon club with one of its stamps darkened for publication in 1898. (Note that the faint original stamps are more symmetrical than the single darkened stamp.) The “I” and “R” on the coin represent “Iacobus” and “Rex,” Latin for James and King. According to Crowe, the “C” on the club identifies Charles who was born in 1600 and assumed the throne as King Charles I in 1625. Crowe documents that the star in the center of the club shows succession in royalty, but it can represent other things such as divine guidance, honor, achievement, leadership, and prominence.

Given the striking similarities between the marks on the James VI/I coin and the marks on the club, the evidence is strong that King James VI/I and his son Charles are directly connected to these clubs. Additionally, in 1637 King Charles I visited Hull, where these clubs were found.

2.1aKing James VI/I Coins & Clubs ↩

Because Crowe relied heavily on the dating of Stuart-era coins in dating the Troon clubs, I felt the James VI/I coins deserved a closer look. The crown over the thistle or “crowned thistle” is symbolic of the Scottish monarchy, especially the Stuart Kings. This crowned thistle is found on a variety of James VI/I coins minted during his reign (1567- 1625).

As shown below, James VI/I also included the I and R on other coins that had a crowned thistle. This layout of a crown above the Latin initial of the king and his title is a royal cypher. The particular layout and style of the symbols including the thistle on these coins are what make this royal cypher unique to James VI/I.

The above coins are not an exhaustive study. They are the results of a few hours of digging around on the Internet. But there is more to be noted from these coins.

Like his father, James VI/I, King Charles I minted coins including some that included a crown above a thistle as these four 20 pence coins made between 1625 and 1649 demonstrate. While I found King Charles I coins marked with a “C” and “R” none were on a coin as part of a royal cypher with a crowned thistle.

The only other ancient Scottish coin I encountered with a crowned thistle bordered on each side by a single character was a 1 Bawbee made in 1538 during the reign of James V, the Father of James VI/I.

Through my study of Scottish and English coinage,3 I confirm that Crowe was correct when he wrote, “James VI was the most consistent in using the thistle and the crown together and also, in his case, in using the letters I (Iacobus) on the left and R (Rex) on the right.”

My search confirmed that the coin Crowe used to date the Troon clubs is a valid key. There is no question the marks on the Troon clubs connect the clubs to Scottish royalty. Based solely on the similarities between the marks on the clubs and coin, the clubs could easily connect to the man behind the same marks on the coins—King James VI/I.

The “C” on the clubs could be to acknowledge the birth of Charles, heir to the throne of James VI/I. As I see it, however, the most logical reason for the “C” is because King James had the clubs made for his son Prince Charles at some point prior to 1625, when the prince became King Charles I at age 25. Many a father has provided their son with one or more sets of clubs. (Mine did when I was 12, 15, and 18.) After all, it was James VI/I who appointed a royal clubmaker who, indeed, is documented as having made clubs for his king.

2.1bDiscovery of the Clubs in Hull, England ↩

History also connects to the above analysis with precision. As mentioned earlier, the clubs were discovered in 1898 in Hull, England. They were found in a boarded-up cupboard during the renovation of the Maister house, which had been rebuilt after it suffered grave damage in a fire in 1743. As Phillip Boulton documents in his December 2010 Through the Green “Maister House” article, King Charles I was in Hull, England in 1637, 12 years after he was made king. When Charles I visited, he attended a reception a mere 300 yards from the Maister house. William Maister was a prominent citizen of Hull—a chamberlain in 1637, sheriff in 1645, and mayor in 1655—and most likely was at the reception. It would have been natural for Maister to provide his home for a few of the King’s dignitaries or soldiers to spend the night.

However the clubs came into the possession of the Maister family, be it as a gift or abandoned in haste, they would have been highly valued and never discarded. It is therefore understandable that a family living in England during the height of the Jacobite rebellion, which culminated with the battles of 1745 and 1746, might choose to hide the clubs of a Stuart King. With Scottish loyalists fighting England to restore the House of Stuart to the Scottish throne, displaying or even possessing golf clubs bearing a former Stuart king’s monogram could have marked the household as Jacobite sympathizers—an accusation that could have had serious consequences if reported.

2.1cSecond Possibility ↩

The marks found on the Troon clubs could also be those of a clubmaker to King Charles II. As Neil S. Millar reports in his book Early Golf (p107-108), in a document dated August 6, 1663, James Carstairs is listed as “Goffe Clubmaker” to King Charles II. Charles II is listed as having a clubmaker every year during the last 15 years of his reign (1660-1694) and likely had one the entire time. Many years his clubmaker is not named, but for the last two years David Gastiers was his man, although “Gastiers” may be a misspelling of “Carstairs.”

Therefore, the IC on the Troon clubs could be the initials of “James (Iacobus in Latin) Carstairs” clubmaker to King Charles II, and the Stuart thistle acknowledging his position as clubmaker to the king. If so, this would date the clubs to no later than 1671 given that Charles II visited Hull, England, in 1671.

If these are the marks of the maker, however, one is left to wonder why the marks are so involved, with a star inside an oval that also contains the Stuart thistle and two initials. And why so many marks? Marking each club six times and each iron shaft 4 times indicates that the clubs were made for somebody special, and if Carstairs made them for a king, then why would the stamp not include the initials “C” and “R” to identify the king? Furthermore, the fact that these clubs were found stored in a boarded-up closet, showing little to no use, indicates that, to their owner, they were more than simply clubs made by a prominent clubmaker.

Another major stumbling block to attributing the "I" and "C" marks on the clubs to James Carstairs is this: Would a servant named James use the letter "I" to abbreviate his name? The most likely answer is that he would not. The use of "I" in place of "J" is specific to the Latinized form of the name Jacobus or Iacobus which was traditionally reserved for royalty or formal use in official inscriptions, especially on coins.

The answer to all of this is found in re-examining the oval shape—what historians have long called the rhombus or lozenge shape—that contains the Stuart thistle, heraldic star, and initials. By definition, a rhombus is a quadrilateral with four equal sides. Its opposite sides are parallel, and opposite angles are equal. Ian stated that the rhombus as marked on the Troon clubs was “a token of noble birth.” In my research into Scottish heraldry during the 1600s, I found that when a rhombus displays the arms of a noble family, it indirectly signifies the bearer’s noble lineage. So given the Stuart thistle inside the lozenge, it could acknowledge nobility. However, the rhombus was primarily used in heraldry to display the arms of unmarried women and widows.

2.1dHeraldry and Iconography Provide the Answer ↩

Upon re-evaluating the marks on the club heads, I began to doubt whether describing them as rhombus-shaped accurately captured their oval appearance, observed on 44 instances across these 8 clubs. The August 26, 1898 issue of Golf magazine characterizes the marks as resembling either a "rhombus with rounded obtuse angles, or an an ellipse with the ends run to a point [italics mine].”

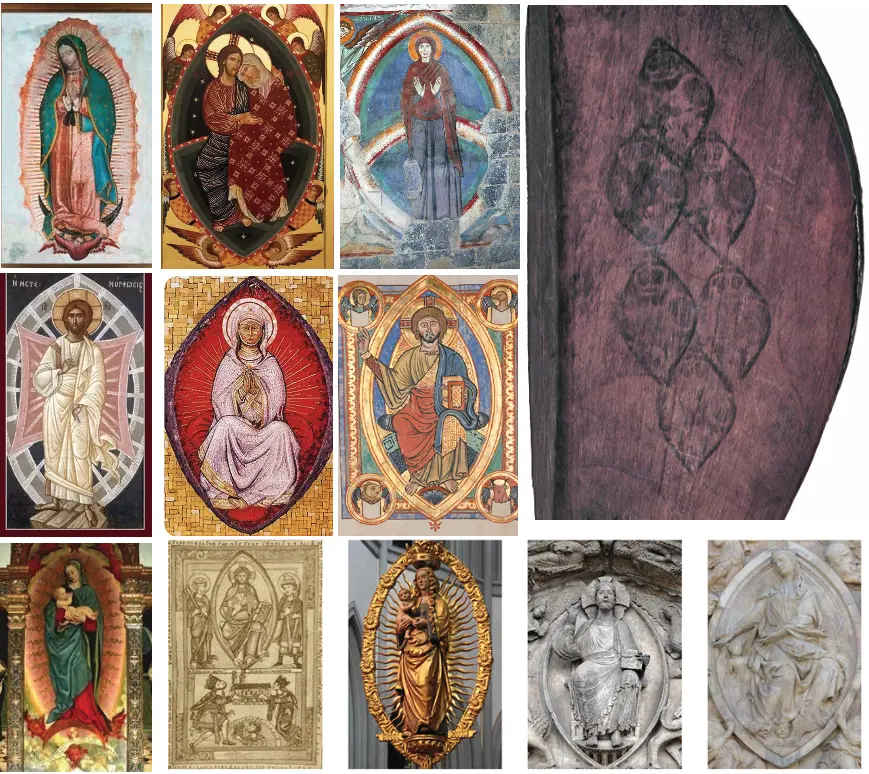

The description “an ellipse with the ends run to a point” is one way to define a vesica piscis, a shape that can also be characterized as a pointed oval, typically formed by the intersection of two arcs.

The vesica piscis shape was used in Christian iconography for over a thousand years prior to the reign of James VI/I. It often frames images of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and other saints, symbolizing holiness and the intersection of heaven and earth. The vesica piscis is a common motif in Gothic architecture, appearing in the design of windows, doorways, and other structural elements. Below are a few examples shown next to the stamps on one of the Troon woods—their connection is readily seen.

James VI/I was a deeply religious man. He was raised a Protestant, and his faith deeply influenced his personal beliefs and political actions. He tried to unify England and Scotland under Protestantism and sought to maintain peace in doing so. Lest we forget, it was James VI/I who in 1604 commissioned the translation of the best Greek and Hebrew manuscripts of the time to produce what is now known as the King James Bible, first published in 1611.

James VI/I was also a strong proponent of the divine right of kings, believing that monarchs (such as himself) were appointed by and answerable only to God. In his political treatise “The True Law of Free Monarchies and Basilikon Doron” first published in 1598 (and last published in 1994), James sets forth the doctrine of the divine right of kings and of the king’s responsibility to God alone. Undoubtedly, he was well aware of the symbolism and use of the vesica piscis in architecture and Christian art.

During a recent visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, I found a dozen examples of the vesica piscis in Christian art in just a few minutes. Below are three images of the vesica piscis symbols on view at the Met. These examples document that others, not just Christ and Mary, were used as the focus subject. I found it especially notable that one of them framed a horseback rider described as “possessing all the poise of a great knight.”

From left to right below, according to the placards on display at the Met, these three vesica piscis symbols were used on:

- “Fragment. Bust of the Archangel Michael;”

- “Equestrian Plaque. Sure-seated rider, possessing all the poise of a great knight. Identity unknown. His bearing has much in common with the kings on horseback from the sacred story depicted in stained glass exhibit Scenes from the Legend of St. Vincent...;”

- “Tabernacle of Cherves...Doubting Thomas.”

While the use of the vesica piscis in Christian art had begun to wane by 1600, the meaning behind it—the intersection of the divine with the human—did not change. The general populace may not have had a strong understanding of the vesica piscis, but many educated individuals, part layout is reminiscent of thaticularly those with an interest in art, history, or theology, would have recognized its significance.

In 1606, King James actually created a coat of arms where his image is framed by a vesica piscis, as shown below:

This coat of arms was created to serve as the seal for the Charter of the Virginia Company of London, established by royal charter of James VI/I on April 10, 1606, just three years after prince Charles was born. The purpose of the company was to establish colonial settlements in North America. It was responsible for establishing the Jamestown Settlement, the first permanent English settlement in the present United States in 1607.

As shown above, it was James VI/I who framed himself in a vesica piscis for all to see. Can there be any doubt left as to who it was that used a vesica piscis to frame the symbols on the clubs, symbols that for all intents and purposes match the royal cypher of King James VI/I as shown on some of his coins?

2.1eRoyal Cyphers and Insignia ↩

In its simplest form, a royal cypher consists of two stylized initials. The first initial is often the monarch’s Latin name, and the second is the monarch’s Latin title—R for Rex (King) or Regina (Queen). These initials are typically placed directly beneath or adjacent to a crown. Like other royal insignia, royal cyphers served as personal emblems of reigning monarchs, symbolizing their authority and presence on various items such as official documents, coins, uniforms, buildings, and more

Royal insignia, which can include royal cyphers, coats of arms, and other heraldic symbols, often incorporate elements used by previous monarchs. However, these shared elements are frequently redesigned, resized, and rearranged to create a distinct insignia or cypher for each new monarch. As a result, while there may be shared symbols, the overall appearance will be distinctly different, much like a signature, distinguishing one monarch’s reign from another.

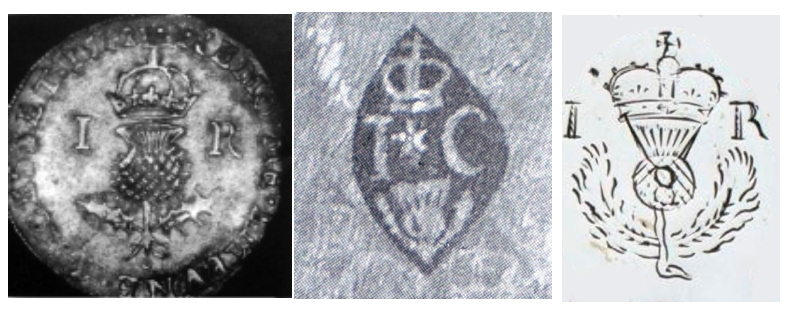

The fact that royal cyphers and insignia were made to distinguish one monarch from another is the key that unlocks the age of the Troon clubs. It also explains why the royal cyphers and insignia on the coins of the different monarchs just reviewed are distinctly different from one monarch to the next. Given the royal insignia of James VI/I and James VIII, anyone can compare them to the insignia on the Troon clubs and see for themselves which king is behind their creation.

The James VIII coins presented earlier in section 3.1a did not feature anything resembling a King James VIII cypher. However, James VIII did, in fact, have his own royal insignia that included a cypher. As shown below, it is engraved on a snuff mull gifted by James VIII to Colonel Donald Murchison in 1715. This insignia includes a crowned thistle bordered by the initials 'I' and 'R.'

Like James VI/I before him, James VIII used a crowned thistle as part of his royal insignia. Additionally, the James VI/I coin features the same initials as those found on the James VIII insignia, but that is where the similarities end.

The insignia in question are markedly different. The crown and thistle in the James VIII insignia come together to form a third heraldic symbol—a heart. This display of creative ingenuity sets the James VIII insignia apart from all others and uniquely identifies him as the monarch. While heraldic designs often carry layered meanings, the combination of traditional Scottish symbols, such as the thistle, with the heart shape could symbolize the monarch’s dedication and loyalty to Scotland.

As shown above, the heart shape is formed exclusively by the King James VIII insignia, whereas the Troon stamp insignia bears a much closer resemblance to the James VI/I design. Additionally, their basic royal cyphers—comprising the crowns and initials—differ significantly. The crowns on both the coin and the Troon stamp are formed nothing like the top half of a heart, unlike the crown found on the James VIII cypher.

The comparison of these three royal insignia, once again, points directly to James VI/I as the monarch behind the Troon clubs.

Note that the small size and vesica piscis shape of the Troon stamp, along with the likelihood that it was crafted by a clubmaker, limit the degree of detail it can display. However, the significance of royal cyphers and insignia doesn’t rest in the small details—which can sometimes resemble those of other monarchs—but in their overall composition and design. It is the complete presentation that makes each one unique and identifiable as belonging to the monarch who created it. With royal cyphers and insignia, “some of the flowers might look similar, but the gardens are entirely different.”

To review, the stamp used on the Troon clubs consists of a crown over a thistle, the letters “I” and “C” separated by a heraldic star, and a vesica piscis that encompasses all the other marks. In addition, each wood is stamped six times in such a way that it replicates the vesica piscis shape of the individual stamp. These marks are not simply decorations. The stamp was created as an insignia to identify the person who owned the clubs and to speak to any person who saw the clubs.

So, what does the stamp tell us? The crown represents the king and the thistle represents Scotland. The “I” stands for James in Latin, and the C stands for his son Charles, and the heraldic star between the letters shows succession—that Charles is the successor to the throne after James. The vesica piscis enclosing those symbols shows holiness or “divine approval” for James being the King of Scotland and Charles the heir. The stamps repeated six times in the form of a vesica piscis serves to emphasize the last point of divine approval/rights. It’s all very simple. James VI/I was the king, his son Prince Charles was his successor, and they both had a divine right to the throne.

Given that no clubmaker ever claimed a divine connection to their trade—and wisely so—these marks clearly belong to a king. Moreover, to link the initials "I" and "C" to James VIII or Bonnie Prince Charlie, born in 1720, would require overlooking key facts. The only royal insignia that matches the Troon stamp is that of King James VI/I, not James VIII. Additionally, James VI/I’s use of a vesica piscis to show his deep religious character on a coat of arms is the simplest explanation regarding why a vesica piscis was used on clubs marked with his initial and crown. Bonnie Prince Charlie, by contrast, has no discernible connection to Hull, England. He was born in Italy and lived most of his life in Europe, spending approximately just one month of his life in England, and that was during the Jacobite uprising in 1745. It was not the type of trip where you would bring your clubs.

Attaching the Troon clubs to King James VI/I is—by far—the most logical answer to who was the original owner of these clubs. The facts all line up. All the marks on the clubs—the letters and symbols, the use of the vesica piscis, the layout of six stamps to form a larger vesica piscis, the design of the royal insignia that matches the royal insignia on various James VI/I coins—connect to James VI/I without any need for speculation, uncertainty, or turning a blind eye.

The final question is why royal insignia were installed on golf clubs, of all things. Again, the answer is simple: The clubs were made for a king.

During the 17th century, craftsmen sometimes marked items made for a king with symbols that honored the king, and in many instances it was customary. They would do so under the direction and supervision of the monarchy. Items crafted for royalty often bore symbols, crests, or inscriptions reflecting loyalty and reverence. This practice was common across Europe and included various types of items from thrones to weaponry. Items associated with the monarchy typically featured heraldic symbols, such as the royal coat of arms, the king's initials, or other insignia representing the sovereign's authority and lineage. Craftsmen and artisans would often add inscriptions or engravings commemorating the king or specific events, underscoring their allegiance and the item's connection to the royal household. For instance, items from ceremonial objects to furniture used in royal residences were sometimes marked with such symbols. Similarly, official documents and proclamations would be sealed with the royal coat of arms.

Honoring the king in this manner extended to everyday objects as well. Ceramic plates and bowls, tankards, goblets, silverware, jewelry, clothing and more were occasionally decorated with a royal insignia. The coinage made for kings is another example of everyday items bearing a royal insignia. Coins were subject to the king’s approval, but he did not design coins.

Additionally, in the evolution of golf clubs, the Troon clubs date back to the early 1600s, as will be demonstrated. Such huge wooden heads with dramatic splay toes do not date to the late 1730s or early 1740s, when Bonnie Prince Charlie would have been old enough to use full-size clubs and James McEwan was just 30 +/- years from entering the clubmaking business.

2.2Duke of York's "1682" Club ↩

Property of Royal Musselburgh, the blonde club above right, known as the “Duke of York’s club,” is documented as having belonged to James VI/I’s grandson, the Duke of York who became King James VII of Scotland and II of England. The duke gave this club to Andrew Dickson after Dickson served as the Duke’s fore-caddie in 1681-1682.

According to Dr. John McPherson, in Golf and Golfers Past and Present, published in 1891, “McEwan, the club-maker of Bruntsfield Links, has shown us a club which Andrew Dickson received from the Duke of York (afterwards James II). Andrew was the fore-caddie to his Highness at the links of Leith and a great favourite. He excelled in the art of making clubs and was considered better than William Mayne, the clubmaker to James I.”4

The Duke of York’s club was displayed at the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1901, and the exhibition catalogue states that Douglas McEwan gifted this club to Royal Musselburgh and “supplied all corroborative evidence of the Royal ownership” (p. 257).

The history of this club is documented by people who lived much closer to the time of its creation than we do today. While history is not always recorded accurately, I have nothing to present or propose that would challenge the established history of this club. The head is old, and its overall shape aligns with the stated period, slightly newer than the Troon clubs. Additionally, the provenance of the club, coming from the McEwan collection—which was small but focused on clubs made in 1800 or earlier—is significant. James McEwan was a clubmaker for approximately 17 years while John Dickson, a relative of Andrew Dickson and the last of the Dickson clubmakers, was working just a few miles away in Leith. If James McEwan was indeed the McEwan who acquired the duke’s club, which seems quite likely, he certainly would have been told about its connection to Andrew Dickson. Receiving a club from a duke who later became king is historically significant—something that would never be forgotten, but always revered.

The club does have a hickory shaft when ash would be expected, but clubs were often reshafted. This one was once owned by the long-lived McEwan clubmaking family, founded by James McEwan in 1770. Reshafting a club was easy work for him or any of his clubmaking posterity.

Both the Troon club shown above left and the Duke of York club shown above right have a slanted or “splay” toe, characterized by a relatively flat, angled surface between the toe of the face and the toe of the crown. The dramatically pointed splay toe on the Troon club is replaced with a flatter, less pointed splay toe on the Duke of York’s club as the evolution of the club works its way towards an entirely rounded toe. Outside of these two woods, I know of only four other ancient woods that have a splay toe: two that belong to the Earl of Wemyss and two of slightly more recent vintage owned by the R&A.

Over time, the splay toe became less prominent until it was replaced entirely by the round toe.

The size of the duke’s club from 1682 is hard to appreciate when shown next to the Troon club earlier. Both are extremely large with thick necks. It is not until an old long-nose club is shown next to a newer long-nose club that the differences in their sizes become apparent and the older club is revealed as being much larger—that it is made from a larger piece of wood.

Therefore, in the image above, two typical spoons made by Hugh Philp, who was making clubs between 1817 and 1856, are shown next to the Duke of York club. A number of features on the duke’s club show that it is much, much older than the Philp clubs. Not only does the duke’s club have a splay toe, but its head is dramatically longer and thereby much larger than the Philp heads. Its neck is thicker and elongated before the whipping, and the neck under the whipping is much thicker. In short, the Duke of York clubhead when compared to the Philp clubheads is a much larger piece of wood.

2.3James McEwan 1786 Spoon ↩

The duke’s club is made up of many elements that indicate its age, but the size and thickness of its neck are fundamental. Necks were not given to novel designs and strange shapes by early clubmakers. They are a constant element that was gradually downsized until the end of the feather ball era. This was a slow, relatively linear progression. The typical long-nose club made between the early and mid-19th century will have necks of a similar size. Yes, there can be some variation depending on whether the club was a play club, spoon, or putter, but such variations are small in the vast majority of instances. It was only when the feather ball era came to an end that clubmakers reversed direction. With the adoption of the gutty ball, clubmakers began to thicken and increase the size of the neck to make it more durable against the harder ball.

Bearing both James McEwan’s thistle stamp and “McEwan” name stamp, the spoon above left was once the property of the McEwan family. Because there is no question that this club was made by James McEwan, it stands as a benchmark club for the 1770-1800 period. The October 9, 1896, issue of Golf includes a picture of this club and states that Douglas McEwan, the grandson of James, wrote “James McEwan 1786” on its sole, which writing is still there to this day. The fact that this club is stamped with a Thistle dates it no later than 1800, when James McEwan, the only McEwan credited with stamping a thistle on his clubs, died.5 The club cannot date any earlier than 1770, as that is the earliest given date when James entered the clubmaking business. The 1786 date seems fair. It is a midpoint of possibilities especially given that it is not known when James started and stopped using the thistle, or how often he would apply the stamp to his work.

Above right is an unmarked spoon with a 43” shaft. Complete with knots in the wood atop its toe, this clubhead is distinctly older than the McEwan thistle spoon shown, which has a 41 1/2” shaft and notably more loft. The head on the unmarked spoon is wider, especially from the middle of the head back to the neck. Its neck is more elongated and thicker, and the head is half an inch longer than the McEwan. Furthermore, on the unmarked spoon the entire top of the head is more crowned, rounded from front to back, and the apex (furthest protruding area) of the rear of the head is at 9:00 while the McEwan is at 7:30. The back of its head is thinner, top to bottom, and its lead protrudes well beyond the wood. The 1735 spoon does not have a splay toe, but its toe is distinctly narrow and not as broad as the McEwan’s. There is more, but the differences listed combine to provide unequivocal evidence that the unmarked spoon is much older than the McEwan.

In its entirety, the c.1735 spoon has a completely different head shape that stands apart from any of the known Alexander Neilson (working 1772?-1787), James McEwan (working 1770-1800), and Cossar clubs (working 1775-18166) or any of the clubs made by the clubmakers that followed them. Clubs by these three makers are very similar and tell us what clubs looked like during the 1770s to the early 1800s. Clubmakers did not work in a vacuum. They knew what a good club looked like, what other makers were producing, and what their customers expected.7

2.4Evolution Basics ↩

The four clubs above show some of the basic fundamentals in the evolution of the size and shape of the oldest woods.

The Duke of York club to the far left has a splay toe that is not as pointed as that on the Troon clubs. The second club from the left has an elongated head, curved face, and thick neck that are much like those things on the Duke of York club. However, it does not have a splay toe. Instead, the area where the splay used to be is neatly rounded. The third club from the left has an even broader round toe. The circa 1840s Hugh Philp spoon to the far right has a rounded toe that is shorter on the face side because the face was given a great deal of loft.

It is extremely difficult to gauge the size of a long-nose club and its features when there is nothing to compare it to. The three clubs above to the right were all side by side for this image, so their size differences are obvious. Notice how the heads and the necks become progressively smaller when arriving at the c.1840s Philp. This club is a short spoon, so its head is about as wide and big as a Philp clubhead will be. Even so, it is still much smaller than the c.1735 spoon. While both might have the same dimension at their widest points from front to back, the 1735 spoon is much wider across the entire length of its head than the Philp club—its head being formed from a much larger piece of wood. Given the approximate 100-year span between the creation of these two clubs we get an idea of how much the size of the clubs changed in general during those 100 years. Comparing the Philp to the c.1700 spoon shows an even more dramatic difference in the head and neck size between the two clubs. 8

Notice the exceptionally elongated necks on the Duke of York and c.1700 spoon when compared to the c.1735 spoon and the c.1840 Philp. The thickness and length of the neck, the shape given to the toe, and the size of the head are all typical structural features that are part and parcel to the eras from which these clubs were made.

2.4aSpoon Evolution in Six Clubs ↩

From left to right are six spoons made between approximately 1750 and 1880: c1750 unmarked, c1770s McEwan, c1786 thistle-stamped McEwan, c1840 Hugh Philp, c1870 Tom Morris, c1880 George Forrester. These six clubs show how spoons continued to evolve smaller between 1750-1880.

- The circa 1750 spoon on the far left is not marked with a name, which is normal for the oldest clubs. It has the thickest neck and beefiest head of the group. Notice how much larger this clubhead is when compared to the c.1786 McEwan thistle-stamped spoon. It is clearly older.

- The c.1770s blonde McEwan has a bigger neck—thicker all the way up its length—and a bigger head than the 1786 McEwan to the right. There are large knots in the wood across the face. Knots were eventually seen as blemishes as clubmaking matured. The shaft is the most unrefined, asymmetrical shaft in a McEwan that the author has handled, with many flat spots up and down its length. This is evidence of great age. It is not known when James McEwan started marking his clubs with a thistle, but most likely he acquired a name stamp first. This club has the earliest McEwan stamp, and the serifs on the individual letters do not show wear.

- The 1786 McEwan spoon was also made by James McEwan. He worked from 1770-1800 according to the McEwan family history published in the October 9, 1896, issue of Golf. This club was one of nine clubs in the McEwan collection of old clubs shown in an image that accompanied the article. “James McEwan 1786” was written on the sole in ink by Douglas McEwan to show who made this club and when. This club also bears a 1901 Glasgow International Exhibition label on its shaft.

- The c.1840 Philp spoon has a relatively broad head approaching the 1786 McEwan next to it, but it has a much shallower/thinner head than is found on the three older clubs shown. This difference is apparent in the depth of their faces. It also has a slightly thinner neck. As big as the head looks from the top view, the head uses less wood than the older three clubs.

- The 1870 Morris shows that the neck and head on a c.1870 club is different from what was made earlier in the 19th century, but it is not a dramatic difference.

- The 1880 Forrester made at the end of the long nose era has a neck that is as large as many were 100 years earlier. With the widespread adoption of the solid gutta ball during the 1850s, clubmakers began making necks larger in an effort to make their clubs more durable.

The evolution of the long-nose clubhead took time. The necks of the Forrester, Morris, Philp, and 1786 McEwan shown are not all that much different, although the McEwan is the largest of the four. There is, however, a marked difference between the necks on those clubs and the necks on the 1770s McEwan and 1750 unmarked spoon.

2.4bPlay Club Evolution in Two Clubs ↩

On the left is a play club formerly the property of the Cowdray Park Golf Club located near Midhurst, England. To the right is a c1800 McEwan Play club with the early McEwan stamp.

Notice that the Cowdray Park club is not only bigger but also dramatically larger in the neck. Again, the big head and thick neck are evidence that this club is much older than the McEwan play club. Its round toe and head shape compare well to the c1735 spoon shown two images earlier, but its neck is much thicker all the way up, more like the c.1700 spoon shown two images earlier. This indicates that the club was likely made after the c.1700 spoon but before the c.1735 spoon. This club has a hickory shaft where ash would be expected. However, the shaft appears to be a replacement given that the whipping lacks its finishing coat of pitch as was normal.

2.4cPutter Evolution in Two Clubs ↩

Above, the right-handed c. 1860s McEwan Putter and the left-handed HG putter are approximately 150+ years apart in age, the left-handed putter dating to the early 1700s.

Currently, the oldest reference to a putter or “putting club” as it was termed is found in a letter dated 1690 (Chronicles of Golf p146). Consequently, we know putters were in use by that time. That same letter refers to clubs being stamped with the initials “G.M....as the tradesman’s proper signe for himselfe.”

This left-handed putter, stamped “H.G.” on the crown, possesses a number of features that date this club to the early 1700s, if not a little before. Chief among these features that include an extremely large head, thick neck, protruding lead, and nailed listing grip is the slight splay toe. It is not nearly as prominent as the splay toes on the Troon clubs or the Duke of York’s club discussed earlier, and it is not readily apparent when viewing the top of the head due to the wear along the edge of the crown. But the flat toe is there, visible on the end of the toe right around the corner of the end of the face as shown in the two images below. The fact that it is shorter and less prominent shows that the splay was on its way out when this club was made.

The dramatic splay toes on the Troon woods did not simply disappear from the world of clubmaking overnight. Instead, the splay was gradually reduced until the round toes took over. You can see this evolution occurring with the Duke of York’s club (which is not as old as the Troon clubs) having a less pointed toe than the Troon clubs, and here this putter (which is not as old as the Duke of York club) has an even less pointed toe than the Duke of York’s club.

In the two-putter image above, we again see the evolution of wood head clubs during the feather ball era. Like spoon and driver clubheads, putter heads slowly evolved from large to small, splay toe to round toe, and thicker neck to thinner neck—from being made with big pieces of wood to smaller and smaller pieces of wood.

2.4dPutter Evolution in Seven Clubs ↩

The image above shows the general evolution of the putter from roughly 1750 on the left to 1880 on the right. Club evolution took time, and this image shows the relative time it took for clubs to evolve in their size across approximately 130 years. From left to right, the clubs are as follows: