Counterfeits! Antique Golf Balls That Don't Fly

Copyright © Jeff Ellis, 2023

Copyright © Jeff Ellis, 2023

This article was researched and written by Jeff Ellis, author of And The Putter Went Ping ;

The Clubmakers Art: Antique Golf Clubs & Their History; and The Golf Club: The Good, The Beautiful &

The Creative. Click here for more about Jeff.

This article is best viewed on a larger screen.

The antique golf market has become fertile ground for the sale of counterfeit golf balls, and has been for upwards of 15 years or more. To my knowledge, nobody has addressed this issue, so I am presenting here the results of a ten-month study on the topic. My statements and conclusions throughout this report are mine alone. They represent how I personally see things. I invite and encourage others to study my findings themselves, study antique golf balls themselves, and make their own conclusions.

Antique golf ball collecting is big business. The more desirable examples are not inexpensive. The most valuable balls have sold for upwards of $10,000 to over $30,000 in days past. Unfortunately, given the amount of money involved, golf ball collecting has taken a turn for the worse. Case in point:

At the end of last year, a ball collector sent me his collection of approximately 200 balls. He said over 100 of them “were repainted.”

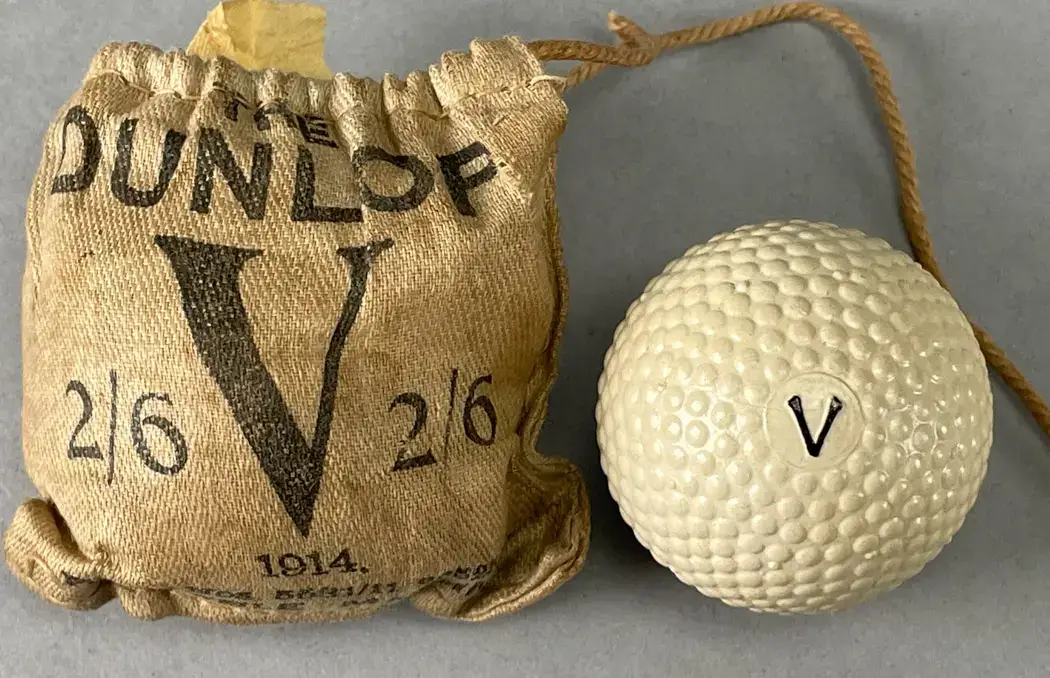

Repainted antique golf balls are not new to the hobby. During the late 19th century and early 20th century various ball manufacturers offered repainted balls, plus golf ball paint was offered in various golf catalogs for the do-it-yourselfer. Such balls are legitimate. During the late 20th century, as golf ball collecting came into prominence, antique balls were sometimes repainted to brighten up what might otherwise be seen as an unattractive dingy relic. Repainted golf balls have always been a part of the game and the collecting world, and of course, collectors always knew that bad things could lurk under the paint if it was too fresh. Even so, golf ball fraud was not seen as a big problem.

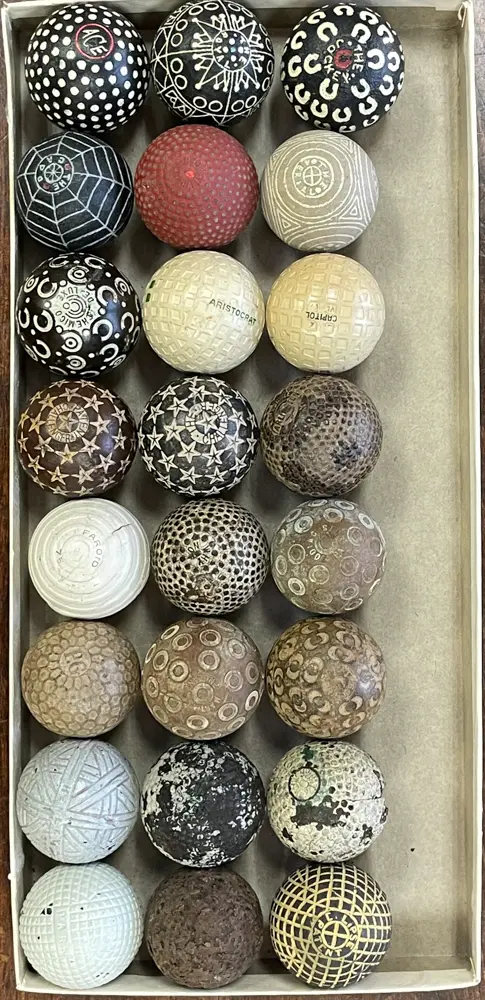

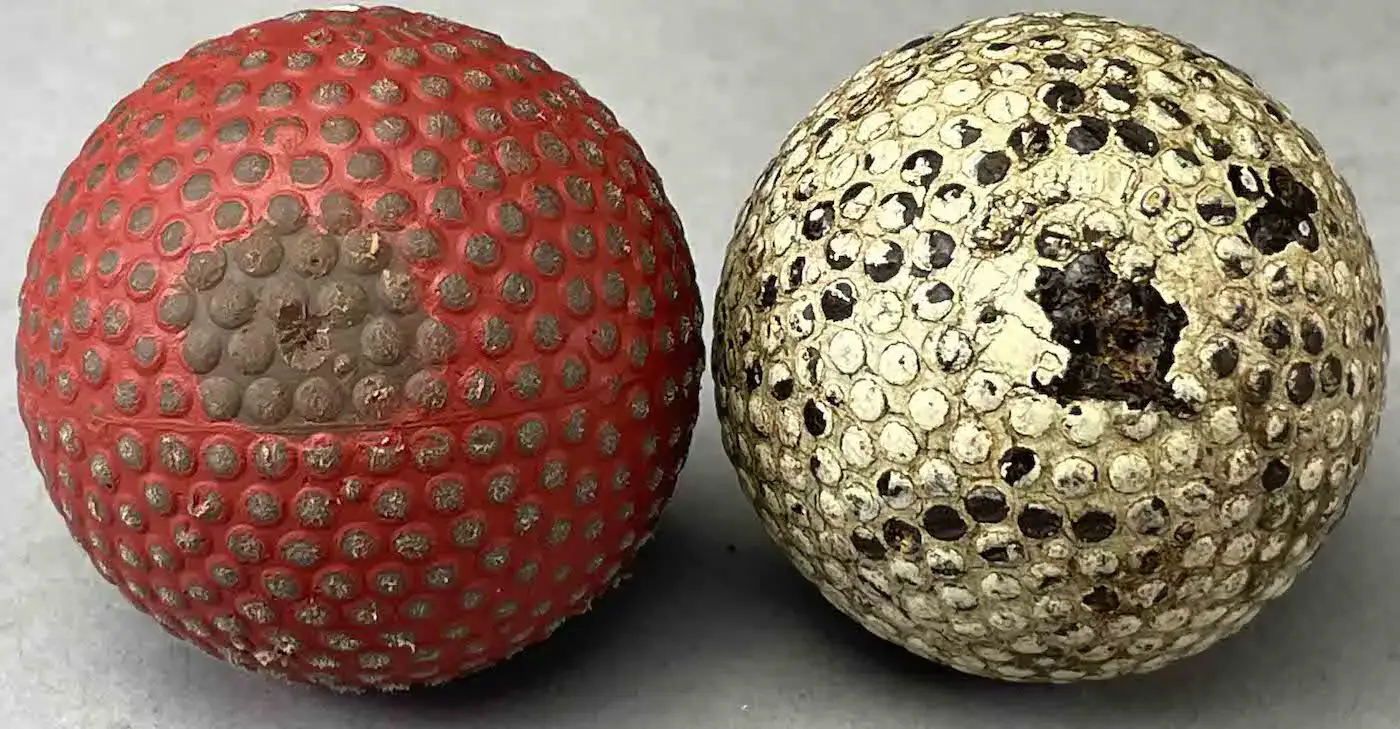

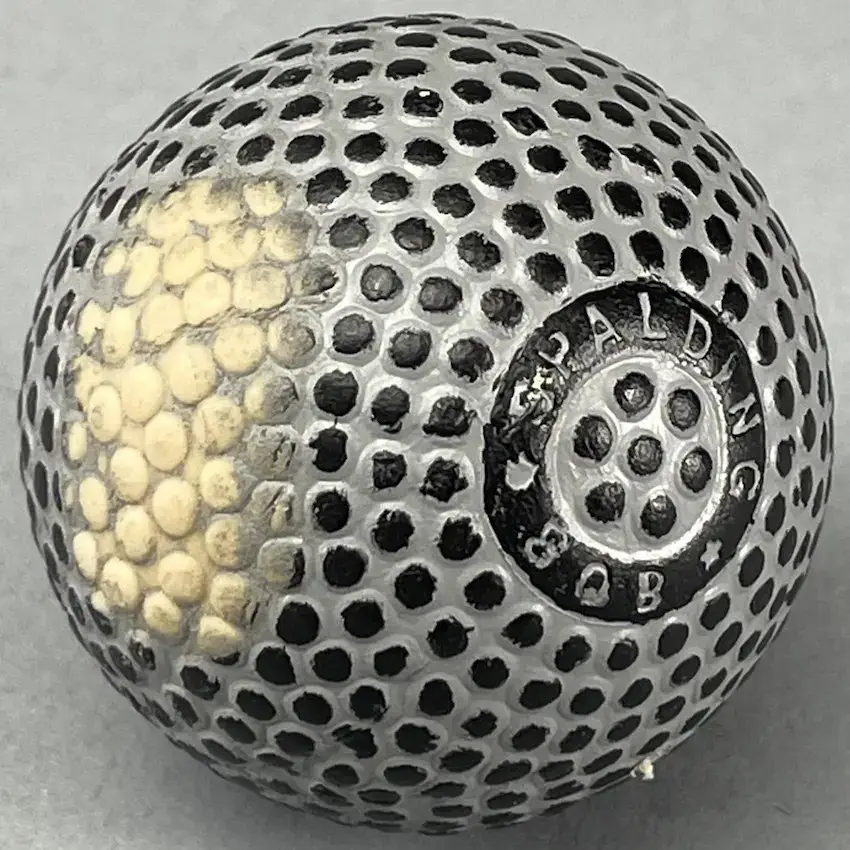

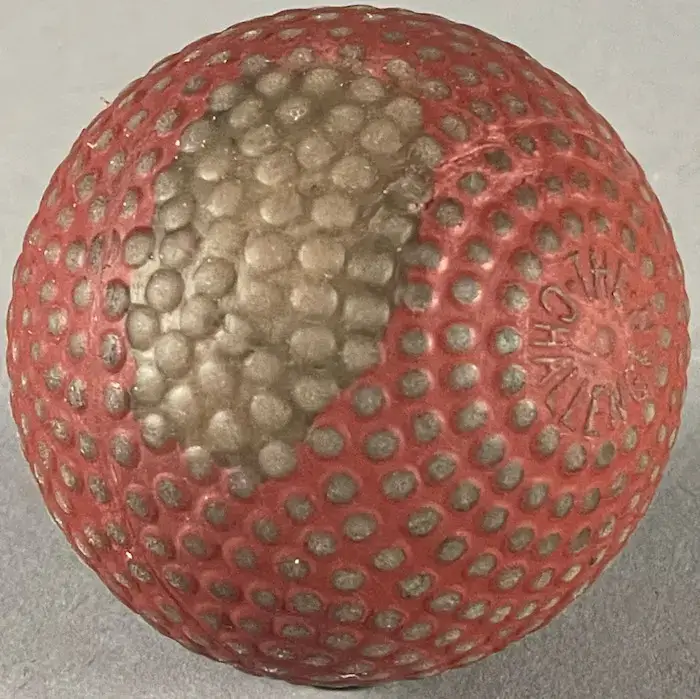

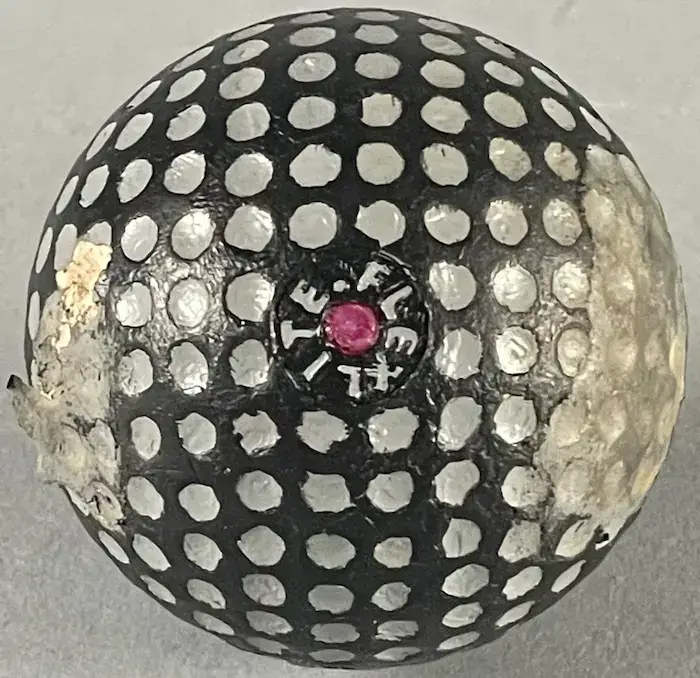

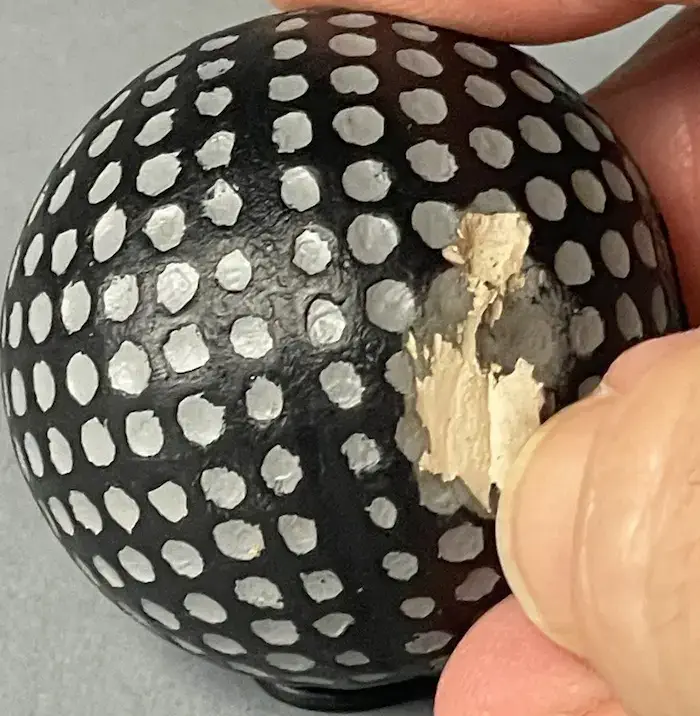

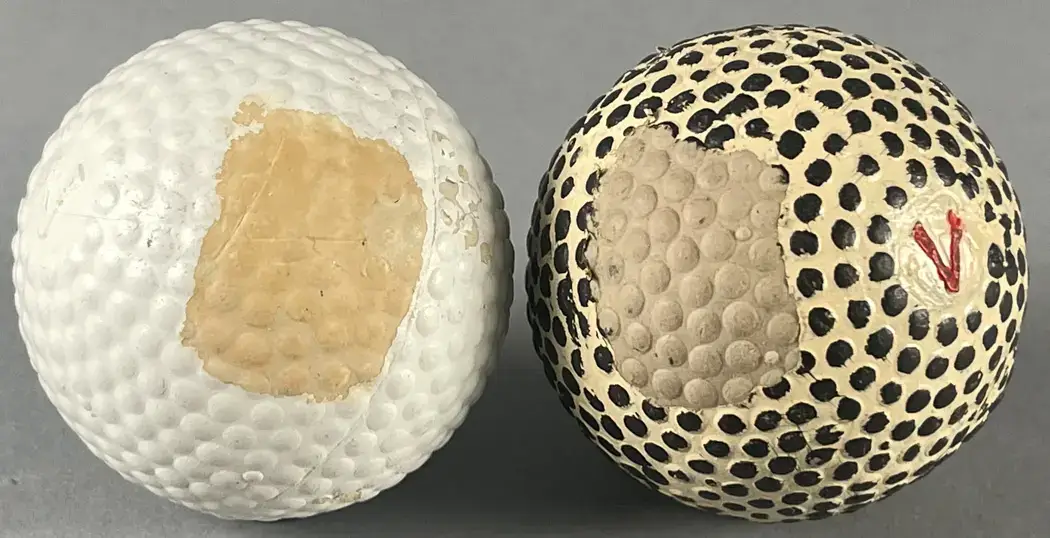

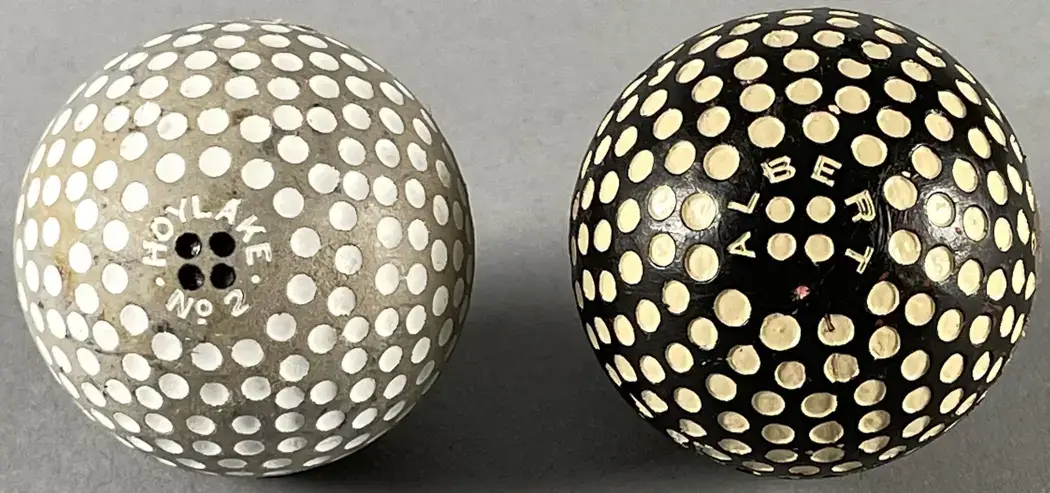

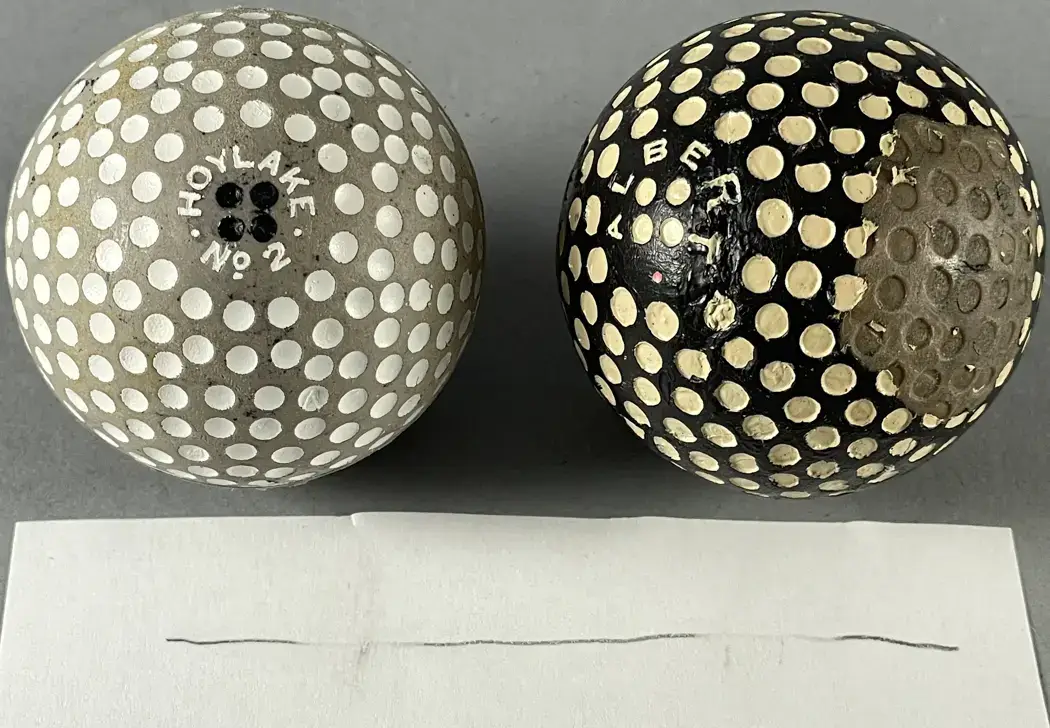

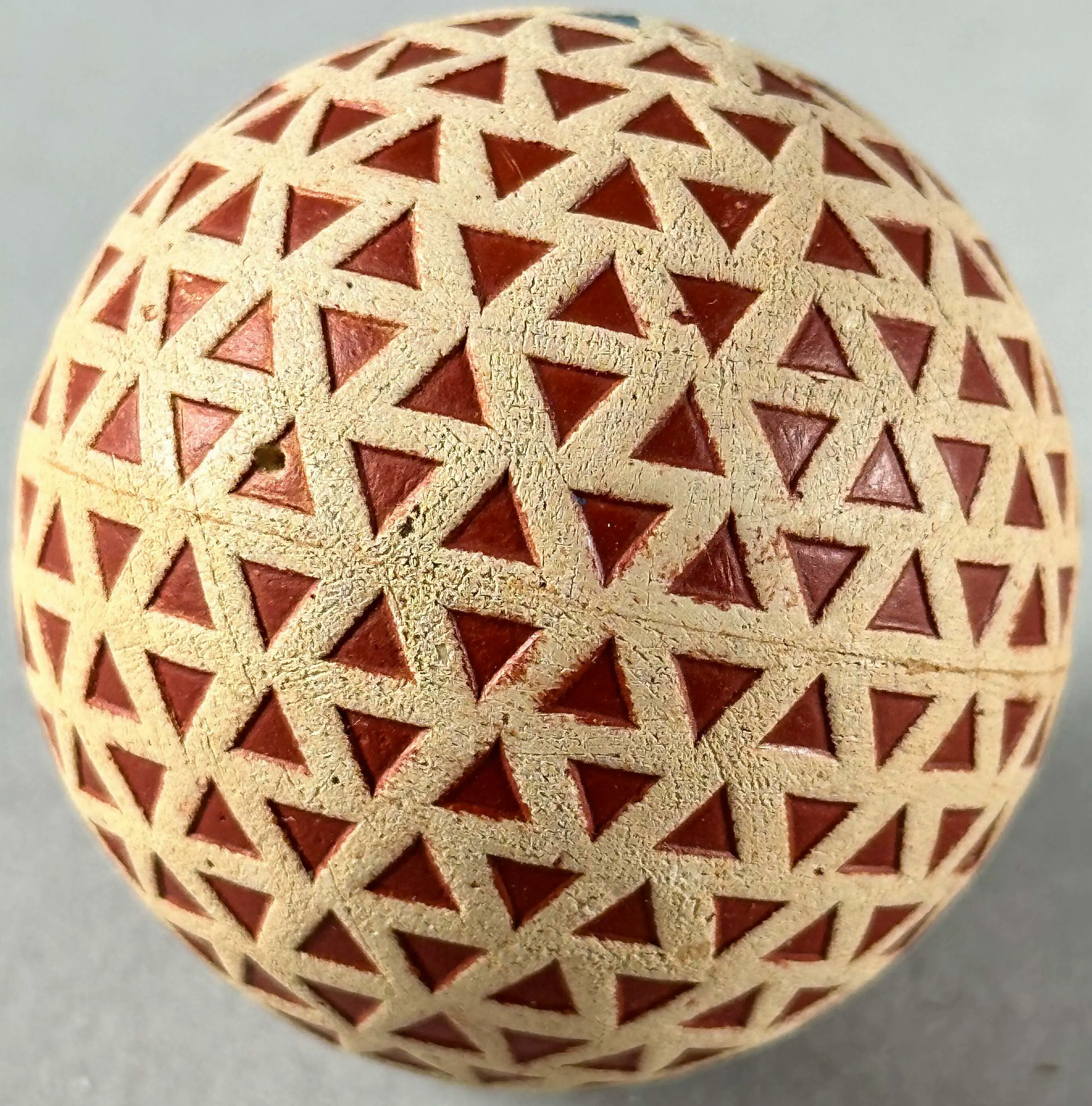

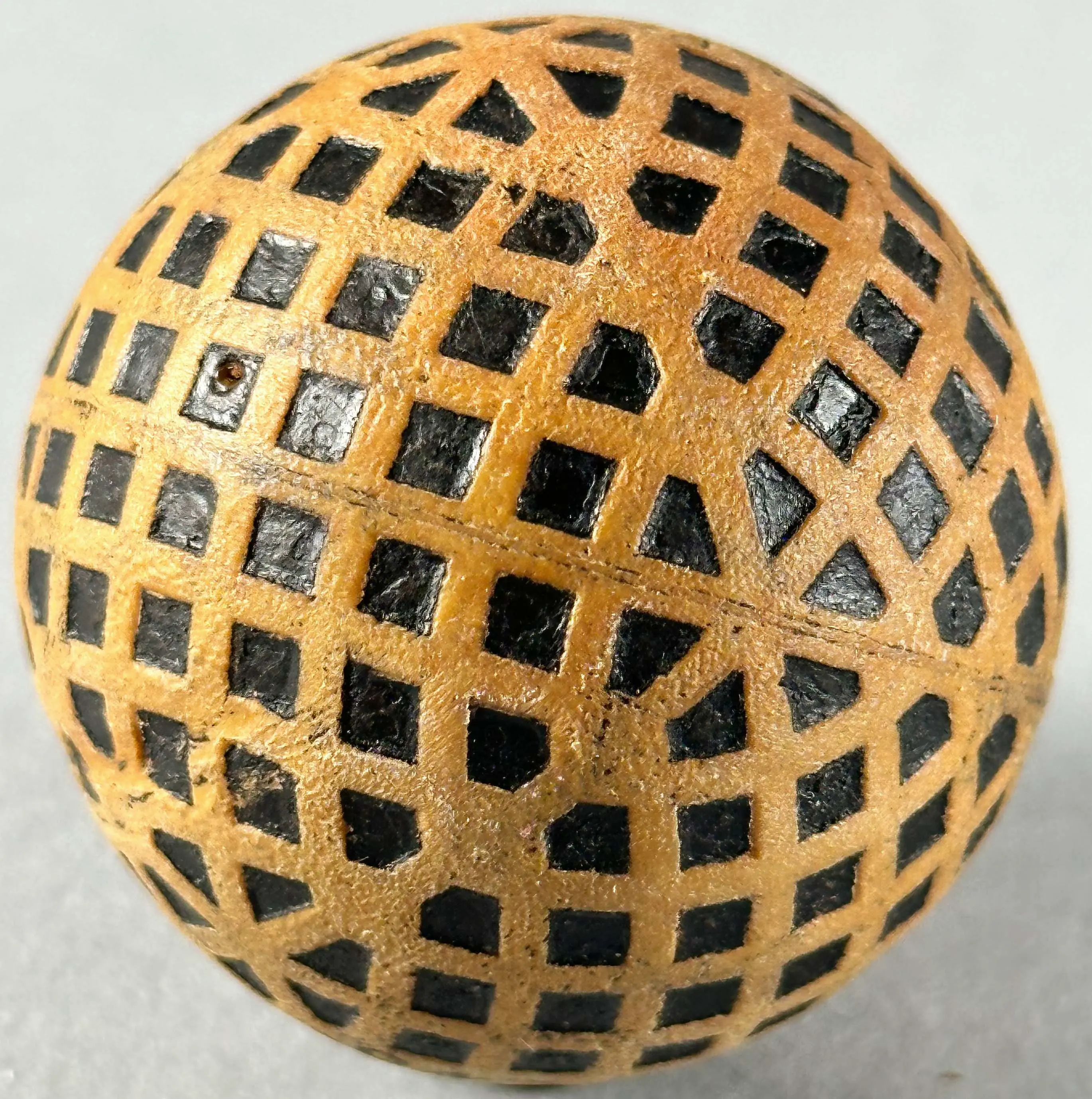

Many of the balls the fellow sent, however, made me stop and take notice. They were not early 20th century dingy white repaints, although most of the repainted balls were sold to him as from the early 20th century. Instead, these balls were painted with dramatic contrast, most often in black with the recessed portions white, but sometimes the opposite, and in other cases using unusual but repeated color schemes. Many had cover patterns that I had never seen or read about. It looked to me like many if not all these balls were recently painted by the same individual or group. There was an unmistakable consistency to them. They included a wide variety of balls painted in black, red, white, gray, and yellow in the same contrasting style.

Because there was such a significant concentration of newly painted balls with cover patterns I had never seen, I had my questions. Golf collecting is not immune to counterfeiting. Using 62 pages in the second edition of The Clubmakers Art: Antique Golf Clubs and Their History, I document over 76 fake and replica antique golf clubs, many of which have unique made-up designs.

With my curiosity piqued, I explained to the owner that there could be some problems with some of the repainted balls. He understood and was willing to allow me to do what was needed to vet the balls before putting them up for auction. None made it.

What this man called repainted balls included hand-hammered, mesh, bramble, dimple, lattice (square dimple) and unique balls with previously unknown/extremely rare patterns. For the remainder of this report, I will refer to these balls—balls painted/produced in dramatic colors and striking two-color combinations as opposed to the solid white color of a traditional golf ball—as either “black” or “decorated” balls.

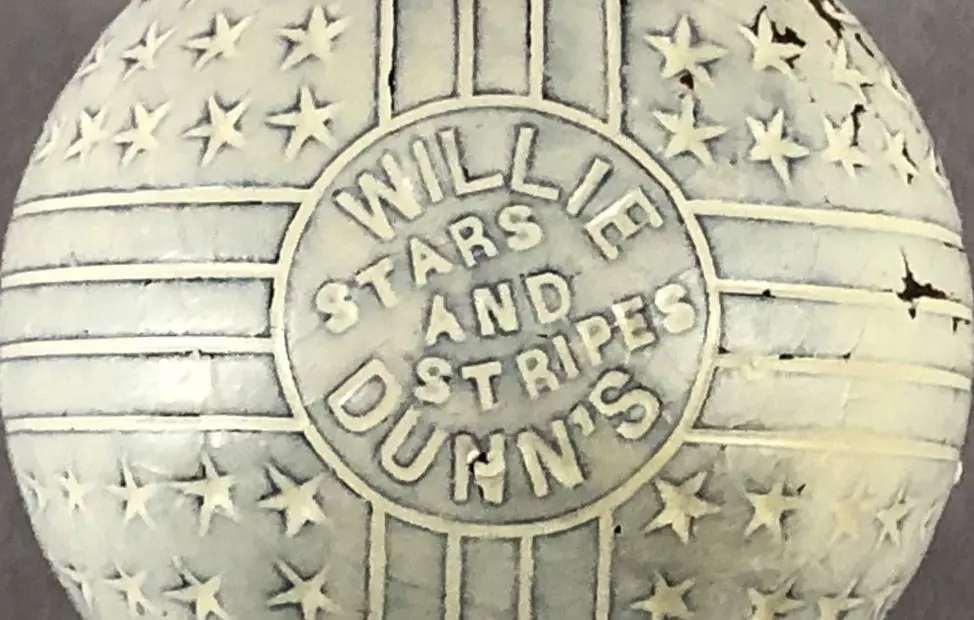

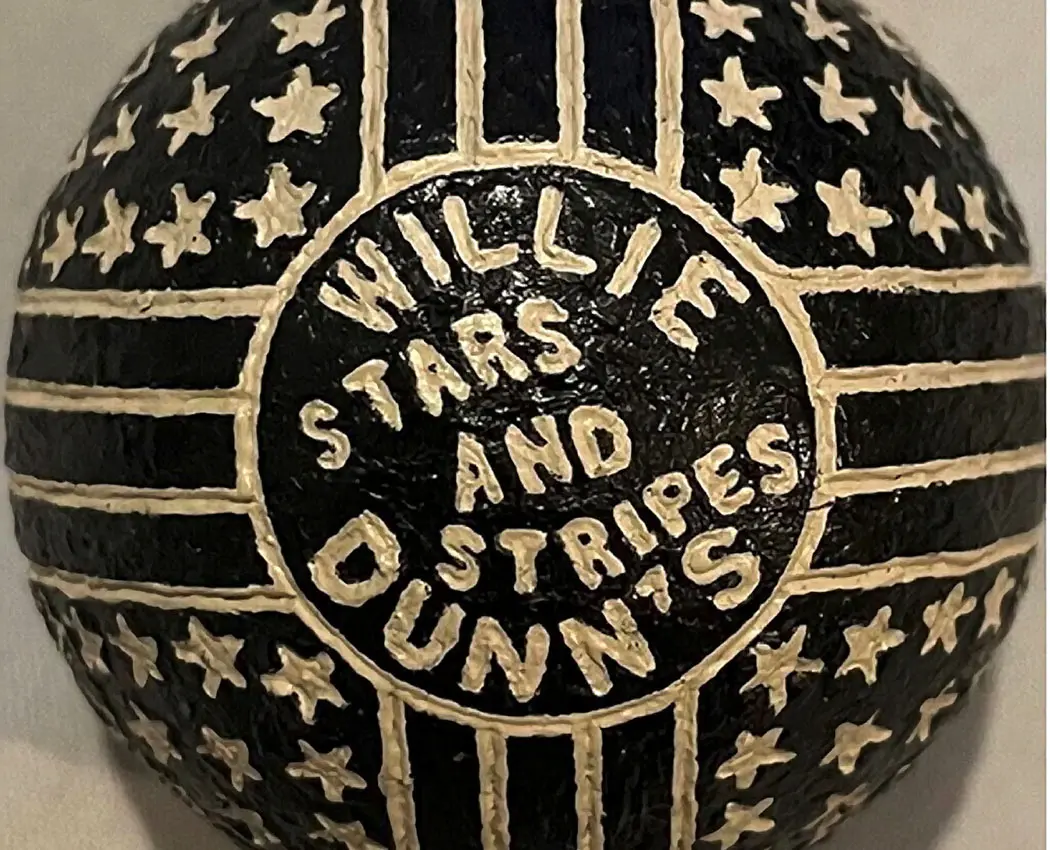

My prior experience with decorated balls was limited. Around the same time that I encountered these balls, I received a few phone calls from an individual who had been offered other decorated balls for sale. Two other individuals sent me small collections that also included a few decorated balls. Approximately five years earlier, I had seen a few black balls (including a Dunn’s Stars and Stripes) on eBay and did not quite know what to make of them. They were obviously repainted but not inexpensive. Nowhere was it stated that they were replicas or anything like that. I recall asking myself the question, “Why in the world would anyone paint a genuine 1897 Stars and Stripes ball, let alone paint it black!?”

To me, repainted balls are worth significantly less than original condition balls. After all, a new coat of paint can be put on anything, but when the original paint is gone, it’s gone—along with a key element of authenticity.

Among the decorated balls delivered to me, there was not one that I could validate as genuine. All the balls that I invasively tested and examined in depth proved to be fakes. These counterfeit antique balls appear to be created in several ways. In general, here is how I believe the ones I examined were produced:

A purchaser of some of these balls remarked that they were told the balls were pond finds and repainted because of the damage to the ball from sitting under water and mud for years upwards of a century or more... which sounded fishy to me, like nothing more than a smoke-and-mirrors story. However, the story of a continuous supply of great antique balls being gathered from lakes like eggs out of a chicken coop has apparently worked. Based on my research on the topic, I estimate that there are many thousands of black/decorated balls, and in a much bigger variety than the 100+ sent to me, currently in circulation—and they kare scattered far and wide.

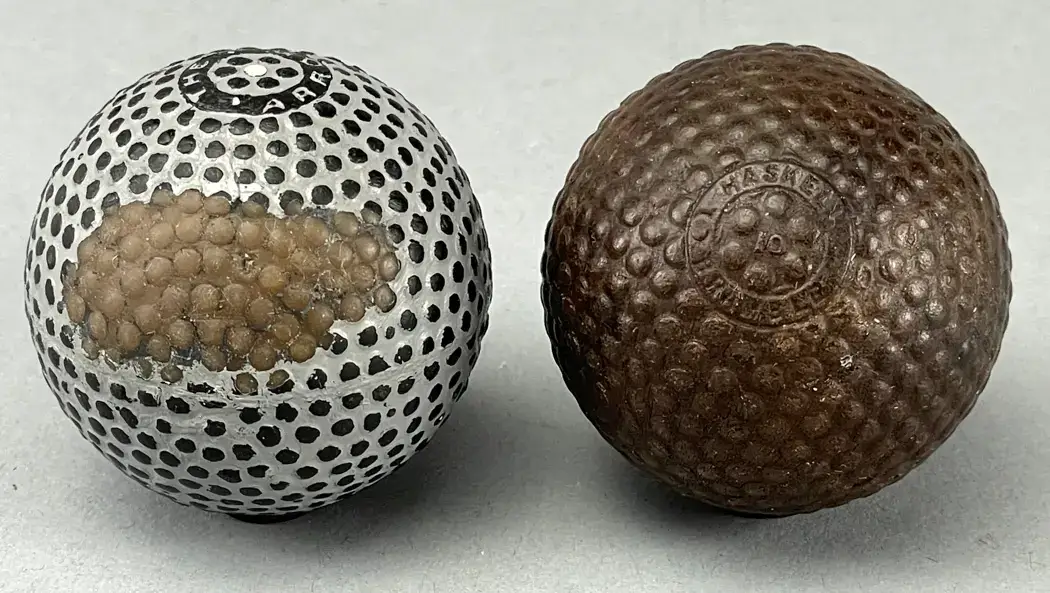

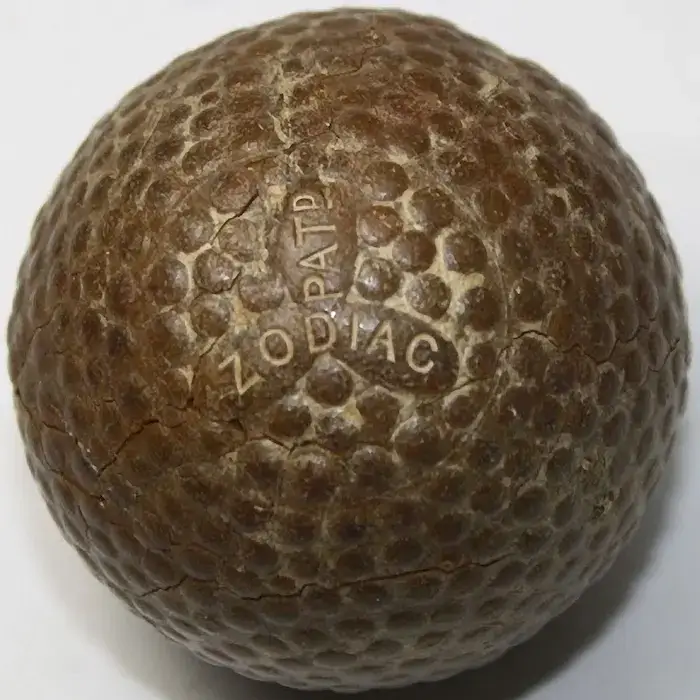

That story was flawed from the start, however, as the counterfeiters were selling purported “lake balls” that were either heavily engraved because “their surfaces had deteriorated in the water” or, in polar opposite fashion, had tack-sharp patterns and letters just like a brand new ball made yesterday. You can’t have it both ways. Circa 1890-1920 golf balls that have been underwater for a century will share an overall consistency in their condition when found, some bearing more mud staining than others, and all of them having lost a little sharpness to their lettering, patterns, brambles, etc. To their credit, some lake-found antique balls can clean up and still look quite presentable in their new light “mud-brown” color or exposed gutta percha. The appearance of the five balls shown below is consistent with reclaimed lake balls after they have been cleaned up.

A few months after I initially posted this article, the story has apparently changed. A recent buyer of two decorated balls on ebay asked the seller based in the UK where he/she obtained the balls and was told:

“I purchased those balls and most of my collection from a gentleman in the UK. He acquired a piece of property only to find out once he started to develop that it was an old golf course from the late 1800’s to early 1900’s. Once he began to develop, he uncovered vintage ball after ball. I bought most all of them.”

One of many big problems with that story is this: If solid gutta percha or gutta percha-covered golf balls were left out in the weather burrowed into and under overgrown sod that was once used as a golf course, after 100 years they would be in extremely poor condition. Their surfaces (not simply the paint) would show various stages of deterioration/rot as is consistently demonstrated by old gutta percha balls that actually have been dug out of the ground, as shown directly below.

As a result of my study, I learned a great deal and hope that it will be of help to the golf ball collecting world. Here are four points on how I currently see antique golf ball collecting in general:

Many of these decorated or black balls are crudely painted, though others are painted with great exactness. Some also attempt to duplicate the “look” of a used ball. Normally, when paint wears off the high points on an early rubber core ball, the underlying raw surface shows its usual (dark) natural color. Instead, on many of these decorated balls the dark color on the “worn” points is actually black paint intended to approximate the appearance of gutta percha while any recesses are filled with contrasting paint. In general, as you will see in this report, decorated balls are typically easy to recognize, and best to avoid.

The fallout from these imposter balls goes beyond the major losses sustained by the buyers. Because many genuine antique balls have been repainted, how can a collector determine what is real and what is not? Therein lies the rub—and the reason for presenting the results of my research here.

In order to accurately assess and evaluate purported antique golf balls, one needs to understand how genuine antique golf balls were made. Here are a few basics.

Patented in 1899, rubber core golf balls brought the production of solid gutta percha golf balls, first tried in 1845, to a conclusion by roughly 1903. The continued use of gutta percha to make covers for the new wound rubber core balls, however, was fundamental to the ball. The covers on the early rubber core balls were made from either pure or supplemented gutta percha. In 1902, there were no less than 17 British patents that called for making the cover or surface of a golf ball from gutta percha or gutta percha mixed with various additives. During the ensuing years, ballmakers often mixed various additives such as india rubber, vulcanite, balata, chemicals, minerals, and other materials with gutta percha, the ballmaker hoping to either make a cheaper ball or devise a cover that would be more durable and/or improve feel, distance, accuracy, etc. In the vast majority of instances, however, the gutta percha used to make golf ball covers was dark brown, the same basic color as the gutta percha used to make solid gutty balls during the 19th century.

From 1899 to the early 1920s, gutta percha covers remained in widespread use. An article titled “The Making of a Golf Ball” in the October 1904 issue of The World’s Work reports:

“Dissect a rubber cored ball and …. you may dig out with your scalpel an inner core of wood, cork, vulcanite, or leather; you may find it wound in rubber threads or rubber tape, and a glance at the cover will reveal the purest gutta percha.”

The Travelers Standard, July 1913, (p. 213) described how golf balls were made as follows:

“A core of hard rubber, cork, or wood [was] wound with rubber tape under tension, and an outer covering of gutta percha was then molded around this winding. Two sizes of windings were used—a primary one of rubber thread, and an outer one of rubber tape.”

The September 1918 issue of The American Golfer published a letter that asked what is “the outer layer on the golf ball, is it rubber the same as on the inside of the ball?” The editor, Walter Travis, responded, “The cover or shell of the rubber core ball is largely composed of refined gutta-percha, with an admixture of balata.”

In his article On the Inside of a Golf Ball published in the September 6, 1920, issue of The American Golfer, Walter Trumbell described the construction of a golf ball in part as follows:

“This core is placed in a machine and many yards of rubber band or tape is wound upon it…. When the tape is all put on, the ball looks nothing so much as a mass of extremely emaciated angleworms. On top of this a shell of gutta percha is moulded, varying in thickness from 1/16 to 1/8 of an inch. Then the ball is painted. Four coats of paint are general.”

In the December 17, 1921, issue of The American Golfer, O.B. Keeler described the golf ball as a “lively and expensive globule of rubber core and rubber strands and gutta-percha shell.”

Before Surlyn, a synthetic resin, was used to make golf ball covers in the 1960s, covers were made out of gutta percha or balata either entirely or in large part. They could be mixed together, combined with various chemicals and other ingredients, plus they could be processed in a variety of ways including extracting and combining resins and vulcanizing. Even so, gutta percha and balata were the two main materials used to make covers prior to Surlyn. Natural rubber (para rubber or india rubber as it was often called) was used to create the rubber thread/strips that wound around the cores of early rubber core balls. Para rubber covers were tried on a few balls, but with poor results.

There are two reasons why it is important for collectors to understand that gutta percha was the primary material used to make golf ball covers during the initial decades of the 20th century. First, such covers will typically have a dark brown color depending on what if anything was mixed in with the gutta percha. Second, gutta percha covers typically make a distinctly bright clicking sound when they are lightly bounced on a hard surface (just release the ball from ¼” above a rock-solid countertop and listen). The sound is much like the click made when two pool balls collide.

In some instances, an early 1900s rubber core ball with a gutta percha cover will sound so much like a solid gutta percha ball that it can be nearly impossible from sound alone to tell the two apart. Typically, if the cover is a gutta percha composition, it will still make a clicking sound but not quite as sharp—there are degrees here, especially if much para rubber was mixed in, or so I believe. Balata covers which came into prominence later during the 1920s and ‘30s can also make distinct but differing clicks depending on the process used to form the cover and the purity of the balata—whether it has additional material or additives mixed in. In some instances, balata-covered balls sound like they are made from solid gutta percha, in other instances they can sound muted.

Of course, there are other factors beyond the cover material that determines the sound an antique golf ball makes when bounced. For example, the tension of the winding, if the winding has hardened or solidified over time, the amount of pressure used to compress the core (some were slightly oversized) when the cover was applied, and the connection of the cover to the wound core are all elements that can influence the sound. The center of the core, which was made from a wide variety of materials such as para rubber, gutta percha, liquids, celluloid, chemicals, air, metal, etc., can also influence sound if only to a slight degree. The cover, however, normally plays a sizeable role. While there can be variations in the sounds made by rubber core balls, the critical point is that solid gutta percha balls and rubber core balls with gutta percha covers will typically sound much different from old balls remade with new rubber covers as with many of the counterfeit balls described hereafter.

It should be noted that, in addition to the typical dark brown gutta percha, both black gutta percha and white gutta percha was advertised as cover materials by a few ballmakers. An exposed black gutta percha cover simply looks more black than brown. It has been my experience that an exposed white gutta percha cover will appear reddish brown to yellow depending on what it is mixed with, and it will have a genuine degree of translucence. The lighter the yellow color, the more translucent its surface (especially any raised edges such as in its name/pattern) will look when viewed with a jeweler’s loupe in bright light.

Soft para rubber (natural rubber) was the standard material used to make the inner elastic thread and tape wound around the spherical center in a rubber core ball. Para rubber covers were tried on only four different balls that I know of but with poor results. Such covers look similar to dark brown gutta percha in color. Balata covers were tried on a scant few balls prior to 1920 for a few reasons. It was much harder to source, more expensive than gutta percha, and not as durable. Eventually the supply of balata increased, and ball manufacturers figured out how to make balata covers that were better than gutta percha covers. Consequently, during the 1920s and ‘30s balata was used more and more, sharing the stage with gutta percha before becoming the main ingredient used to make covers in the ball-making industry for many years.

Golf balls were made from molds for decades before the rubber core golf ball was patented in 1899. Over time, the molds became more refined. By the 1890s there were businesses in the UK that supplied molds to the golf ball industry. These molds were made by professional craftsmen and to perfection. The December 1, 1899, issue of Golf Illustrated promoted one company in particular:

“The essential requirements for the remaking of balls are a first-class engraved mould and a screw press, and we cannot do better than recommend our readers to the appliances made by John White and Company, engineers, Edinburgh, who can supply the moulds engraved to any pattern desired, and whose goods are of first-class manufacture.”

White advertised “golf ball moulds in ‘Haskell,’ ‘Lynx,’ ‘Bramble,’ ‘Silvertown,’ ‘Ocobo,’ &c. markings” for many years in the major golf magazines from the early 1890s into the 1910s.

In the earliest patterned molds, the pattern was engraved into each half of the mold. A professional engraver would literally cut in the pattern to be reproduced, which typically consisted of lines. According to “Morris,” as published in the April 9, 1880, issue of The Illustrated Carpenter and Builder, “Golf Ball moulds are made from gun metal in two halves, both halves grooved out instead of hammering.”

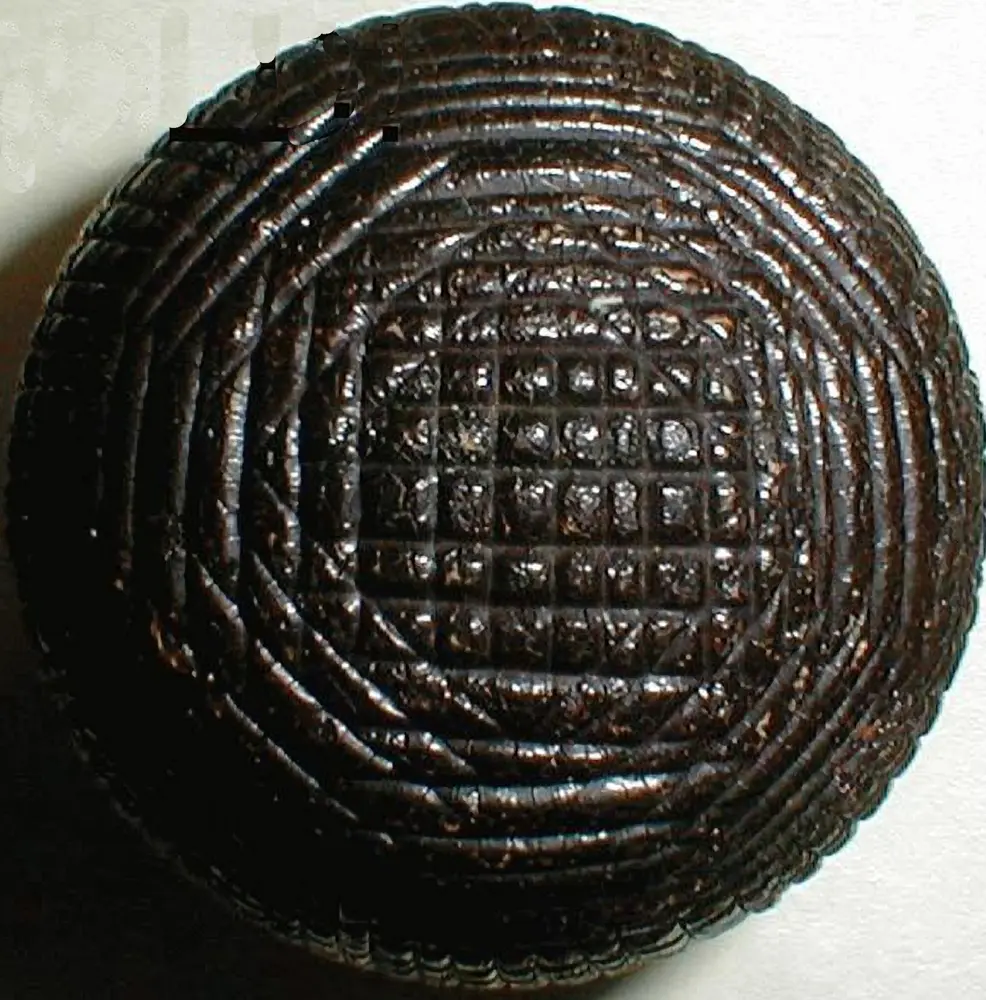

By the mid 1890s master balls were also being used to make patterned molds. A master ball had the advantage of being able to make multiple duplicate molds, which was most helpful if the pattern was intricate or production sizeable.

Those who desired a mold could purchase a well-known pattern that was in stock, or they could have one or more molds made with their own, unique pattern. Making a mold with a new pattern, however, could be quite expensive. To make a mold from a master ball, the first step was to craft the master ball. Whatever the new pattern was to be, it needed to be perfectly formed on the surface of a brass master ball. Again, once a master was made, it could be used to cast multiple identical molds.

The craftsman who made master balls and engraved molds were truly artisans. The exacting details found on various patterned golf balls such as Henry’s Rifled with its graduated spiral pattern, Helsby’s Link with its raised chains, Stow Woodward’s Burbank swirling whirlwind ball, and Cochrane’s map of the world ball with its continents, countries, oceans, and brambles are testimonies to their incredible skill. It’s clear that the master balls and engraved molds that produced antique golf balls were meticulously crafted to an exacting standard. With all that was at stake—the large amount of money spent to make the molds and the need to sway golfers to buy the finished ball—the pattern needed to be as close to flawless as possible. Many of the engraved decorated balls that will follow stand in stark contrast to the beautiful and exacting workmanship of the early 20th-century ballmakers.

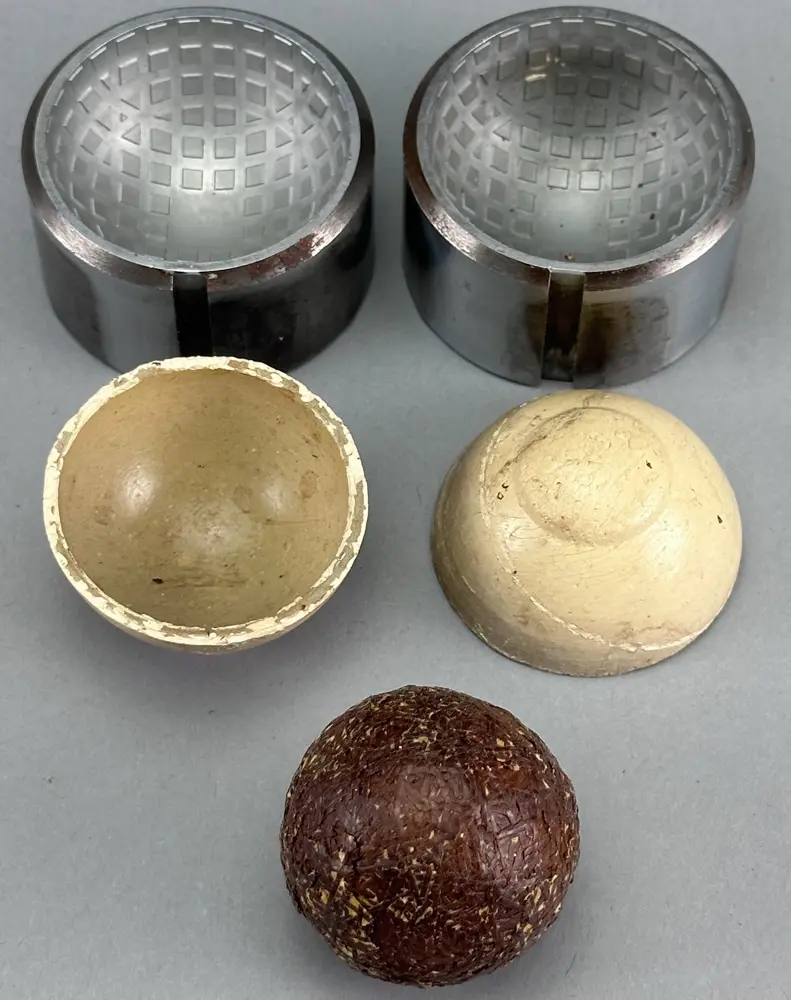

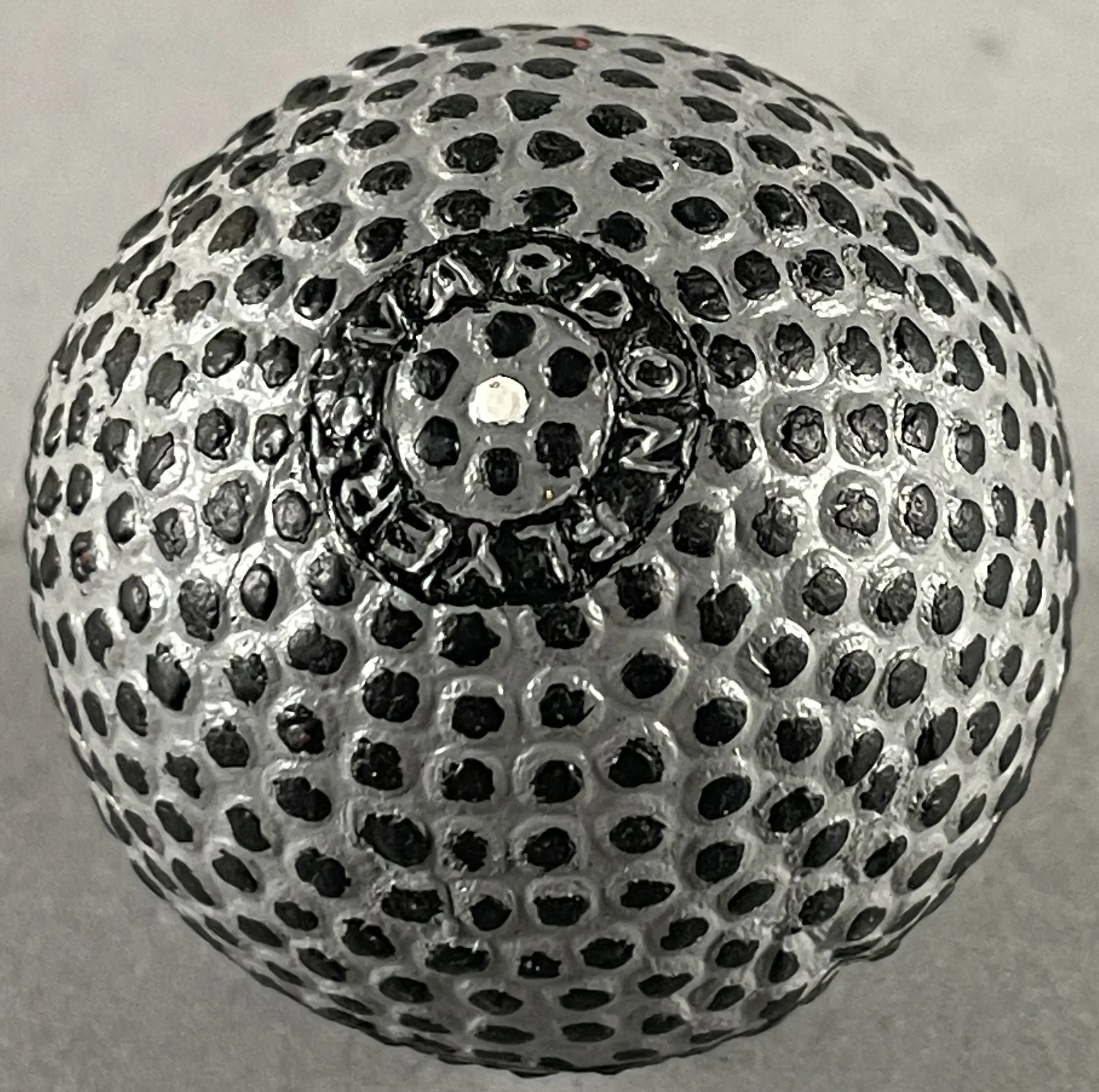

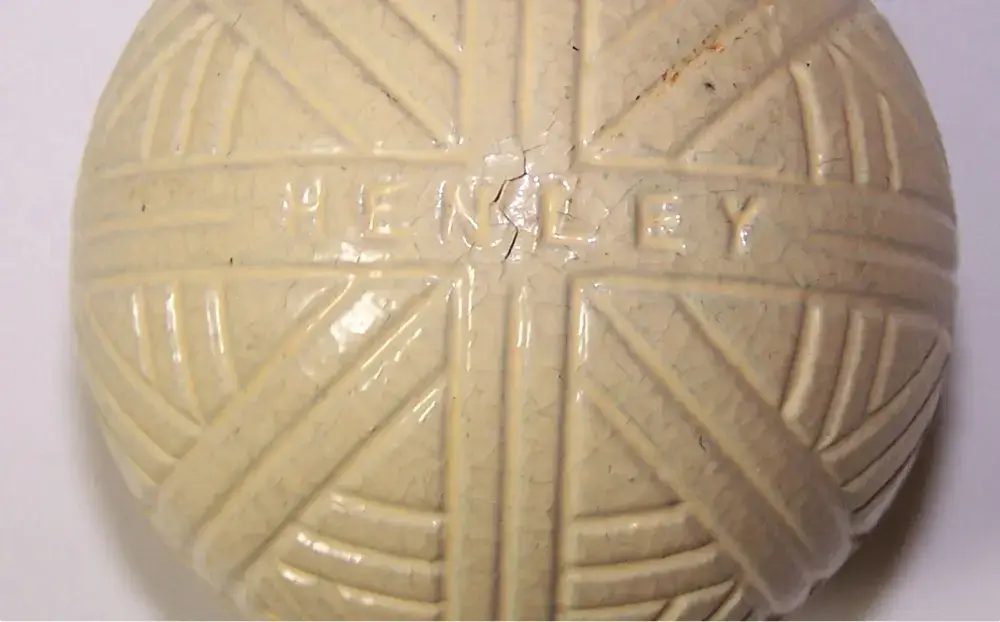

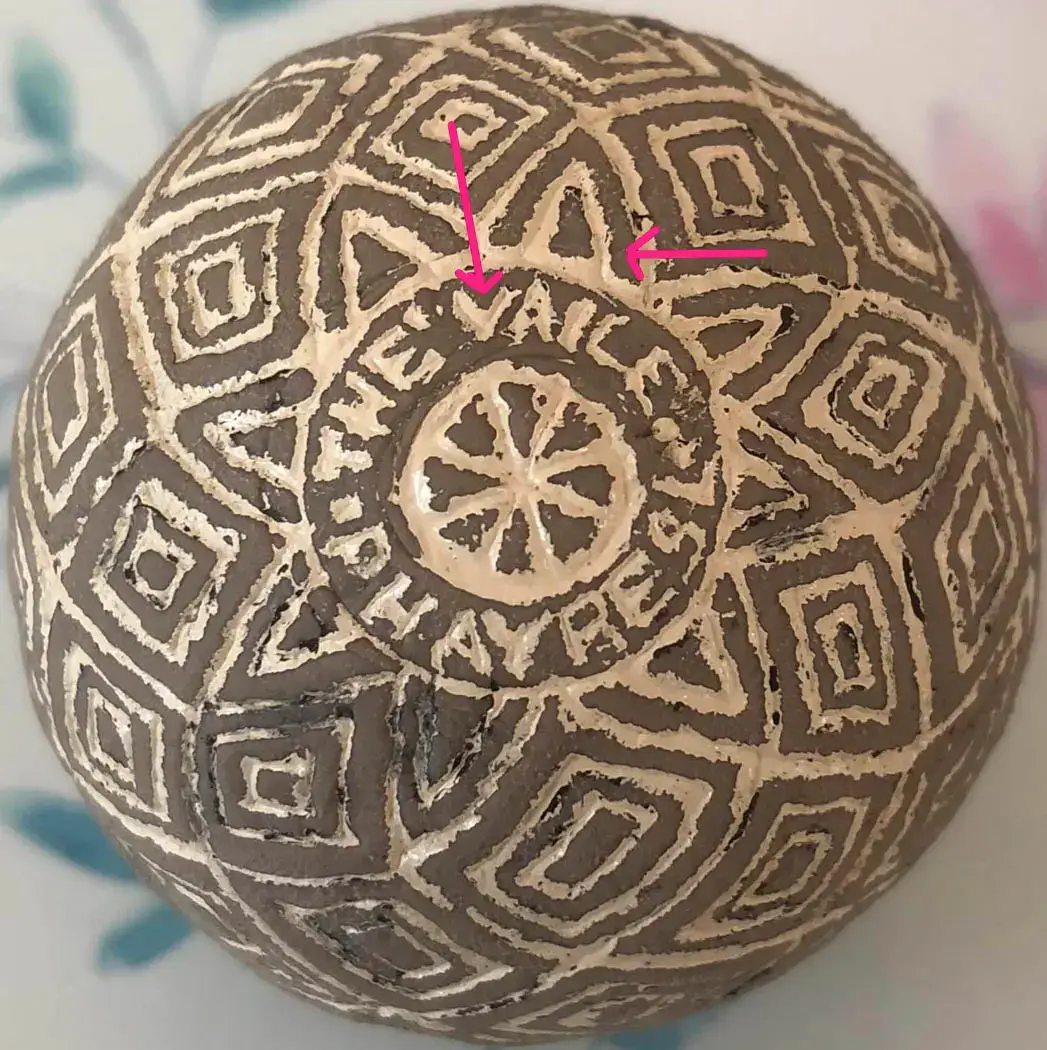

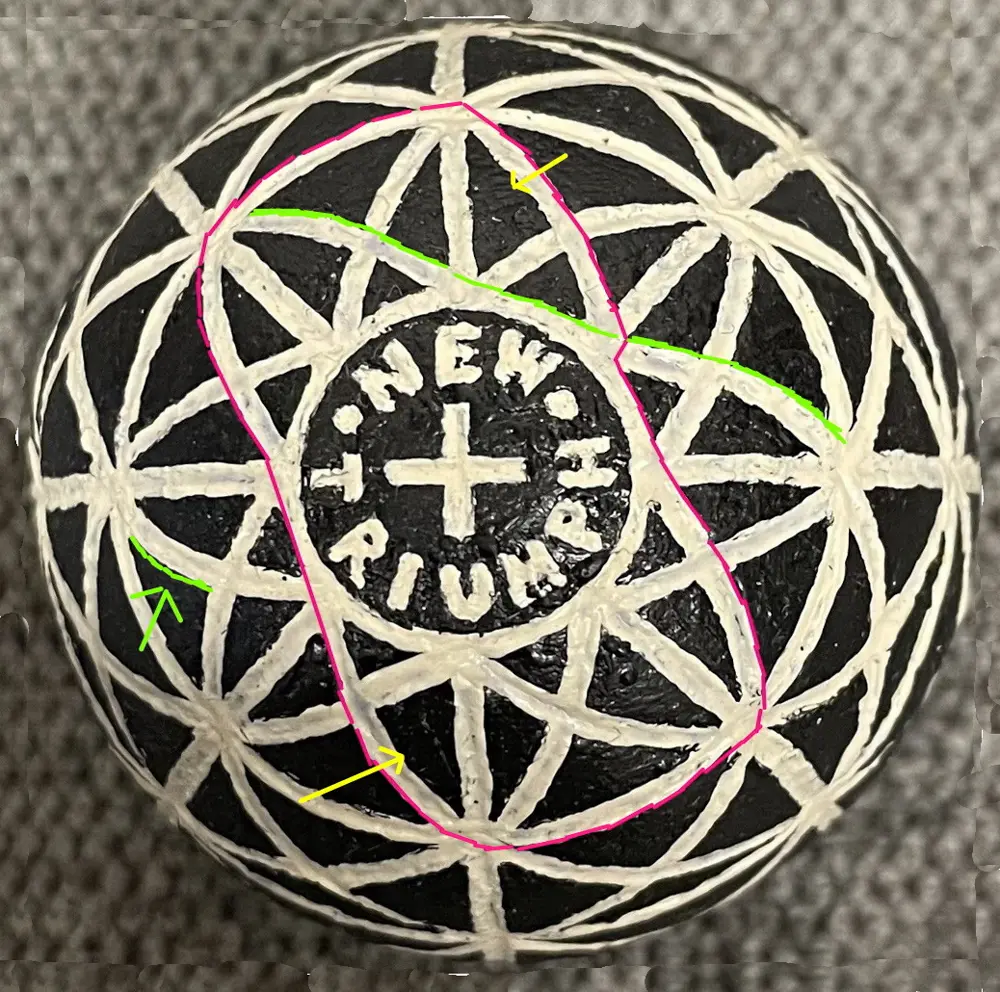

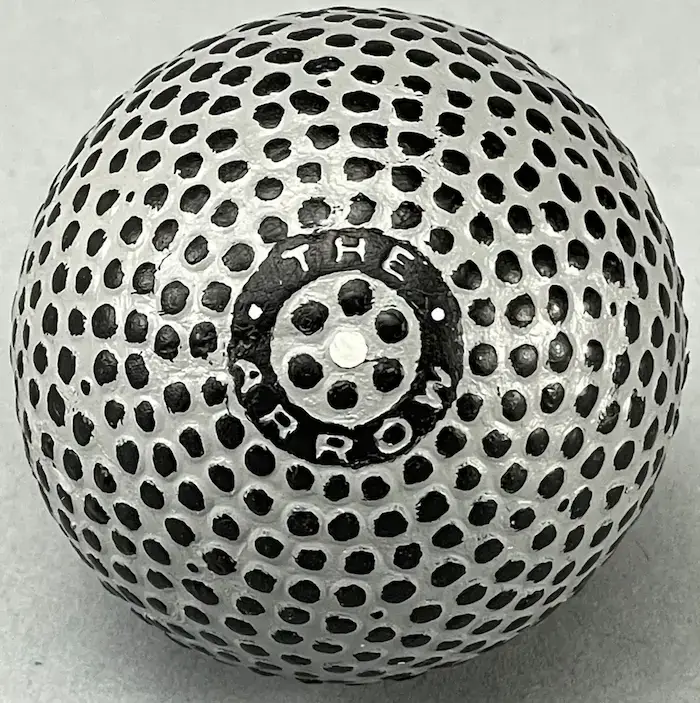

Speaking of flawless, see Image 1 here.

This intricate incised brass master “half ball” (shown both assembled and taken apart) was offered in Sotheby’s July 11, 1994, sale with the description in part as follows:

“The difficulty was removing the patterned master ball from the mould. John White, North St. Andrews Street, Edinburgh, overcame this problem by making these half balls. One ‘half’ comprised seven pieces, each piece was hand filed and machined to an accuracy of 1/1000 of an inch, then sent to have the design of the golf ball maker engraved onto it. This particular ball was made over 90 years ago. It cost as much as £30 to have one ‘master ball’ engraved. On completion of the half ball it was accurately placed in the centre of a brass cup, and white molten metal was poured in around it. Removing the half ball, with its engraved indentations, from the solidified metal was the main problem, hence the reason that the half ball was made in seven pieces. By taking out each piece in sequence the master ball came clear out of the mould. Two moulds would be made from the ‘master ball’ so that the cover could be placed—in two pieces—one in each mould. The elastic cored ball would then be placed between the two moulds and the cover pressed on.”

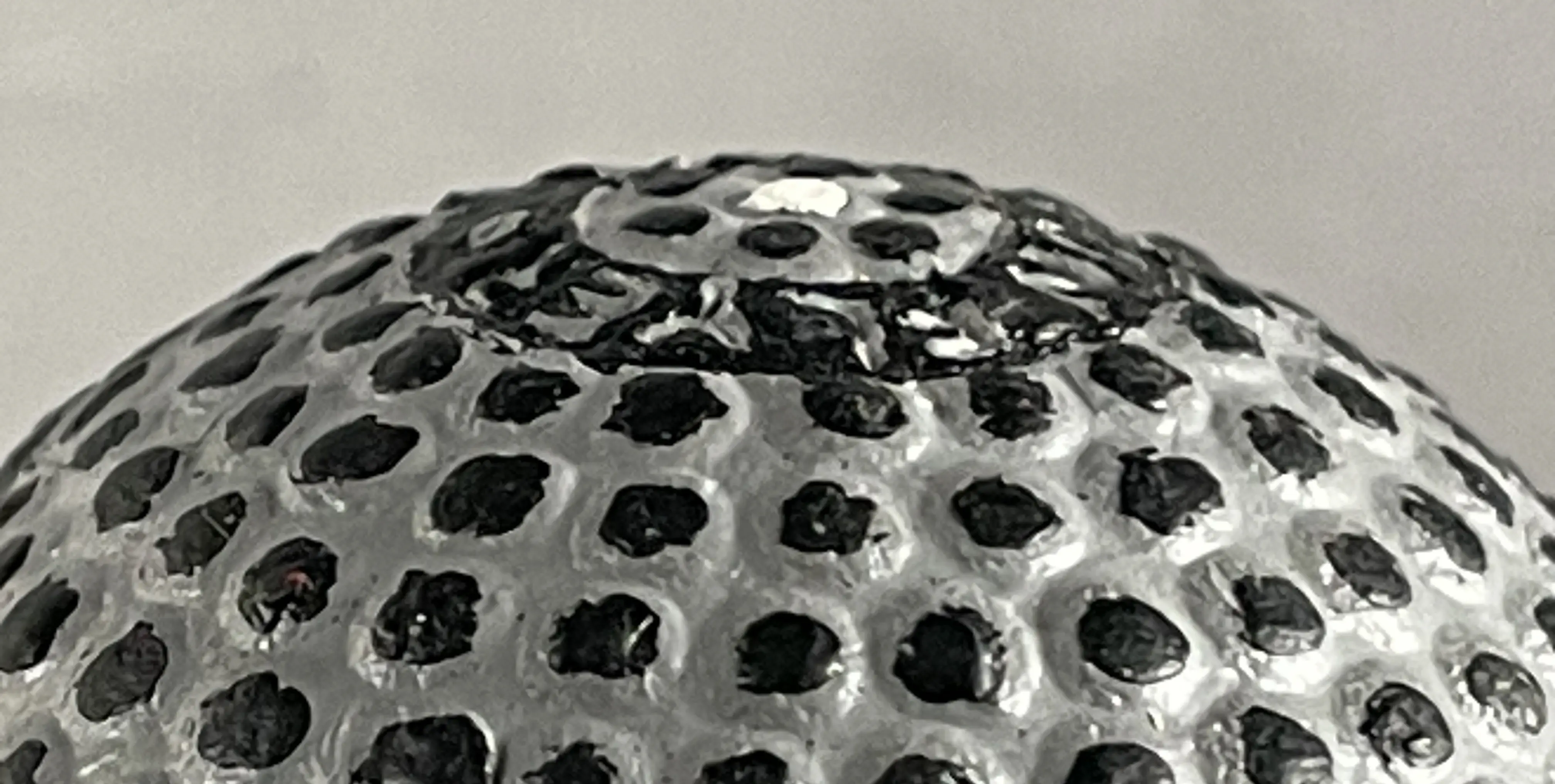

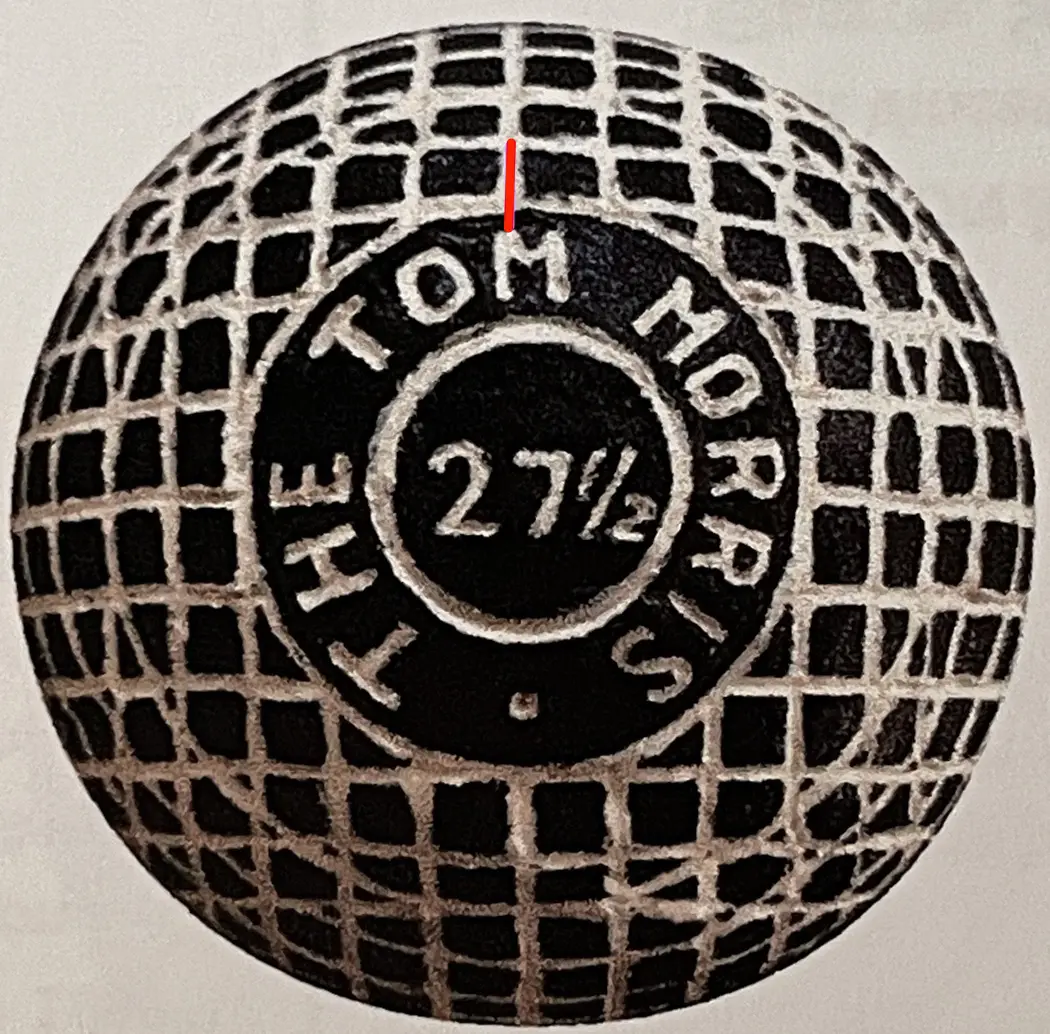

As can be seen in Image 1 above, the production of a master ball was accomplished with exacting precision. Such was also the case with the more common solid brass master balls, such as the extremely heavy Thornton's Patent 27 ½ brass master ball shown in Image 2

Once a master ball was crafted, the next step was to make the mold. The bramble ball mold in Image 3 here consists of ten pieces. It could make balls marked with two different names and two slightly different patterns (or possibly ball sizes). The outside of the two large pieces is marked with a British patent number. J. Murry and A. Levack filed their application for this mold in June of 1895.

Four interchangeable small pieces, four interchangeable medium size pieces and two large pieces make up this ten-piece mold. The small pieces are name plugs that fit into the middle pieces. Two of the middle pieces fit in the two larger pieces. There are two screws in the sides of both large pieces; loosen the screws and the inner molds will come loose. There is a hole in the bottom of each large piece to aid in the removal of the inner piece. There is also a centered hole in the underside of the middle pieces, to aid in the removal of the small name pieces. The four small pieces are actually two matching pairs. A different ball name is on each pair.

As can be seen in the images above, master balls and the molds made from them, be they ten pieces or two pieces (as most were), were the product of professionals—sculptors, engravers, and foundries. A single master ball could produce many identical molds.

By the 1920s, golf balls were made in die sunk steel molds. As reported in 1923:

“Golf ball centers are usually covered with gutta percha or balata in special steel molds. Their manufacture necessitates special tools and specialized training and skill on the part of the workman who finish the cavities by hand methods. Each mold cavity is die sunk or cut from a solid block of special quality steel. The raised spots on the mold cavity that produce the dimpled markings on the surface of the ball are most accurately located and cut in relief by special die sinking tools. The bottom of the cavity is bored to receive a plug with surface concaved to the same radius as the ball cavity, and bearing in raised characters the name of the ball. This feature requires exceptionally careful work. When completely cut, and engraved, the cavity is hand scraped and polished free of tool marks and undergoes heat treatment to prevent rusting. Such a steel mold is permanent and accurate and a marvel of the art of die sinking.

“The process of making it is slow and expensive. The high cost naturally restricts ball manufacturers’ investment in such equipment, and discourages changes in design of markings and production of special types.

“Balls molded in a die sunk steel mold of the sort described are remarkable for perfection. However, the growing popularity of golf is increasing the demand for balls and emphasizing the need of enlarged mold equipment. The solution of the problem of excessive cost without loss of the accuracy and perfection of the steel golf ball was found in the process and application of die casting.

“Die casting is the process of making castings from non-ferrous alloys by injecting the very hot fluid metal under high pressure into heavy steel dies provided with an internal water circulating system for rapidly cooling the casting…

“The die used for casting golf balls is of the same type as that for die casting in general. It is separable, built of steel, and contains a copper pipe system for internal circulation of water for cooling the casting. It has also an air outlet. In the case of golf balls several cores are mounted in the die and the cavities assembled in gates to make several molds at one casting.” (India Rubber World, Nov. 1, p.83)

Duplicate molds were required in order to provide the large number of molds needed to produce the massive number of golf balls sold each year by 1920.

Once die cast golf ball molds were introduced in the early 1920s, up to twenty-five or more molds could be made by an automated machine during one casting. As a result, the cost to produce golf balls dropped, production speed increased, and balls became much easier to make—with no loss in accuracy, markings, size, or perfection when compared to balls produced from die sunk molds.

After a ball was made, it could be remade once it started to show notable damage or wear. Remade balls were a staple of the golf ball market during the early 1900s. They were typically sold with “remade” marked on their cover or else the ball’s name was advertised as a remade ball.

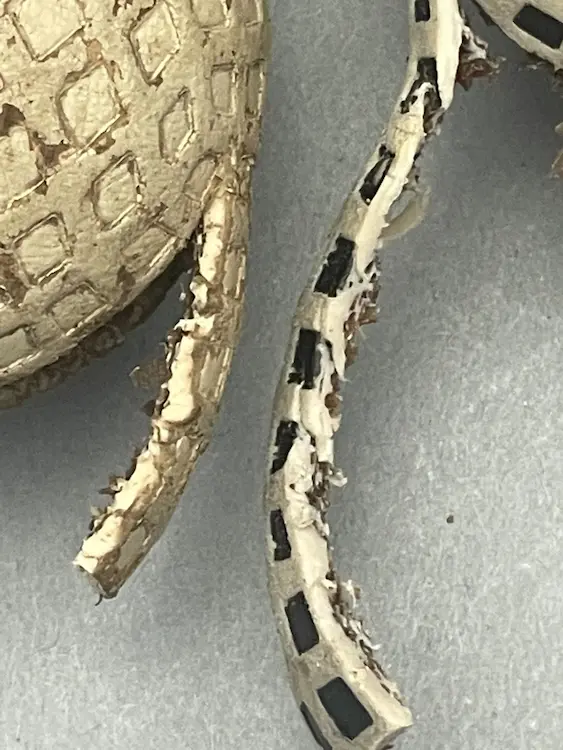

The image above left shows a wound rubber core with its original lattice pattern cover removed.

The image above right shows both halves of a c. 1930 lattice pattern ball mold, two c. 1930s balata shells used to form a cover, and the neatly wound rubber core removed from the ball above left. Back in the day, to mold or remold a golf ball required either a new or used wound rubber core. Next, it was placed between two thin shells (previously molded from either gutta percha or balata) and everything was heated/molded together inside a ball mold. The exterior of the new cover would bear whatever pattern was on the inside of the mold. After the ball cooled, any excess material forced out where the two mold halves met when pushed together under heat and pressure was trimmed off, and the ball was ready for painting.

If somebody wanted to make or remold a rubber core golf ball today, a metal mold is no longer necessary. Soft molds can be formed around a genuine ball and, after curing, replicate the genuine ball. However, it would not be an exact replica for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is that the copied castings produced so far are not made from genuine gutta percha or balata.

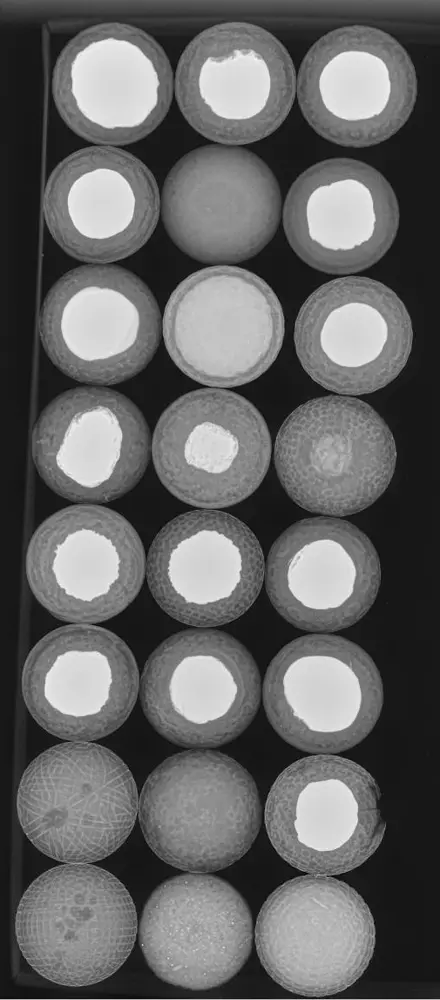

Above, 25 rubber core golf balls from the early 1900s demonstrate three fundamental points about golf ball covers made prior to the early 1920s:

Unlike rubber, white gutta percha covers are plastic-like with a genuine degree of translucence especially when viewed under magnification. The covers on the few Goodrich balls advertised as made from “pure white gutta percha” that I have seen are a translucent yellow, like it is on the Goodrich Whippet shown above. The reddish-brown white gutta percha cover on the Spalding White was advertised as made from a “purified” white gutta percha produced under a patented process.

Note: In the image above, there is one white gutta percha cover for every four dark brown gutta percha covers. In reality, white gutta percha covers are far more rare. Also note that during the 1920s and ‘30s, ballmakers would sometimes use yellow varnish and/or a thin layer of material, sometimes yellow, under the finish coats of white paint. In the early 1930s, Silvertown, to name just one ball manufacturer, used a thin film of vulcanized rubber over top of the winding to prevent their gutta percha covers from penetrating the elastic thread.

Consequently, chipped paint on a balata cover can reveal what appears to be white gutta percha, but it’s not. It’s an undercoat of yellow

varnish or thin layer of material used to improve the qualities of the paint and the ball itself. As found today, many 1920s and 1930s balls

have a coating, primer, and/two or more layers under their white exterior. In many instances, the color directly under the white paint as seen

where it is chipped or worn is not the color of the cover's base layer. I have personally witnessed this in a number of worn 1920s and ‘30s

balls as well as some of the balls that I have stripped and cut apart (see 4.22 Dunlop Lattice Ball).

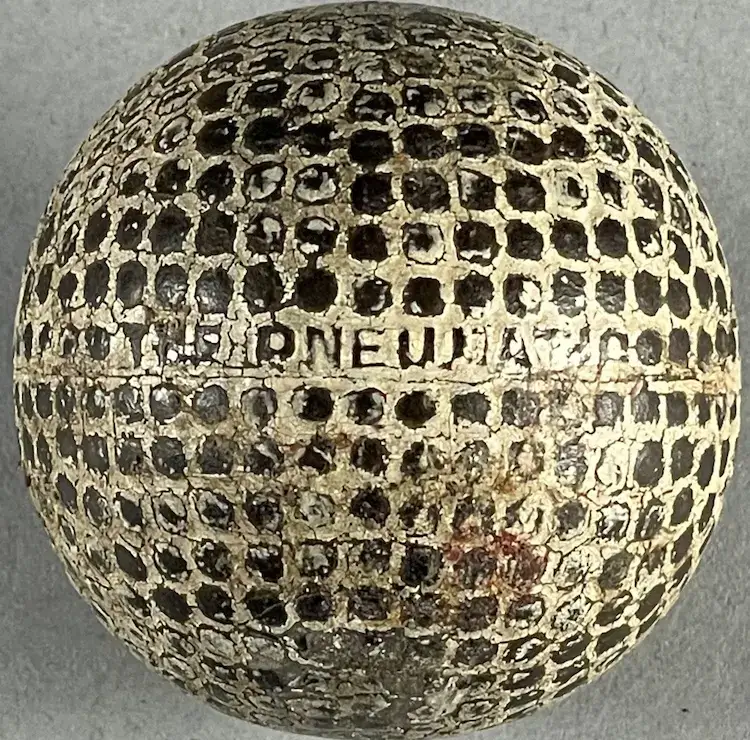

For sake of reference, the 1906 Goodyear Pneumatic golf ball shown here is one of only four early 20th-century golf balls I have

found that were advertised as having a para rubber cover. I have never seen any of the other three. As shown on this ball, the color of its para

rubber cover is consistent with the black/brown color of the para rubber cores shown in the first image of this section.

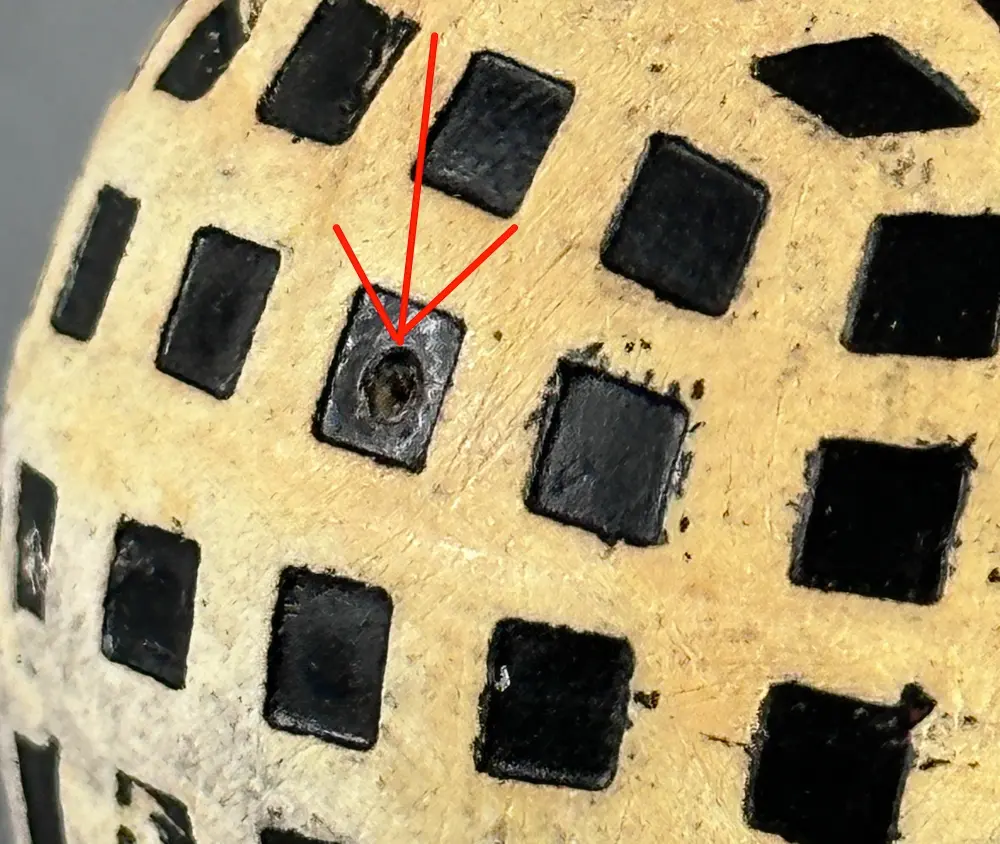

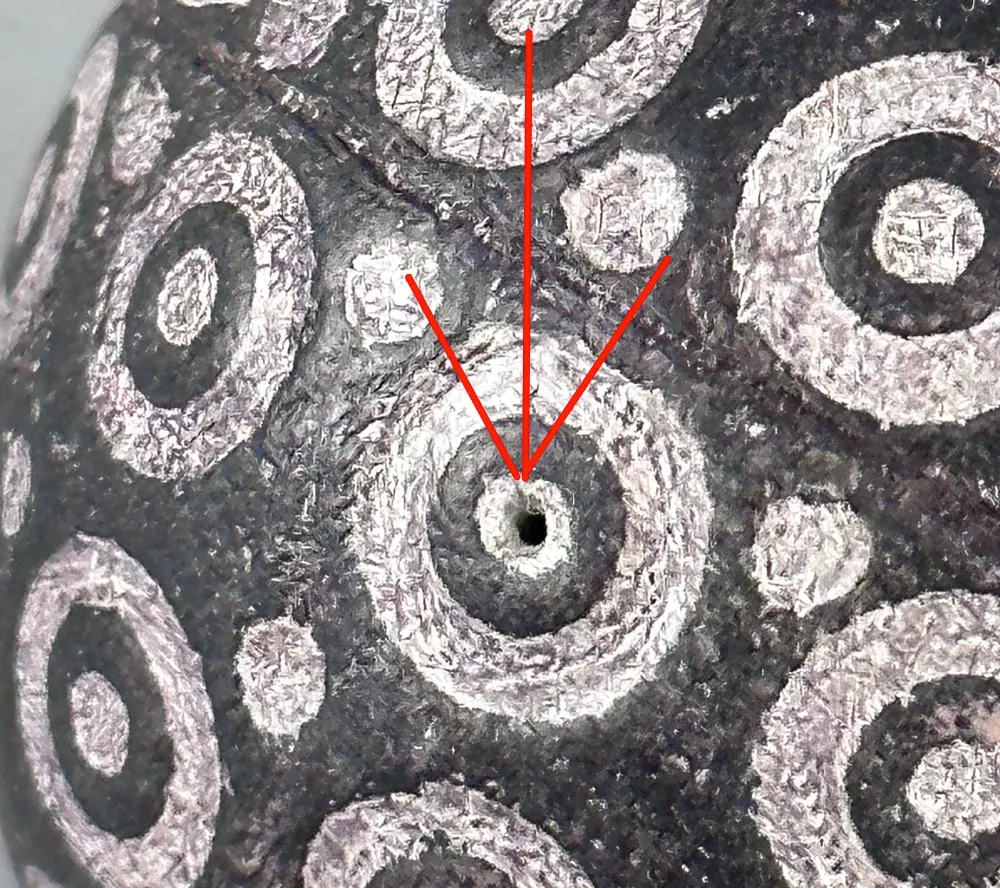

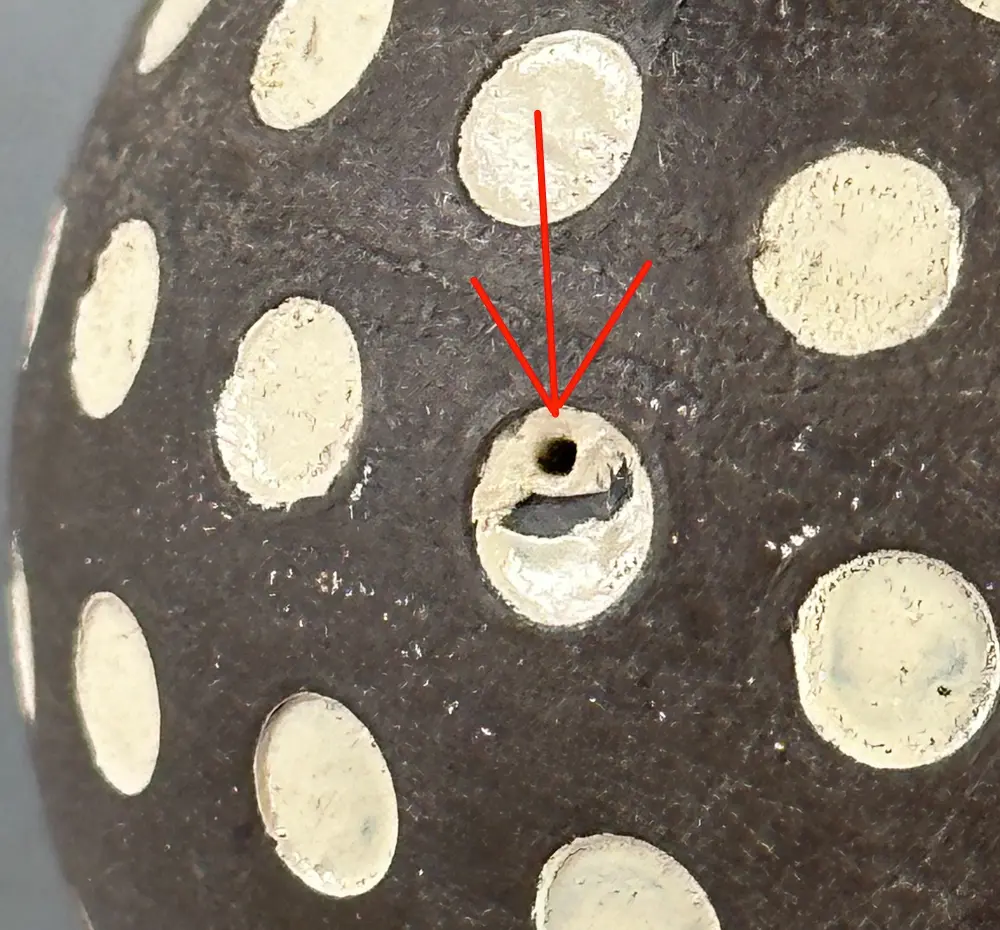

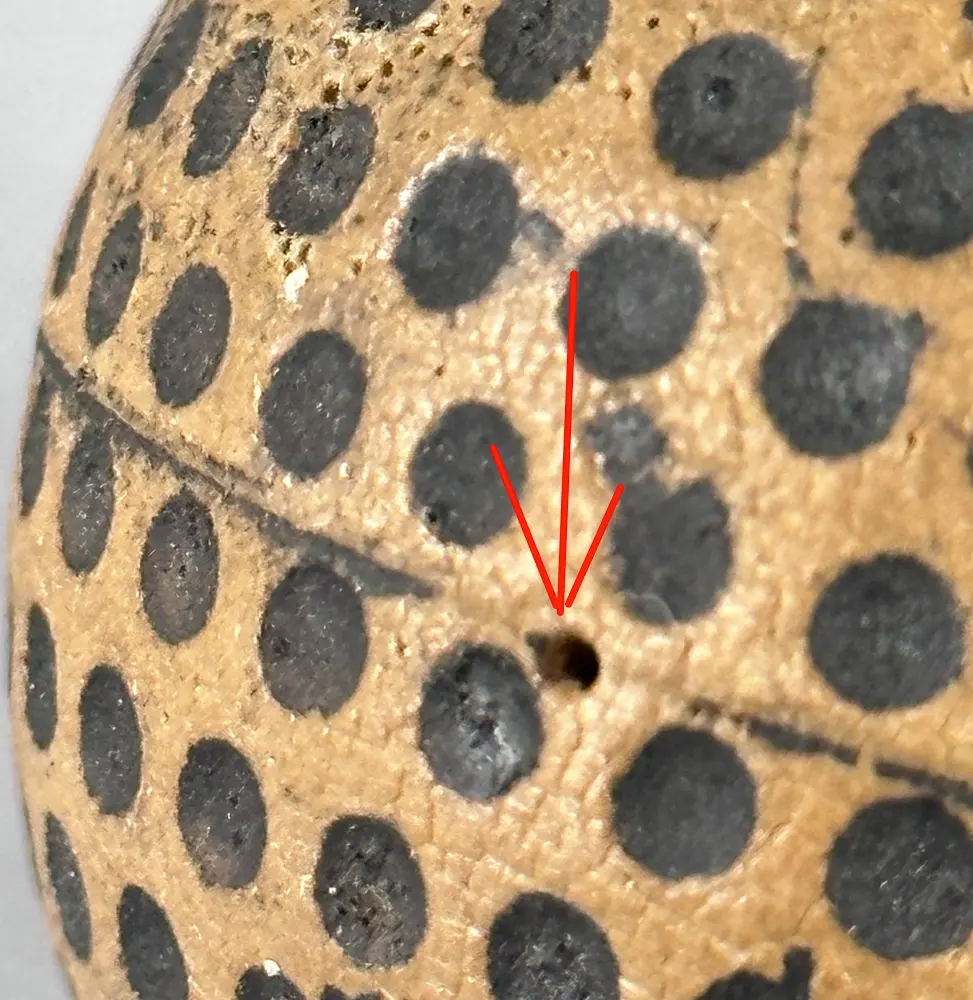

The above statement might seem obvious if you are a golfer or golf ball collector, because no genuine golf balls from any era were ever made with holes molded into their covers. It would be counterproductive to the efficiency and durability of the balls. Besides, what golfer would ever buy a new ball that was made with a literal hole, an obvious blemish to begin with, in its cover!

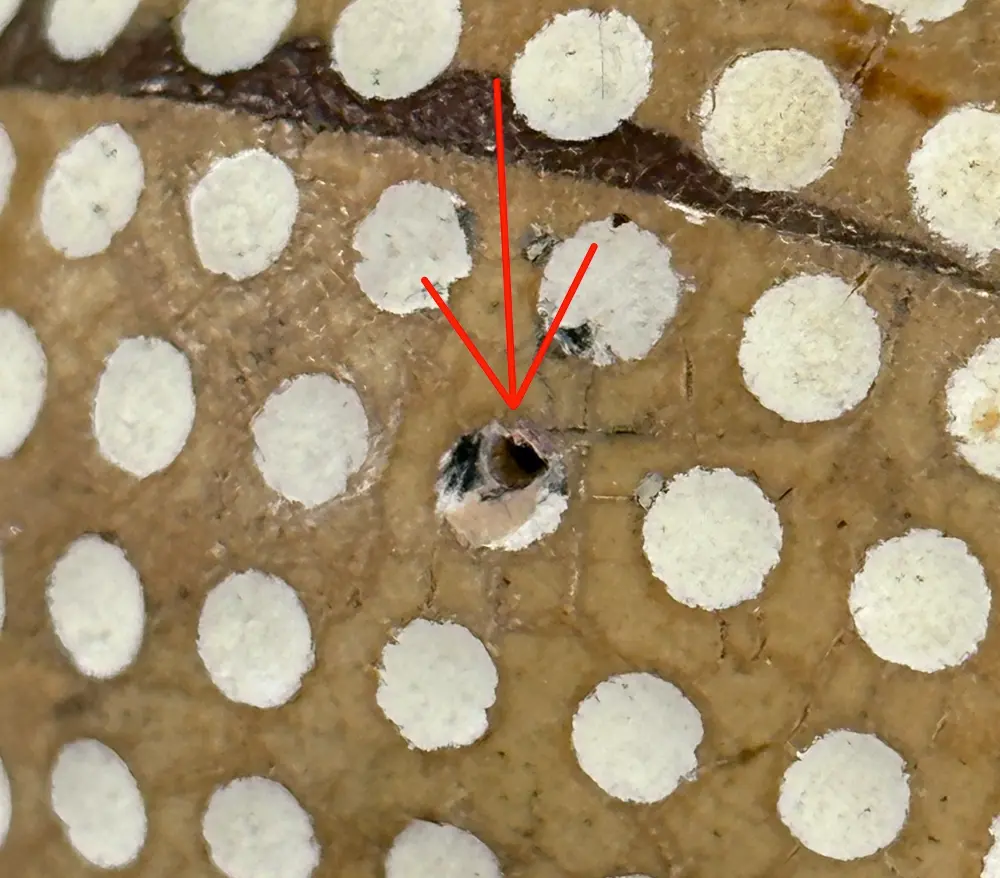

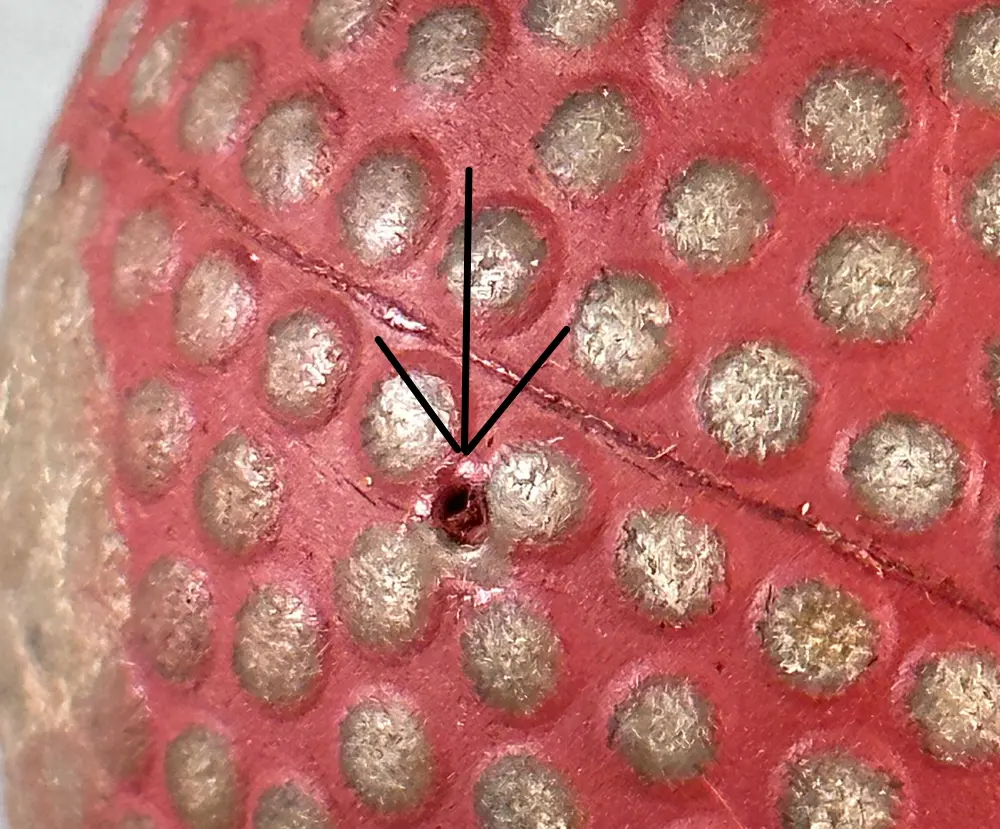

I included the statement above because several decorated balls I examined were, in fact, made with a small hole molded into their covers—as shown in the collage image of 17 decorated balls (including the star Challenger ball) below. According to the people in the molding business that saw some of these balls, the hole was made to support the core during the process of molding a new rubber cover onto an old core, so the core would not settle to the bottom of the mold before the casting cured. For more about this anomaly, see Section 5.1.

The top three balls on the right display the names Ace, The Royal, and The Jockey. Below them in the next row is The Capo, The Challenger (center red bramble) and The Aerial. Of the six balls in the top two rows, only the Ace, Jockey, and the Challenger balls have patterns that are documented in the twentieth-century literature of the game. The patterns on the other three (like many of the suspicious decorated balls in question) were purportedly produced between 1900 and 1920, but I am not aware of any 20th-century literature or verifiable examples made during that time that documents their existence.

Upon receipt of these six questionable balls, the first thing I did was bounce each of them to determine if the ball was a solid gutta percha or an early rubber core ball given that testing by sound is the quickest and easiest way to begin to ascertain that answer. Not one made the expected clicking sound consistent with gutta percha. However, all of the other pre-1920’s genuine balls shown in the lower six rows did. Consequently, to better understand the nature of those six balls, and the genuine balls below them, I had them all x-rayed as demonstrated on the corresponding image above left.

Let me begin with some of my impressions about the genuine balls in the lower four rows: The first two balls in the next to bottom row and the first two balls in the bottom row, are solid gutty percha, although the middle ball in the bottom right is a heavily deteriorated 1890s mesh gutty ball.

The third ball to the right in the next to bottom row is a 1913 Wright & Ditson Blue Circle rubber core ball with a large piece of its gutta percha cover missing on its right-hand side. The third ball to the right in the bottom row is an 1889 Eclipse—a solid composition ball that uses gutta percha mixed with other material. All the other balls have rubber cores and either gutta percha or balata covers. The whiter the core in the x-ray, the denser the material.

In each image above, a star “Patent Challenger” and a star “The Challenger” are the first two balls in the fourth row from the top. As shown by the x-ray, they have different core sizes. According to the May 24, 1912, issue of Golf Illustrated (UK), there were four different star Challenger balls, and the Patent Challenger was designed to be “full sized and weighted [italics mine].” The core is where a ballmaker could vary the weight the easiest. A larger core that is denser than the surrounding winding, as shown in the x-ray, would make the ball heavier.

As shown above, the recently painted red challenger bramble in the middle of the second row and the Kempshall Arlington ball in the fourth row have cores that are not as dense as the cores in the other rubber core balls. The core in the Arlington ball is advertised in the April 23, 1903, issue of Golf Illustrated (UK) as something special:

“The Kempshall ‘Arlington’ Ball embodies the carefully tested results of much study and experimenting, and is made upon a totally different principle compared to any other ball. The core is composed of a highly flexible centre, over which is drawn a flexible sheeting. The cover is of a specially resilient gutta-percha, which it is practically impossible to break or cut…”

I do not know anything about the core material in the red Challenger bramble.

Returning to the six balls in the top two rows, each made a muted sound when bounced which is not consistent with early gutta-percha-covered rubber cores. From the x-ray, however, I could see that they all had wound rubber cores that were consistent with the other genuine early rubber core balls in this x-ray. Note: I also x-rayed other decorated balls whose x-ray’s confirmed that the decorated rubber-core-era balls were made with rubber core centers and the decorated gutty era balls were made from solid gutta percha, so those fundamentals were correct.

As I became more invasive in my study, it became clear to me that more and more of these decorated balls had old rubber cores but modern covers. As mentioned in 1.2, recovered golf balls were produced in large numbers during the early 20th century, and it remains a relatively simple process to tear a cover off an old golf ball and install a new one. For a more detailed accounting, see 3.3 The Aerial.

It should be noted that not all pre-1920 rubber core golf balls sound the same. I have bounced a few that sounded quite muted, unlike the typical pre-1920 rubber core ball. A number of lattice pattern balls made in the 1920s and 1930s, however, will sound more like rubber. Even so, I found it significant that, when bounced, none of the six decorated balls in the top two rows above sounded like a typical pre-1920 golf ball with a cover made from gutta percha or a gutta percha compound.

One thing this written article cannot sufficiently convey is the sound made by the different antique golf balls and their components. To fill that void, I have prepared these videos so people can hear the different sounds made by various balls and their components for themselves.

Sound, however, is only a small part of the wide spectrum of information and elements that are presented in this report. Because the videos are supplementary, they do not need to be watched before reading the rest of this report. The stories and images are where the full sum and substance of these decorated balls is found.

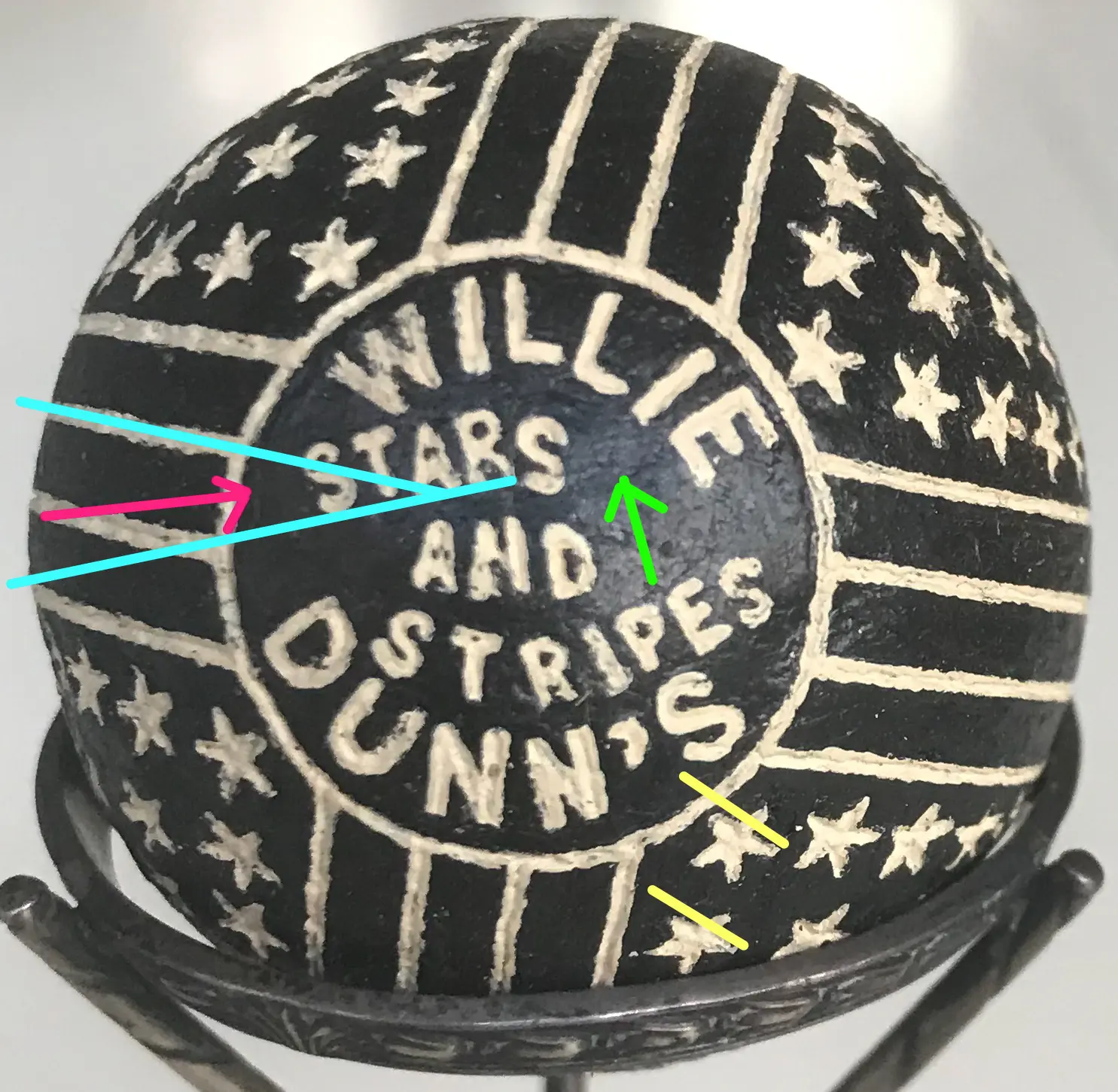

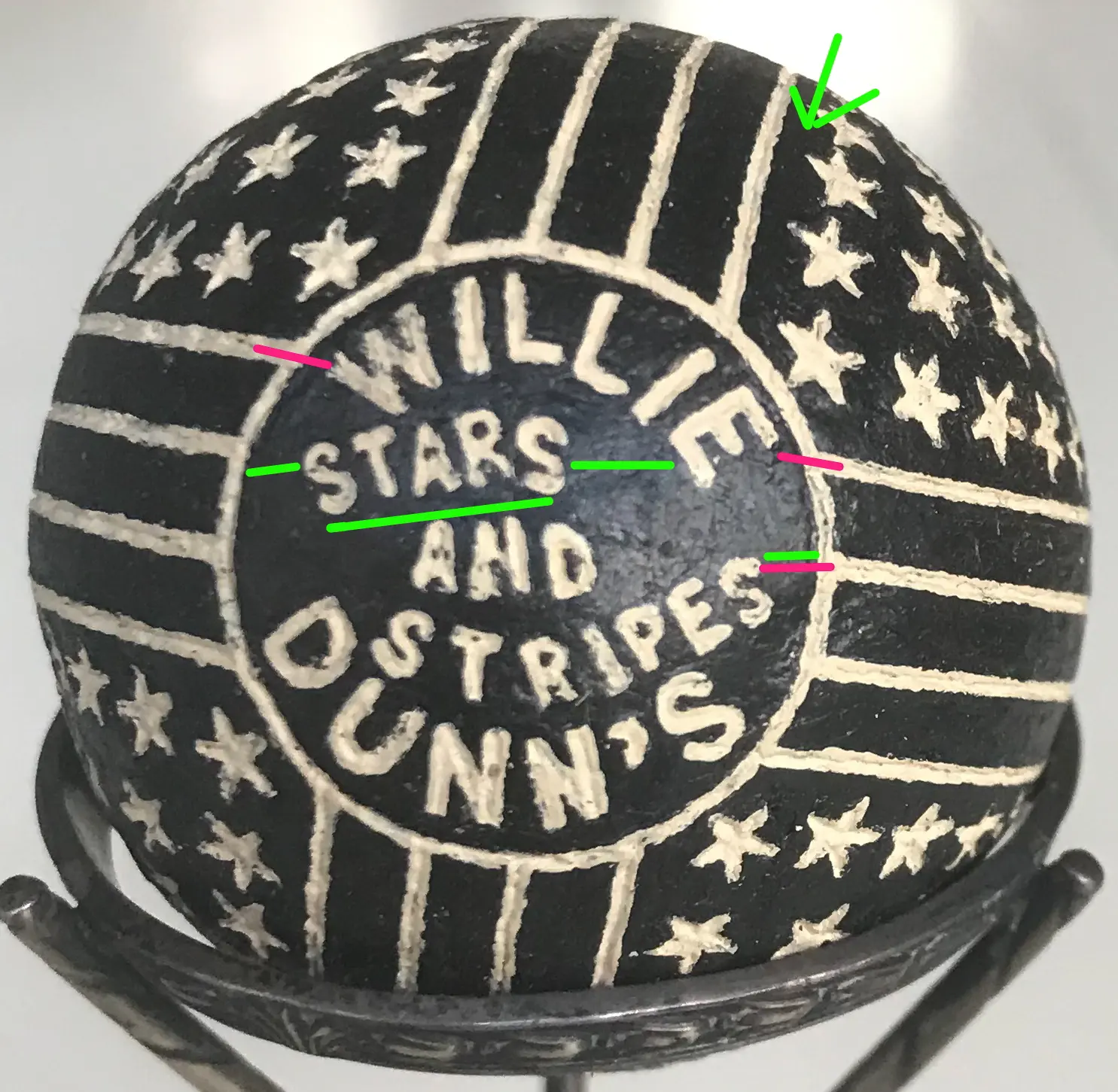

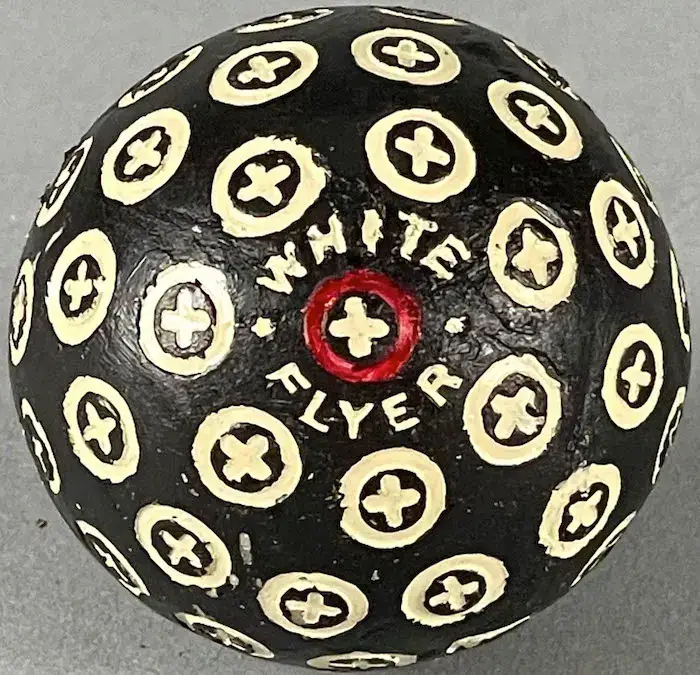

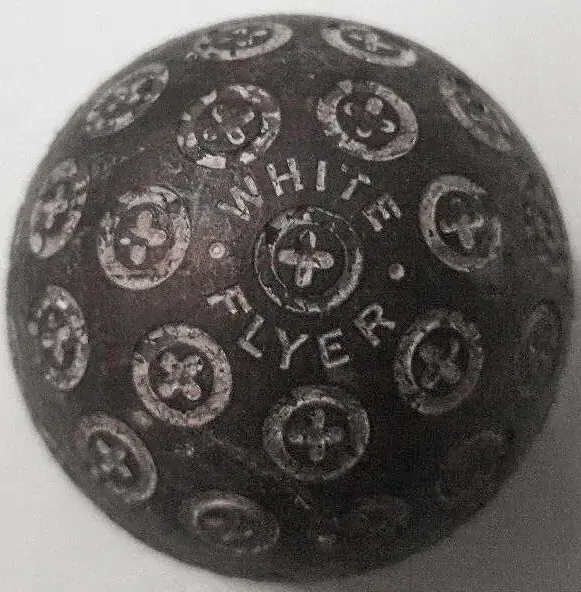

The genuine white Willie Dunn’s stars and stripes (Image 1), shown above in its original white paint, was patented in 1897. The black painted ball (Image 2) is different. The gap between the start and end of the word “Stars” is different between both balls. The angle of the word stars is different between both balls.

The circle, letters, black stripes, and white stars on the black ball are larger than they are on the white ball. It’s as if a 2-D image was scanned into a CAD program and then enlarged so it could be output as a stencil/template that would cover half of an actual ball, the surface area of half a ball being much larger than it is on an image of half a ball. Given an overlaid template or stencil, most anything can be traced/engraved and look more or less like the original, although tracing/engraving is much harder to execute on a curved surface and there will typically be slight variations from one to the next.

“Oversized name badges” larger than the name badges on original examples are also found on the following additional decorated balls: Henley 2.9, Bruce 3.1, Vaile 3.2, Shamrock 3.9, PG 4.3, and Resiliant 4.12. Genuine examples of those seven balls and the Stars and Stripes are among the most valuable, unusual, and rarest balls that exist. All eight balls are quite expensive to buy if, and that’s a big if, you can locate one. Images, however, are exponentially easier to find and download.

Above (Image 2), we see the same picture of the black stars and stripes ball presented earlier, this time next to a different black stars and stripes ball (image 3). The difference in the size of their center circles are not the only differences between the two balls.

The red lines draw attention to the difference in location where the “W” and “E” in “Willie” and the “S” at the end of “Stripes” are found, in relationship to the line closest to each letter.

The green lines call attention to the different spacing at ends of the word “Stars” as well as the different lengths of the word itself.

A green arrow at the top of each ball calls attention to the difference in spacing between the line and the stars.

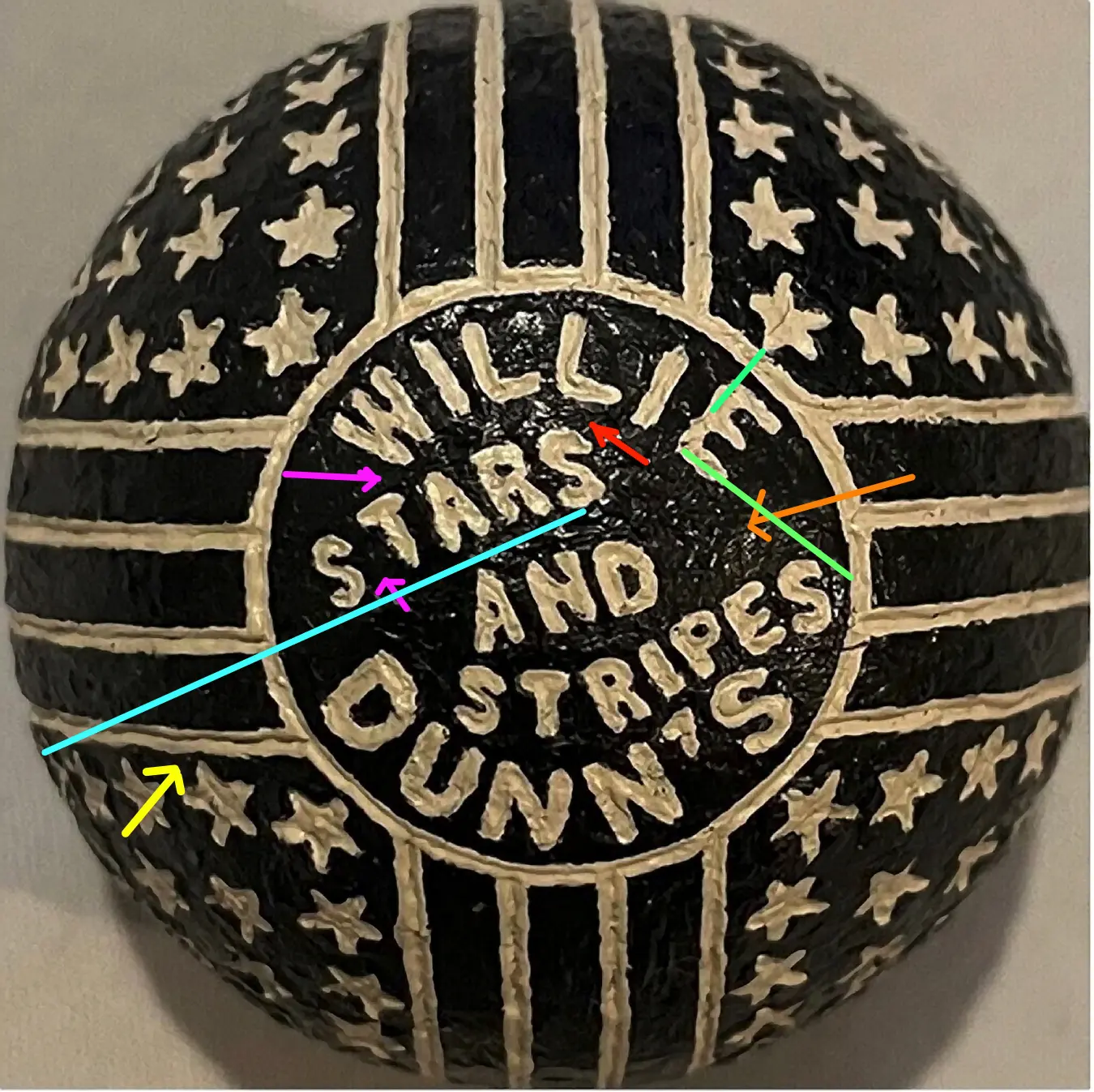

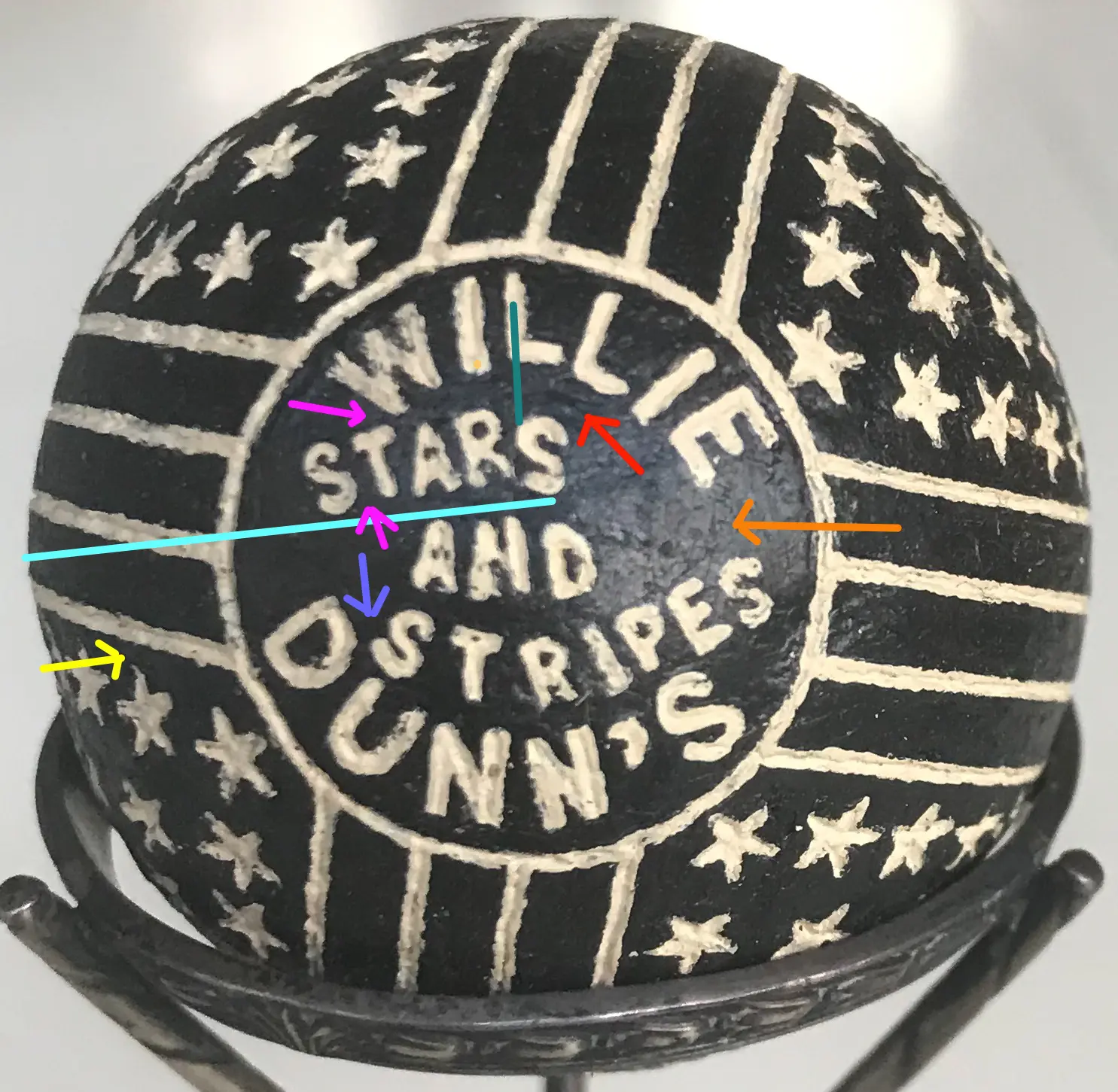

A third black Stars and Stripes is shown here (Image 4), along with the prior two pictures of black balls for easy reference and

comparison (Image 2 and Image 3)

I have drawn various color matching lines on each of the covers to point out differences between the three balls, none of which have patterns

that match. They each have unique differences that set them apart from each other and it goes beyond the painting.

Stars and Stripes balls are marked with their patent number on their opposite pole, not their name. Hence, it’s clear that the three balls above are separate and distinct, and one ball is not shown twice.

In short, none of these three recently painted black Stars & Stripes balls have an identical pattern. Many anomalies become apparent when one takes the time to make close comparisons. In the images above, I have used colored lines to mark anomalies that are unique to each ball. These anomalies indicate to me that either:

Below a genuine Stars and Stripes ball in its original white paint is positioned directly above one of the black painted Stars and Stripes.

Matching in distance side to side as shown, these two balls are equal in size so that the viewer can see the differences in the patterns and writing between the two balls, and there are many. The more time you spend looking at the ball in its original white paint and the black Stars and Stripes balls shown, the more differences you find. For starters, the size of their name circles and printing inside do not match. The size of their stars is different as is the spacing of their stripes.

The construction of the stripes is also different. The genuine ball has straight uniform lines that are as wide as the paint that fills them. These lines were molded in place. The lines on the black ball are inconsistent, neither straight nor uniform in depth, and appear to be engraved in place and painted by hand.

Smooth gutties date to the late 1840s, the earliest days of the gutta percha golf ball. While they can be found in original red or white paint, the ball itself, in every instance that I am aware of, was made from dark black-brown gutta percha.

Red gutta percha was not quite as durable as black gutta percha. By the 1870s, red gutta percha was nevertheless being used to make the occasional patterned gutty ball.

To my eye, this ball looks like it originally had a pattern, likely a mesh pattern. Today it’s a smooth gutty, a blank canvas in a sense, and it serves as evidence of how easy it is to sand down and remove the pattern from a gutty ball.

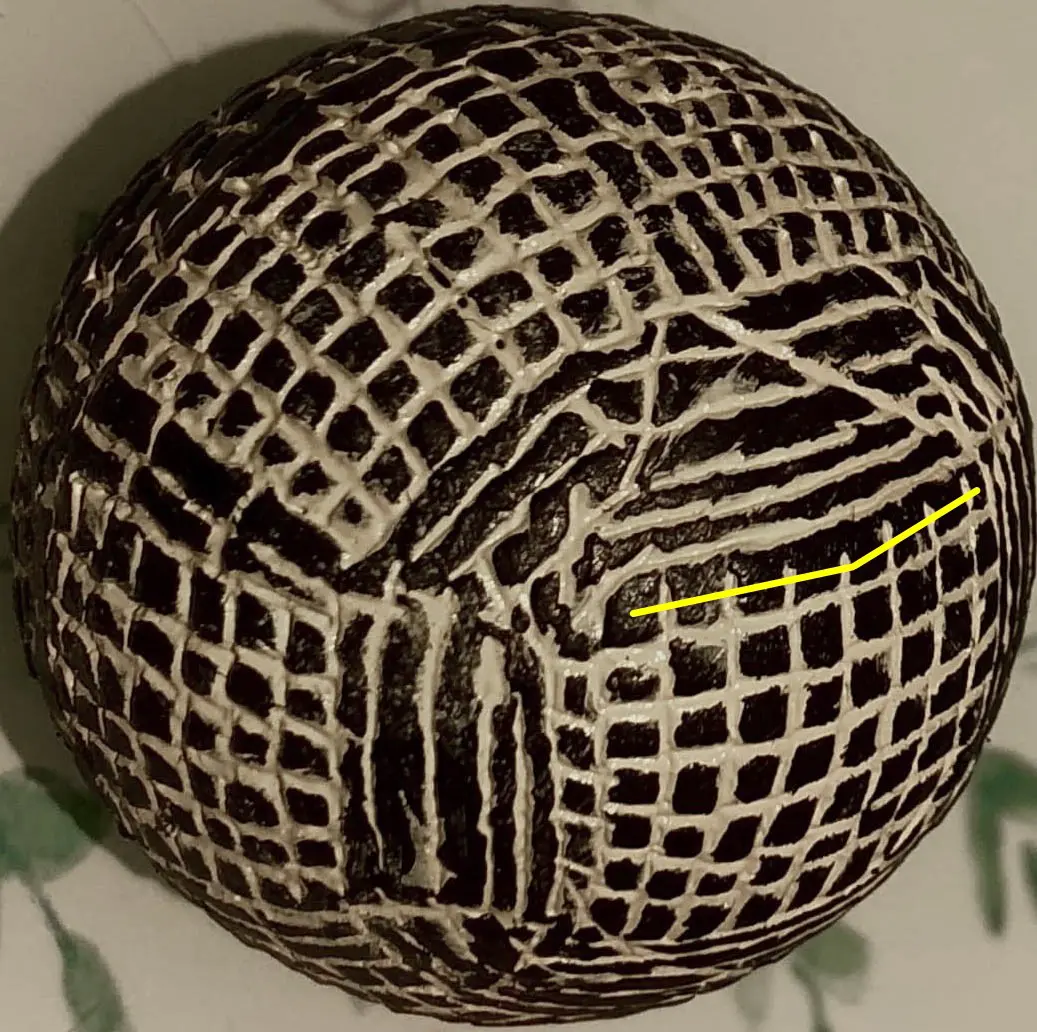

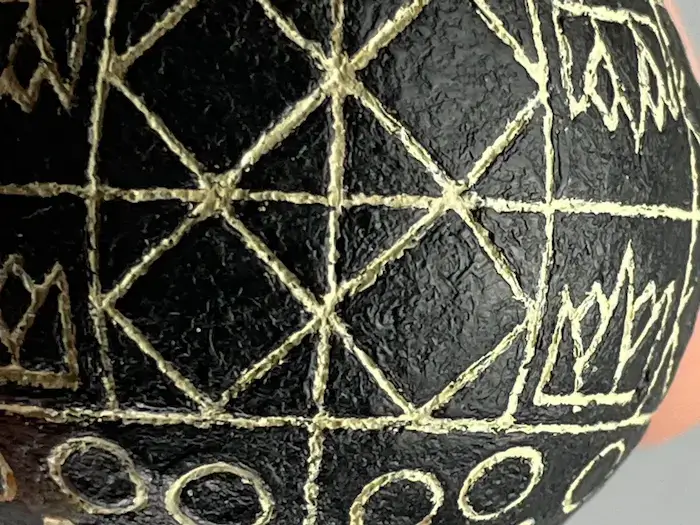

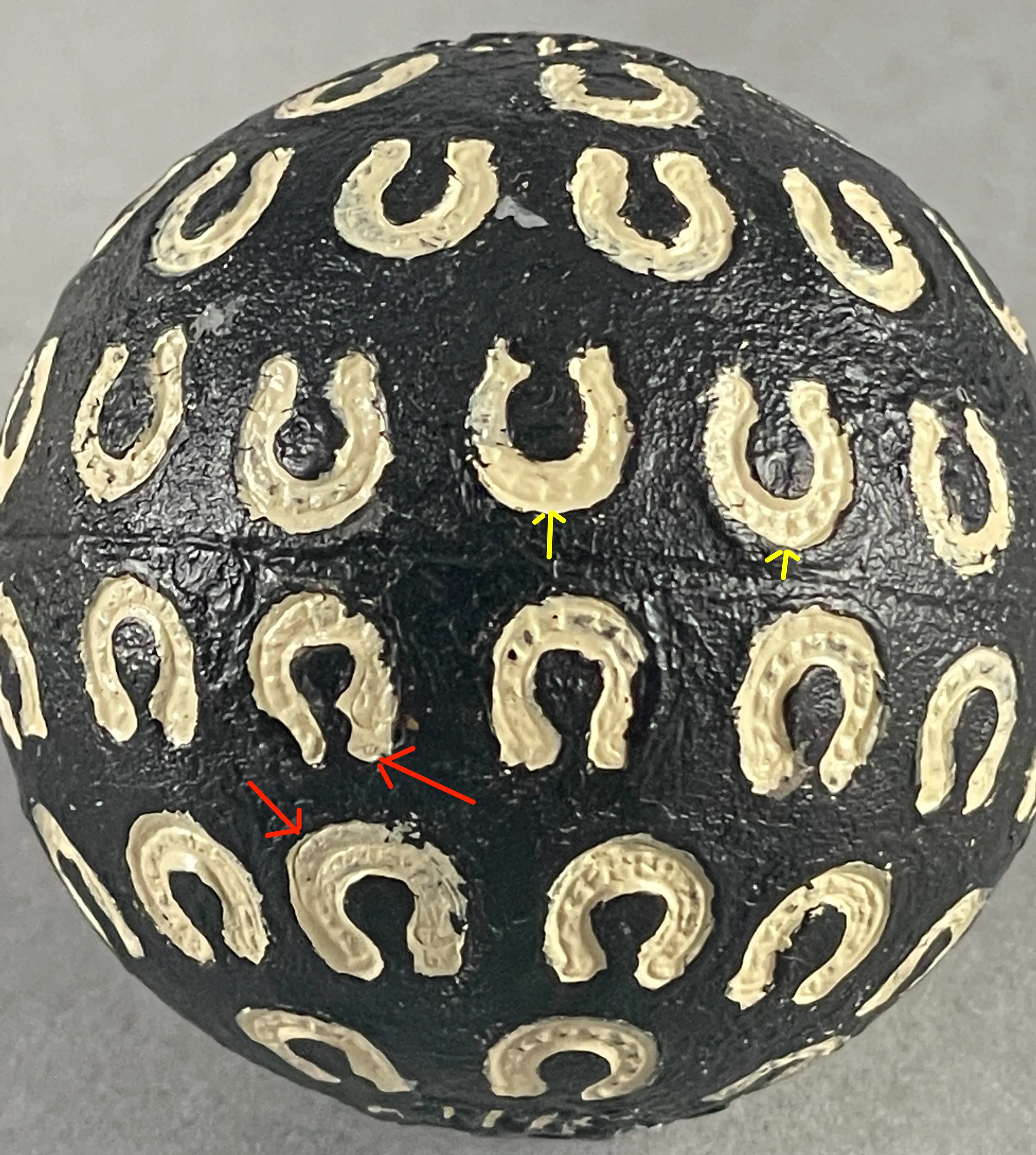

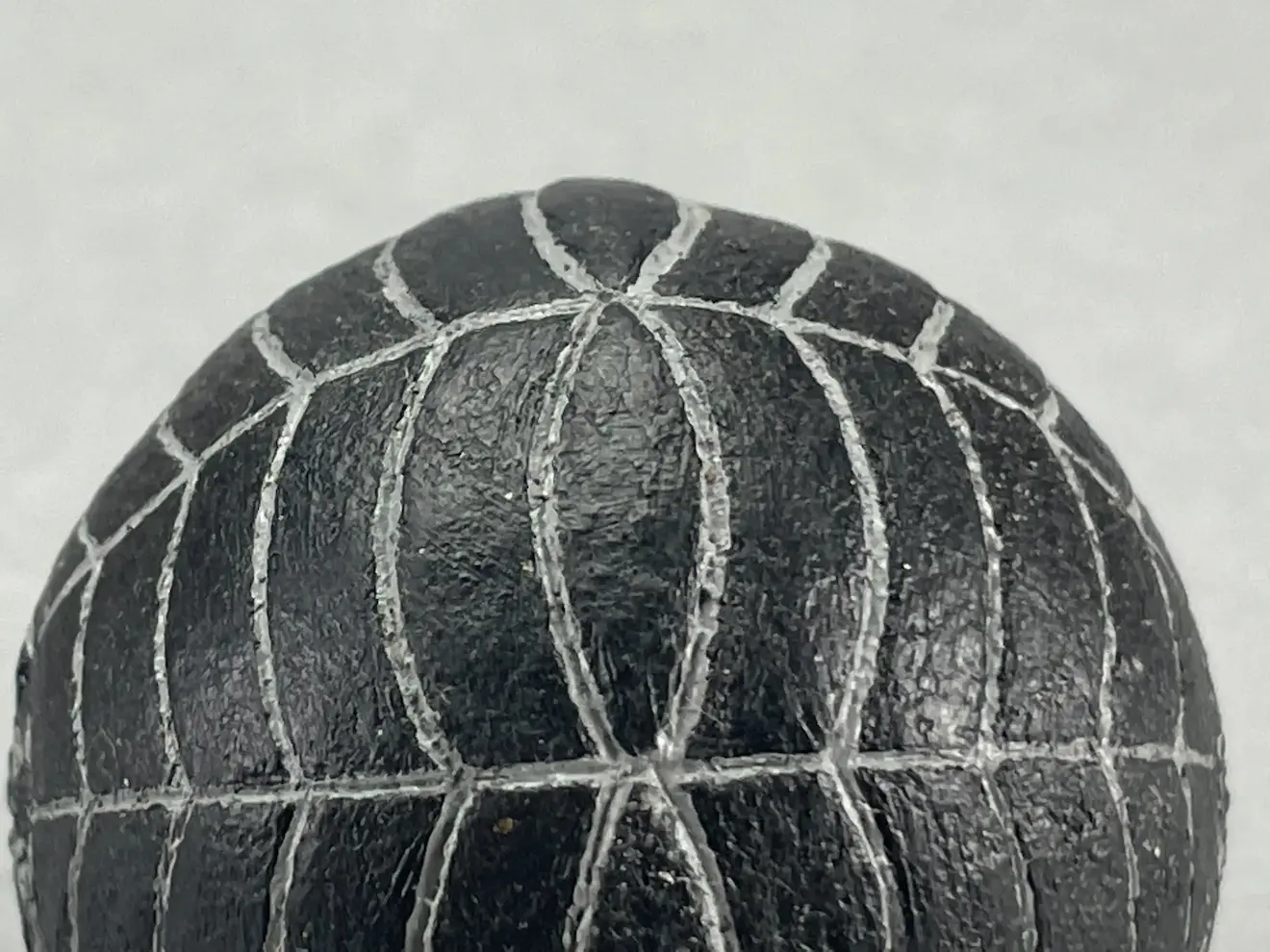

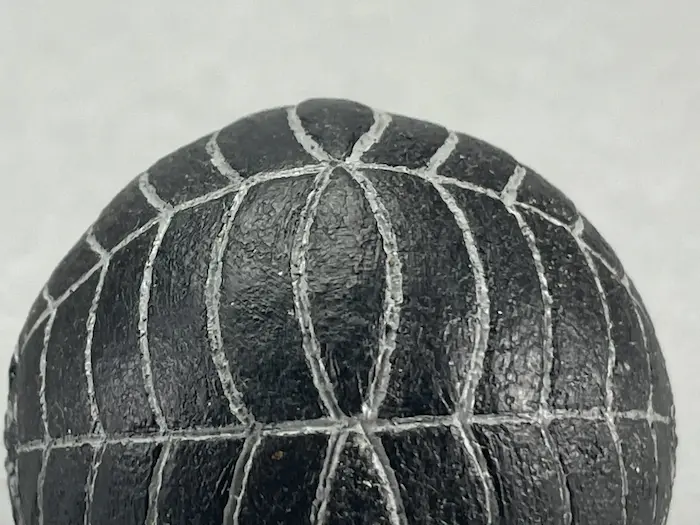

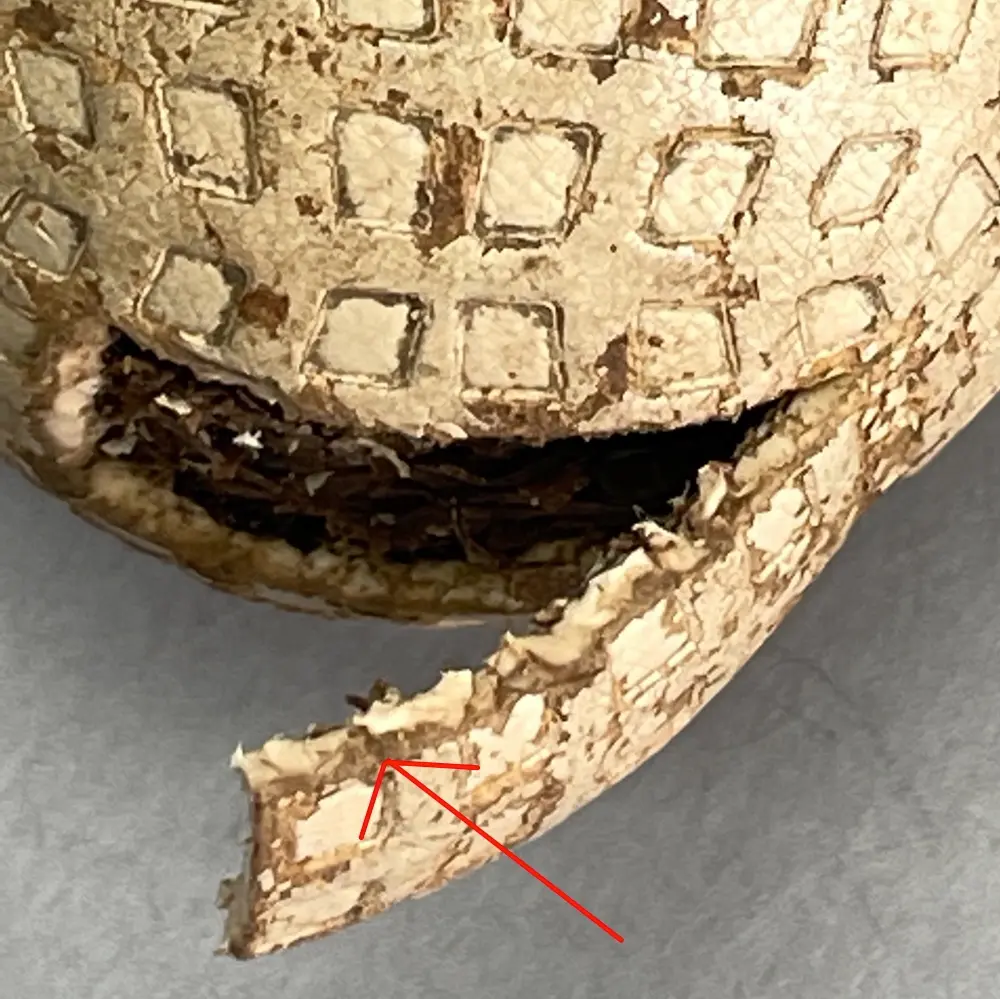

Both of the balls at the top of this segment make the sound of solid gutta percha when they are lightly bounced on a hard surface. The circa 1870s ball on the top right bears a hand-hammered pattern with some of its paint worn off and its gutta percha exposed. The ball on the left is entirely covered in modern paint—solid black with off-white “hand-hammered” lines—only the hammered lines are not consistent with the lines I have seen on genuine hand-hammered balls that still retain some or all of their original paint. Instead, they appear to be engraved. Such is also the case with the ball directly above. Many of the lines on these two black-painted balls are short, disjointed, meandering, and in some instances distinctly crooked and even “L-shaped.” They are not long like the distinctly cut lines made with a hammer claw on the ball to the right in the 2-ball image above and on the unpainted and white painted gutta percha balls at the end of this segment.

A set of lines on the poles of both black-painted balls as pictured (so far) stop identically short of the perpendicular bordering line (as shown by the yellow line below), and the lines appear engraved. Again, many are short, disjointed, and crooked.

The first image below is a third black-painted ball with a hand-hammered pattern (Image 1). To its right is a solid brown gutta percha hand-hammered ball that was never painted (Image 2). Underneath those two balls is a hand-hammered ball that is still in its original paint (Image 3). The surface of this third black ball appears to be much smoother than it does on the other two balls below. Its lines are longer, more consistent with hand hammering, but they are much shallower than they are on the unpainted and white painted hand-hammered balls shown below and the partially painted gutty ball to the right at the top of this segment.

Hand-hammering gutta percha left larger ridges as opposed to the shallow lines. These ridges are readily apparent on the unpainted and white-painted hand-hammered balls below. The squares formed by the hammering have rounded edges and appear as if they are raised.

The first image is a Vardon Flyer that has been painted gray. The tops of the brambles and the name ring have been painted black. Originally produced in 1899, the Vardon flyer is a solid gutta percha golf ball. This gray ball is also made from gutta percha. It appears solid when x-rayed and sounds like gutta percha when lightly bounced. On the right, this white Vardon flyer is in its original paint and has never been used. It is also solid gutta percha, but the two balls have major differences.

Shown side by side, the name rings are not the same. The ring on the Vardon ball in its original white paint is raised above the surrounding surfaces of the ball, and the top of the ring is flat. It was formed in a mold as were its letters. The black name ring on the gray/black painted ball is not raised. The ring is simply painted on the undulating surface of the ball, and the Vardon Flyer name appears to be etched in place, lacking the evenness and width of the letters found in the molded Vardon name shown.

This image better shows the bumps under the letters engraved in the black-painted ring. For starters, notice how the “Y” is elevated above the neighboring “E,” etc.

Two more black-painted balls with pole lettering anomalies follow.

The letters in the “Mungo Park Jr” stamp do not appear to be flat. Instead, they appear to be painted/installed on an undulating surface. The names on antique golf balls were typically installed on flat, smooth surfaces. The lettering on this pole is not consistent with molded lettering.

The spacing of the letters on this JH Taylor ball is uneven. The “H” is much closer to the center dot than the “J”. The “H” is also closer to the inside of the name circle, while the other letters are closer to the outside of the circle. The letters “OR” are closer than the closest parts of the letters “YL”. The “28” in the center is not centered either vertically or horizontally. This is not consistent with the work of a late 19th-century ballmaker.

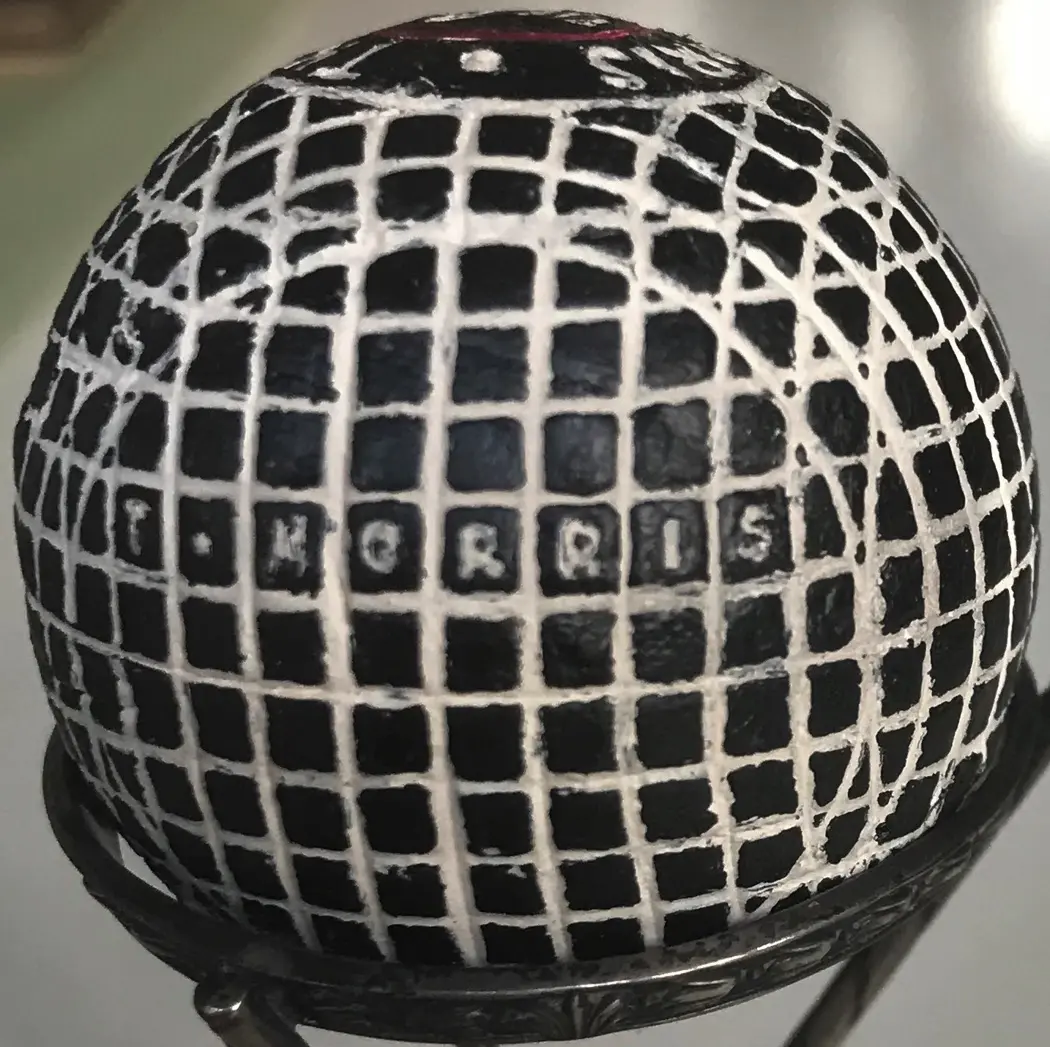

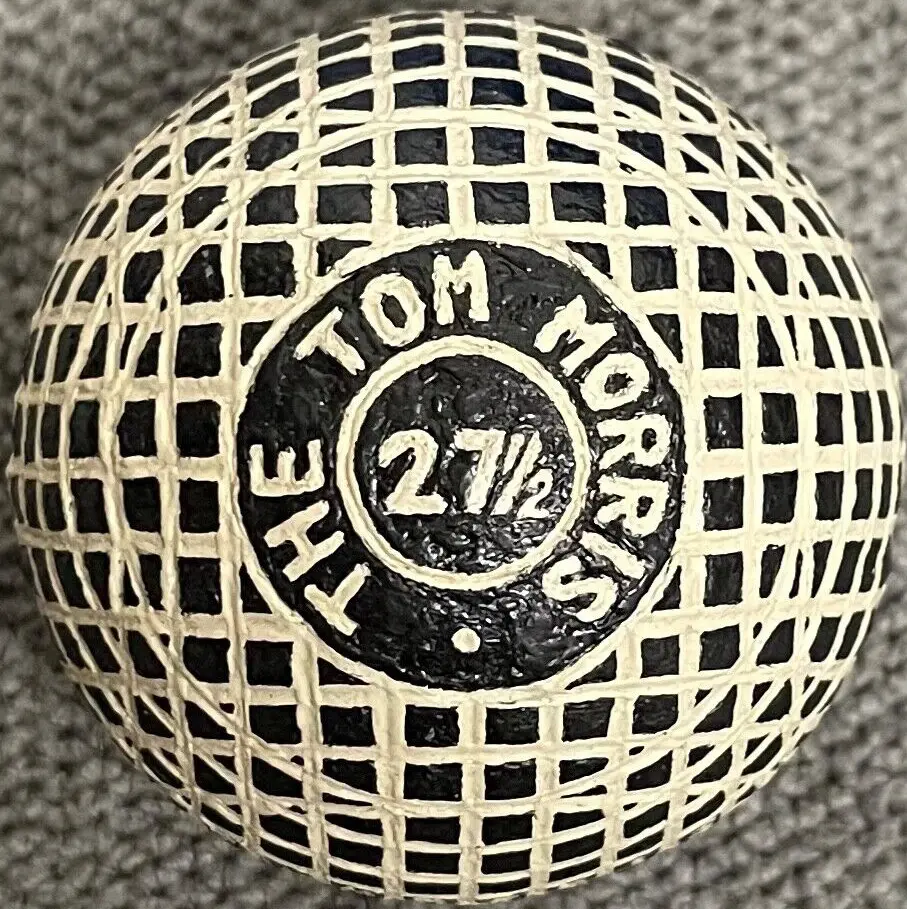

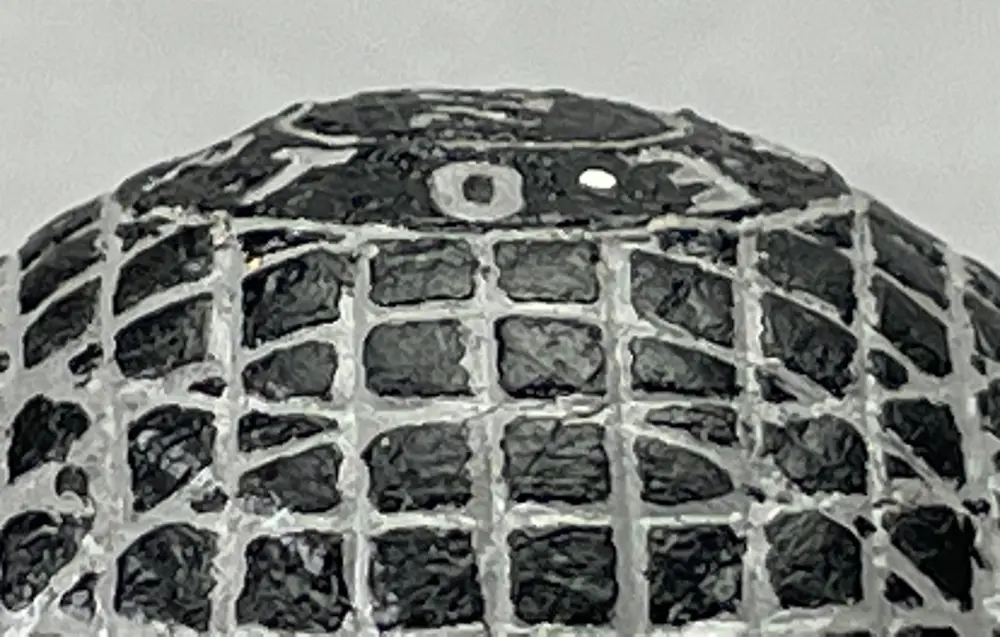

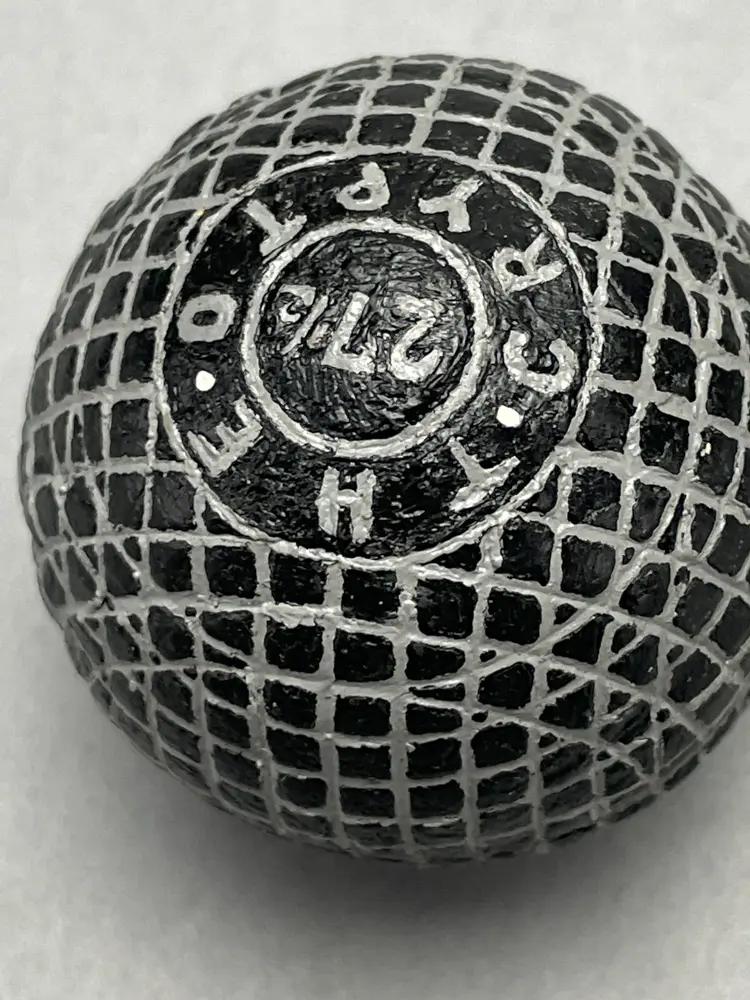

With all the black and white paint on its cover, there is nothing that proves the “Tom Morris” name is original to the ball. One can’t tell if the lettering is molded or not. All the white paint obscures the letters, and they could be engraved. The fact that this ball does not have clear, uniform molded letters sunk into its surface—which is how every named gutty ball of this design was made— is not good. But since the ball has obviously been hand-painted in recent years, a person could carefully strip off the paint and restore the ball to its original, unpainted gutta percha.

Not only do unpainted gutty balls bring prices comparable to original painted examples (all other things being equal), but they are also worth far more than repainted ones. It makes no sense to put modern paint on a genuine gutta percha ball, a ball that is already dark brown let alone one that bears the name of Tom Morris. Doing so would conceal if not lose key elements of its historical value. Then again, if stripping the paint off this ball reveals “Tom Morris” is etched in place and not molded, what does that tell us about the ball?

Because this entire ball is painted with modern paint, there is no way to know if the name stamped on the side is old or recently stamped in place. Anybody can stamp a ball and then paint it. This ball is the mesh gutty ball shown two pictures above, stamped “The Tom Morris 27 ½” on the pole.

Next, let's compare these four images. The first (Image 1) is the same Tom Morris ball shown earlier. Next is a second black-painted Tom Morris ball (Image 2). The other two images are the left (Image 3) and right (Image 4) poles of a third black Morris ball.

These three balls have notable differences. In Image 2, the ball has a larger “name badge” on its pole when compared to the other two balls. Because of that there are only three circular rings between the badge and the equator, as shown in the image. Because the other two balls have smaller badges, there are four circular rings between the badge and the equator.

In addition, some of the letters do not match up. Red lines have been inserted to show a few specific areas where the locations of the letters are different. On the ball in Image 2, a red line has been inserted to show how the “M” in Tom is in a different location from the same letter on the other two balls. The “T” in Tom on the balls in Image 1 and 3 are off, as is the “RR” and “IS.” The “H” in image 3 is in a different location than it is in images 1 and 2. The distance between the “T” and “H” in “The” in images 1 and 2 is not consistent with the spacing of said letters on either pole of the ball in Images 3 and 4.

Not just the spacing between some of the letters is off, so is their orientation. Two examples are the “RR” in “Morris” on the balls in Image 1 and Image 2. The space between the bottom of those letters on both balls is roughly the same, but the ball in Image 3 has a much larger gap between the top of the letters than 1. In like manner, ball 1 has a large gap between the top of the “IS” and ball 3 does not.

Next up is an image of a bramble ball marked “Tom Morris.” The “T” and “O” in “Tom” are quite close together and apart from the “M.” Also, the

TO is oriented in one direction and the M in another. Plus the “IS” in “Morris” is off.

It looks like white paint was stripped off the cover. The cover itself, however, is not consistent with a typical c.1900 gutta percha cover

(bramble balls were popular during the late 1890s and early 1900s). It is not dark brown like the overwhelming majority of covers used on early

rubber core golf balls. Furthermore, to my eye, this cover looks like it is made from rubber. It does not have the depth or “plastic” look that

a gutta percha cover in the same unused condition will have. While this cover stripped of its paint does not match up well with typical c.1900

bramble ball covers (see below), it’s rubbery look and color fits in well with the stripped portion of the covers on the heavily painted

decorated bramble balls shown below.

The two W. Park Jr. 27 ½ balls above, while they initially might look alike, have major differences. The first ball (Image 1) has five vertical and horizontal lines in the center section while the second ball (Image 2) has only four vertical and horizontal lines in the center section. In addition, the width of their name rings is different, not to mention the spacing issues with the lettering on both balls. I believe both balls, however, are made from gutta percha. But, again, because these balls are heavily painted and their lettering is not consistent with molded lettering (the “27” on the ball in Image 1 has obviously been engraved), nothing remains to prove that these balls have not been modified.

It would not be beyond the realm of possibility to take either of the solid gutty balls below, made originally with no name, and engrave it “W. Disney World.” Next just paint away and done. If the ball below left were to be modified, possibly the trickiest part would be to make an inner circle for the name ring as neat and clean/symmetrical as its existing outer circle.

It is worth noting that the ball on the right has a raised name ring at each pole, although the ring is not marked with any names. The ring needed to be at the same height as the top of the mesh squares so the ball would roll correctly. In addition, the top of the ring needed to be smooth, so the letters of the name (if the ball was to include a name) would be clean and sharp, and easily accomplished during the molding process.

Note: other solid gutty balls similar to the ones below were made without names.

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary (merriam-webster.com/dictionary/crypto), the word “crypto” was not used as a noun until 1940. It was used as an adjective, meaning, “not openly avowed or declared—often used in combination: crypto-fascist” beginning in 1681. Consequently, a solid gutta percha ball with a name that made no sense would not be enticing to the market in the 1890s.

However, the interest in a one-of-a-kind 125-year-old ball bearing a name that is all the rage in the investment world today would be quite different.

When viewing the name on the pole above, one can see that the surface around the letter “P” on the left-hand side curves inward a tiny bit. These small depressions or flat areas exist with some of the other letters, but they can be hard to see unless viewed close up from just the right angle. The numbered top of the pole appears uneven as well.

Simply put, the pole on the ball shown above is not consistent with the poles on the three named 1890s gutty balls of the same design (Argus, Paragon, and Ocobo) shown below. The first two of these balls still display their original paint. The third has an unpainted gutta percha surface but with gold-painted lines. Painting just the lines preserves the authenticity of this ball. The dark brown gutta percha is clearly on display, and there is no evidence of sanding or engraving around the lettering.

Directly above is the other pole of The Crypto. The “H in “THE” is on a different plane/angle than the “T”, and the “E” is on a different plane of its own. This is evidence that the original letters were sanded off the ball and new letters installed. The lettering on the prior three balls shown above are all on the same plane.

The lettering on this pole is not uniformly level because the pole under the lettering is not uniformly curved. If you take time and study the letters, their undulations become more obvious as does the poor spacing in the word Crypto. The “O” is off on its own, etc. To my eye, this ball has been doctored.

When a ball has been repainted in recent years, anything could be underneath the paint—filler, a sanded surface, remains of a different pattern/name, or even a new 21st-century cover. Black paint and fresh white engraving hide the original impression of the letters and pattern made by the mold, so those things are no longer available for inspection. They have been destroyed. Why do that to a genuine antique ball?

For the record, I have never seen any reference to a Crypto ball in either the 19th or 20th-century literature of the game, nor have I ever seen or heard of such a ball that was not painted black.

The what? … The “Colonal”??

And so, we come from a black ball bearing a name that made no sense in the 1890s to a black ball with an engraved title that was never a word! As shown above with red and blue lines, this ball has spacing inconsistencies that are not typical for an early 19th-century ballmaker.

Given that all the letters are deep and strong, the paint could be removed from the ball. After all, antique golf balls covered in modern paint are worth much less that the same ball in its original painted or unpainted condition, all other things being equal. Besides, it’s not like the ball can’t be repainted if a modern paint job, for whatever reason, is preferred. Then again, given the modern black paint, misspelled name, asymmetrical spacing and etched letters, it’s a good bet that the cover of this ball would be found sorely lacking in authenticity if the paint were to be removed.

For the record, I have never seen any reference to a Colonal ball in either the 19th or 20th-literature of the game nor have I ever seen or heard of any ball with a misspelled name that was not painted black.

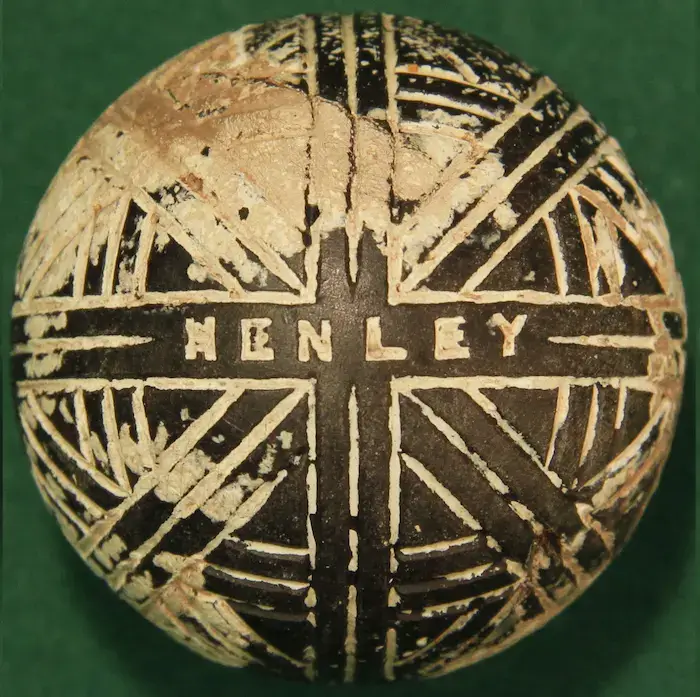

The two black Henley balls above (Image 1 and Image 3) are shown next to two Henley balls that still retain various amounts of their original white paint. It’s easy to see that both the Henley name and the stripes on the black Henley balls are much bigger than they are on the Henley balls that still retain much of their original white paint. In addition, the lines on the black-painted Henleys are not consistent with the lines on the genuine Henleys in their original white paint.

Notice that all the Henleys in their original red or white paint in this section have the same smaller lettering and closer lines, and gutta percha is visible where the paint is worn or chipped. Henley “Union Jack” pattern balls were made from solid gutta percha in 1895. For more on name/pattern size differences, see 2.1 Stars & Stripes.

Directly below is a close-up of a genuine mint Henley in its white paint. Upon close inspection, the crazing in the original paint can be seen. Directly below it is another black Henley. This one has the correct size letters, or so it appears. I believe this is a gutta percha ball, only all the black and gold paint makes the ball impossible to vet in its current condition.

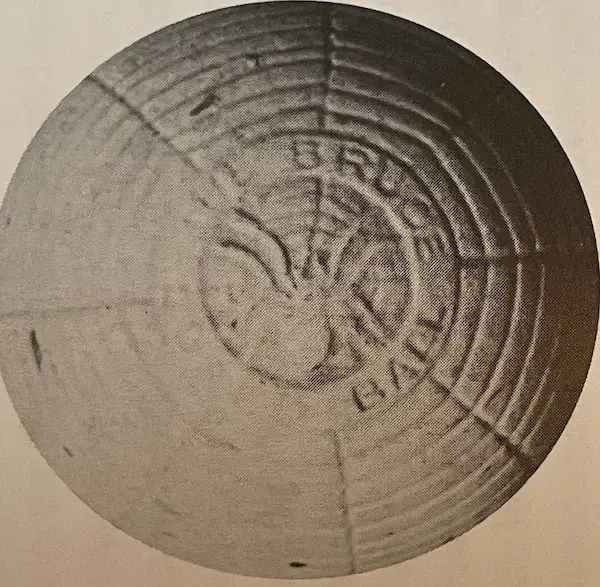

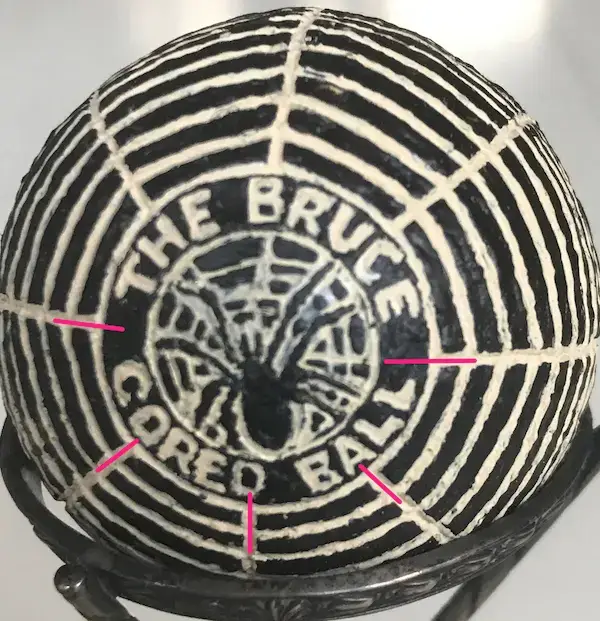

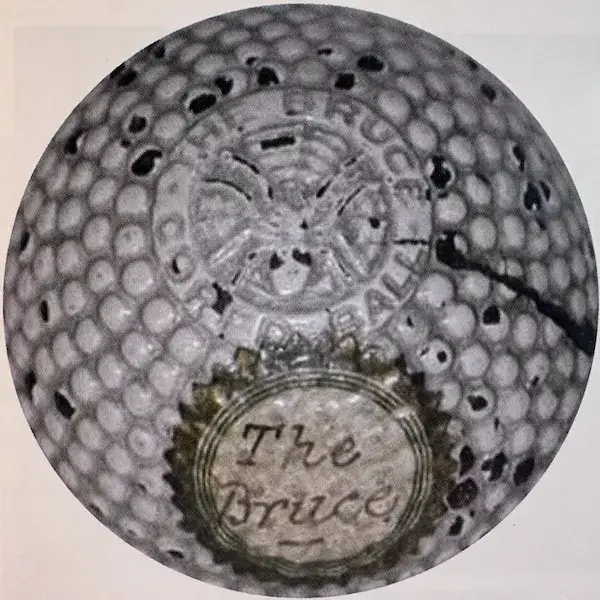

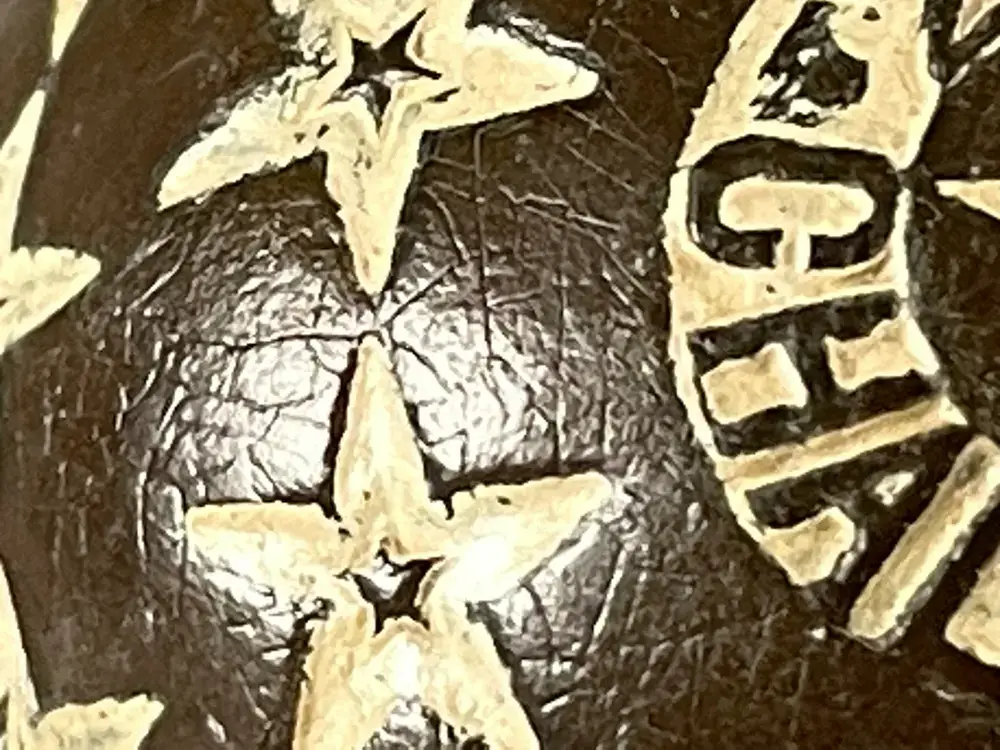

The two white Bruce Cored Balls were made in 1904. The black-painted ball is clearly different. On the white balls, the spider is in relief—raised up. On the black ball, it is simply engraved into the surface. Also, on the black ball the shape of the spider’s body and legs is different, the circular ring around the spider is bigger, it’s lettering is bigger, and its web is not as tight, etc. (For more on such name/pattern size differences, see 2.1 Stars & Stripes.) Also note: On the white balls the web pattern inside the name circle is recessed. On the black ball, it is not.

These two black-painted Bruce Cored balls are different from each other. The red marks call attention to the relationship between the perpendicular lines that extend out from the name circle and the letters inside the circle. Notice how the “H” and “B” letters under the lines at the top of the circle are in the same location on the two balls. However, when you compare the letters to the other lines around the circle, as shown by the red marks, the letters are in different locations.

The web pattern inside the two name circles is decidedly different, as is the body of the spider. Also different is the size of the name circle itself. The amount of space above and below the letters on one ball is different from the other. Only one ball has spacing dimples in the name circle.

When compared to the two original white Bruce Cored ball shown earlier, the spider on both black balls is engraved in place, not raised up in relief, and the web pattern inside the name circle is not recessed.

Again, neither of the black balls above match each other nor do they match the genuine white Bruce Cored balls shown earlier, both of which do match.

Moving on, the modern painted black and yellow Bruce Cored bramble ball below is not consistent with the second Bruce Cored bramble ball in its original white paint. The differences between the two balls are many and easy to see. This second ball is a genuine Bruce Cored ball from the Harry B. Wood Collection assembled early in the 20th century.

The imposter ball is quite different from the genuine ball. The name ring is thicker. It is not elevated to the height of the brambles. The lettering is much larger. The spider and web do not match in shape or elevation. The name ring, the spider, and the web on the yellow/black painted ball, however, are a much closer match to the spiders and webs and name rings on the poles of the other two decorated black Bruce Cored Balls shown earlier.

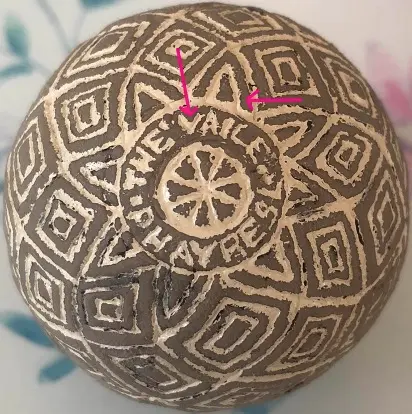

In 1909, Percy Vaile received a British registered design for his Vaile golf ball cover pattern. The first ball—beige colored (Image 1 & Image 3)—is marked “The Vaile, F.H. Ayres,” although it is difficult to read. The second ball (Image 2 & Image 4) is a The Vaile ball still in its original paint. The lines on the beige-colored ball are not consistent with the lines on the ball in its original paint. They are deeper, disjointed, and create larger diamonds. The execution of the pattern on the beige ball is not consistent with the pattern on the ball in its original paint. The name circle on the beige ball is larger and the spokes inside it are small when compared to the ball in its original paint. (For more on such name/pattern size differences, see 2.1 Stars & Stripes.)

Genuine Vaile balls were made with gutta percha covers. The dark gutta percha can be seen where the paint has been chipped on the painted Vaile ball.

Because the beige ball is only painted in its lines, it is easy to view its cover material, which is not consistent with gutta percha in its color or texture when compared to a typical gutta percha cover. When the beige Vaile ball is bounced it sounds muted. It also feels somewhat tacky when handled. Gutta-percha-covered balls typically give off a distinctly resonant click when bounced, and they feel sleek and solid when touched.

Both the Vaile and Aerial balls in the image above are unpainted and appear to be made of the same material, but not gutta percha.

Above right is a second unpainted-except-for-its-lines F.A. Vaile ball. Red arrows show inconsistencies in the lettering and pattern size between the two balls directly above as do the different sizes of the name rings and inner spokes. Not only are the patterns different between these two balls, they are also inconsistent on each ball. Their covers appear different in color and texture. The cover on the beige ball does not appear to be as smooth as it appears on the brown ball. In addition, the letters and lines on both balls above are consistent with hand engraving, although the material engraved (especially in the unpainted beige Vaile and Arial balls) does not appear to engrave well.

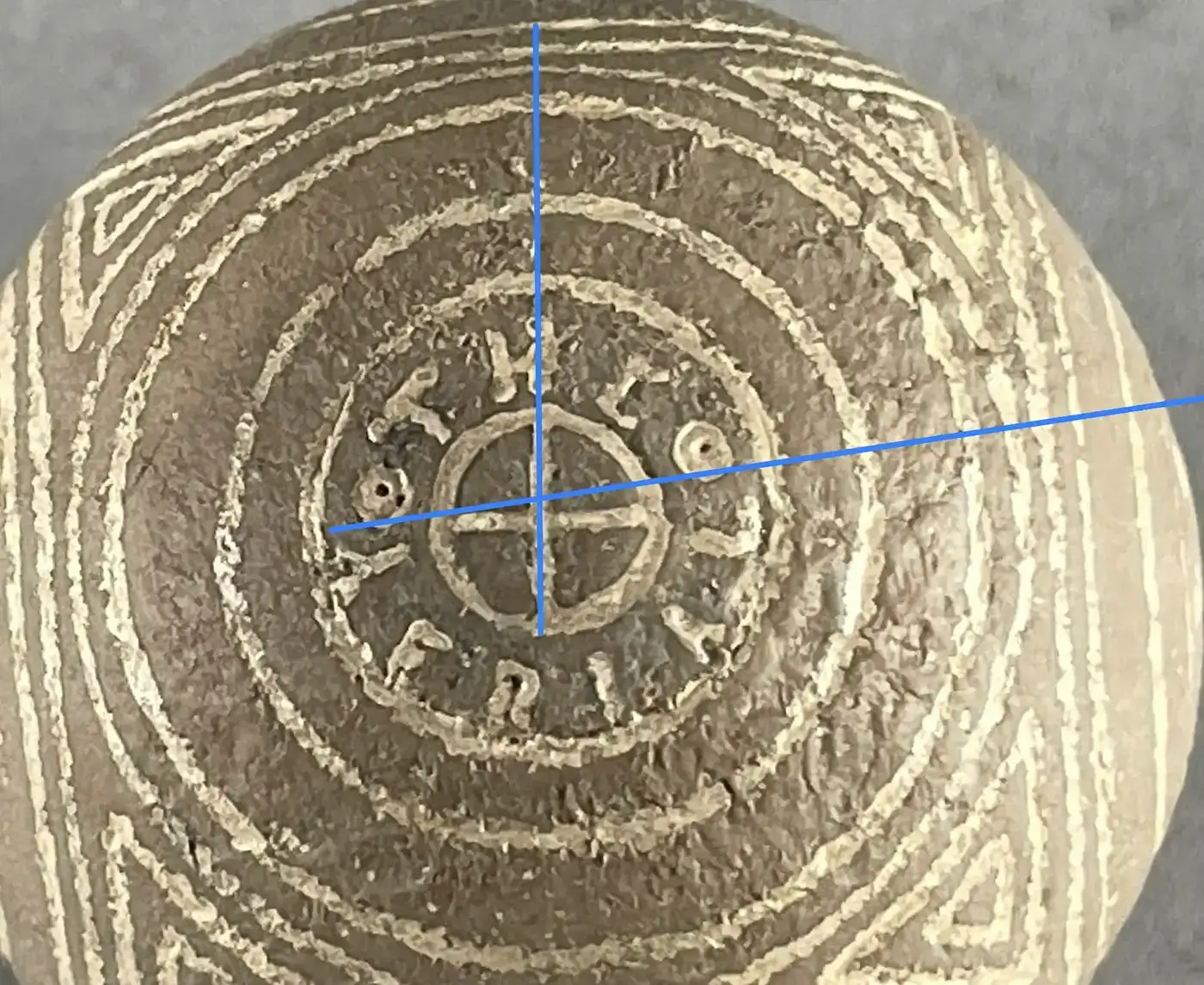

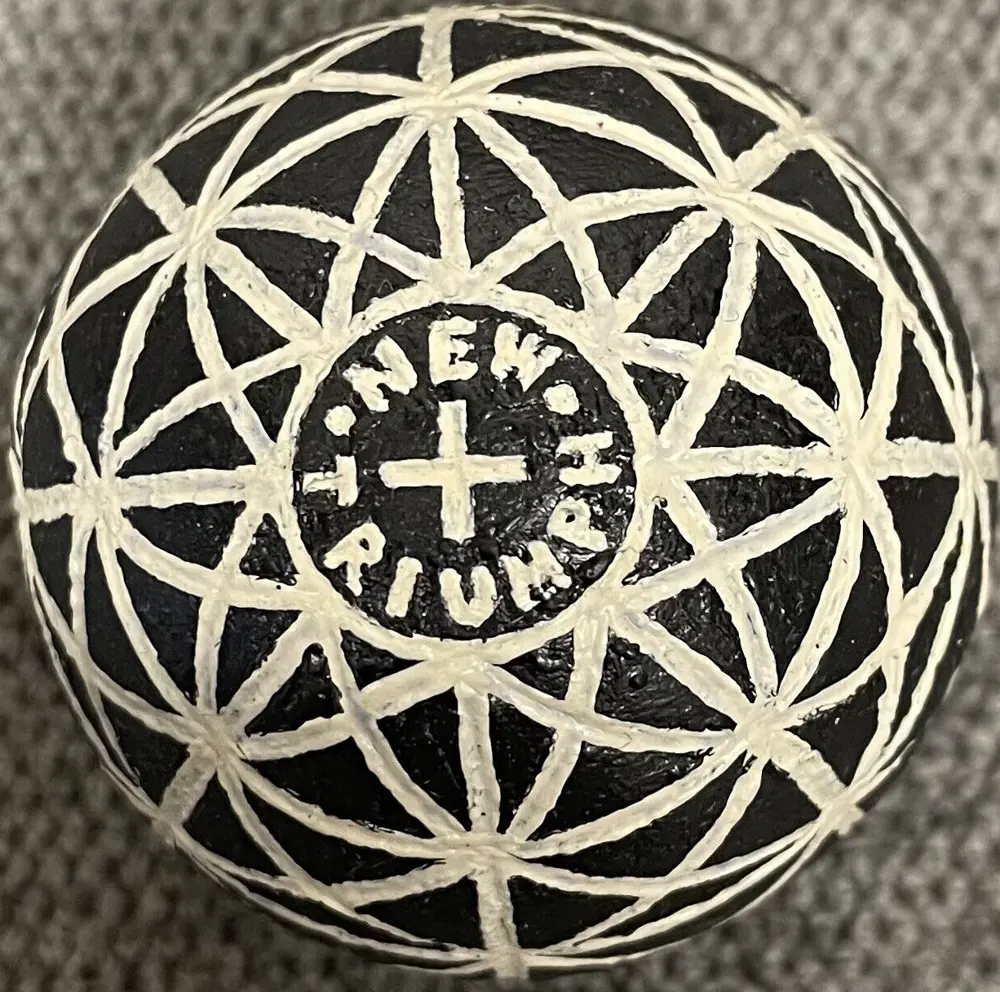

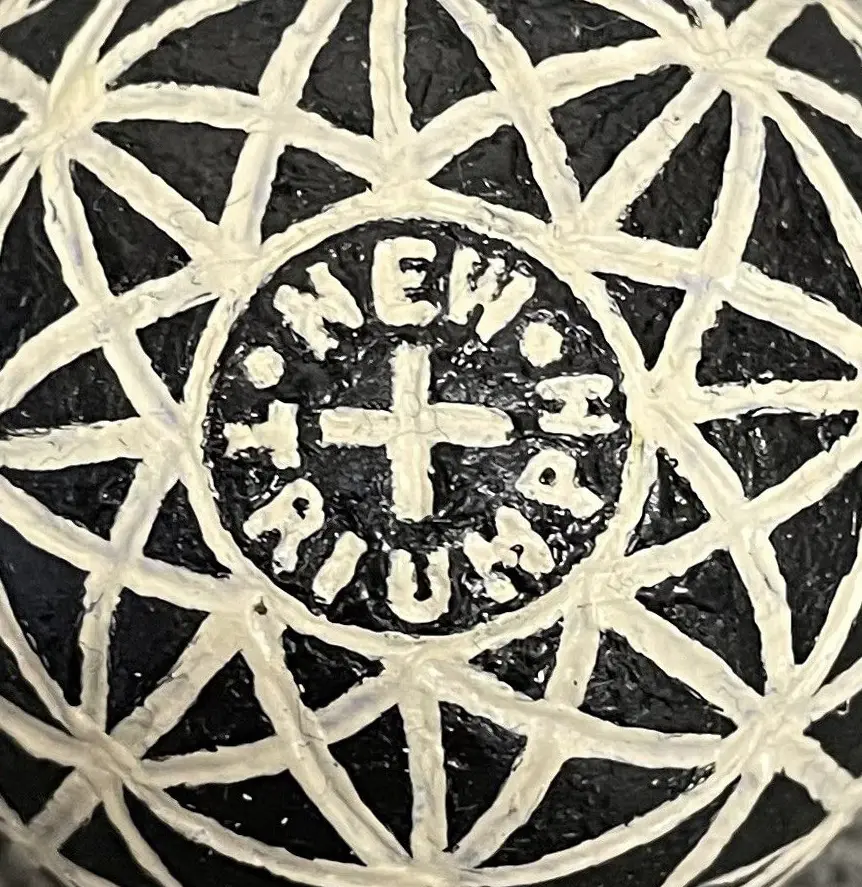

The Aerial is on the right in the accompanying two-ball image. Shown on the left is the back of the Vaile ball already discussed. Both Balls have never been painted except for the paint in the pattern lines. On November 18, 2022, the Scientific Materials Testing lab of Tempe, AZ, tested the beige surface of the Aerial ball using Fourier Transform Infrared Analysis and detected only polyisoprene and no paint nor any other organic matter, confirming that the Aerial ball does not have any paint or dirt etc. on its beige polyisoprene surface. The Aerial is shown here with the Vaile ball because their covers appear to be made from similar material. Both are the same beige color, uneven and rough across their surfaces, and the covers of both balls sound muted and soft, like they are made from rubber, when they are bounced. None of these characteristics are normal for molded rubber core balls with gutta percha covers made in the 20th century.

Both balls have been x-rayed and there is a wound rubber core inside each one. It is a relatively simple process, however, to tear a cover off an old golf ball and install a new one. Recovered and remade golf balls were produced in large numbers during the early 20th century. Back then, either gutta percha or balata was initially molded into thin, smooth shells. Each shell would cover half a golf ball. After the shells were formed, a used wound rubber core was placed inside a pair of shells and the shells were melted/molded/fused together around the core inside a heated ball mold. The exterior of the new cover bore the pattern on the inside of the mold.

One way to install a new cover and pattern on a wound rubber core today is to thickly coat the inside of each half of a two-part soft mold with rubber molding material. Then set the core into the mold, close the mold under a bit of pressure, and let things cure. If the mold had a pattern, it will be reproduced in mirror image on the ball. If the mold did not have a pattern and the ball came out with a perfectly smooth cover, then a pattern could be engraved and/or stamped in place. Of course, in this digital world we live in, complete with 3-D printers, CAD programs, laser engravers, stencils, and much more, there are other ways (see section 5.1).

Given that genuine Vaile balls date to the early 1900s and were made with gutta percha covers—as were the vast majority of all the balls made prior to the early 1920s—and this Vaile does not have a gutta percha cover, it appears to be a recovered ball. While there is no known Aerial ball with this pattern in an original early 1900s white paint, nor is there any record of such a ball in the 19th and 20th-century literature of the game, nor are there any other known early 1900s golf balls sans paint that match the texture and color that these two balls share in lockstep, the evidence indicates to me that both balls have old cores and new covers, and that their cover patterns were not created in a mold.

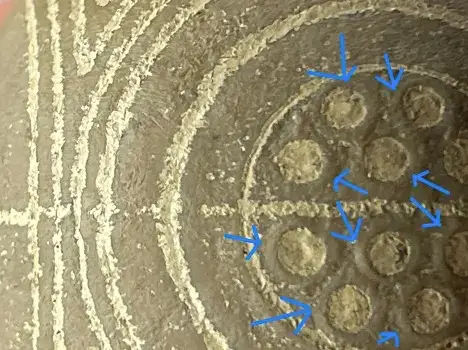

This is further confirmed by the closeup image with the blue arrows. These arrows show how the dimples on the Aerial ball were formed by something like the flat tip on a metal punch that was pressed into and then displaced the rubber, thereby creating the raised rings around the dimples as they appear in the accompanying image. Such raised rings have never been seen on any of the myriad of genuine balls with dimples that I have seen.

The blue lines in this image show how the lettering is incorrectly oriented to the crosshair design inside it. Also, “Aerial” almost touches its surrounding outer circle while “The” is much further away from the outer circle. Such asymmetry is not consistent with the work of an early 20th-century ballmaker.

This closeup image also shows how the cover itself is uneven and rough, and the lines marked on the surface of this ball are not consistent with the molded lines on an unused early 20th-century ball.

As mentioned earlier, on November 18, 2022, the Scientific Materials Testing lab of Tempe, AZ, tested the beige surface of the Aerial ball using Fourier Transform Infrared Analysis and detected only polyisoprene, not paint. Furthermore, after the ball was wiped with isopropanol and tested again, FTIR did not detect dirt, organic matter, or water on the cover of this ball like it did on the unpainted covers of five well-documented early 20th-century balls that also had their covers prepped and tested at the same time. This ball is clearly unused and exactly as it was made. Neither the rough surface nor the shallow-to-non-existent etched lines on the cover are the result of any sort of deterioration, nor are they consistent with early 20th-century golf balls.

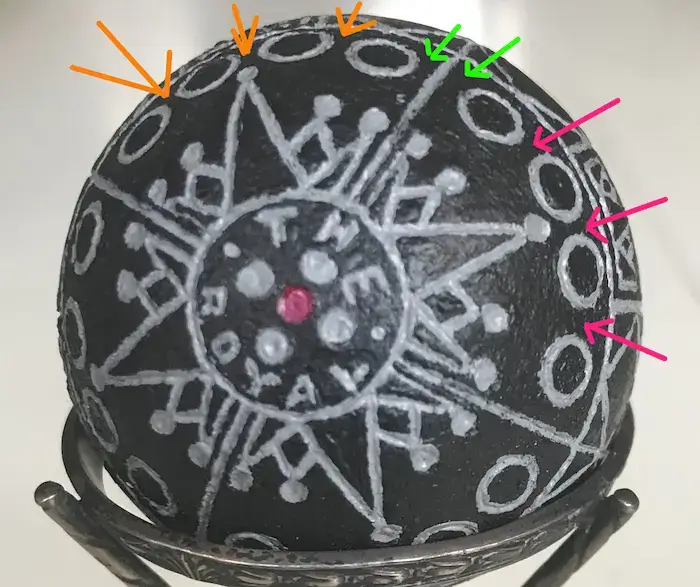

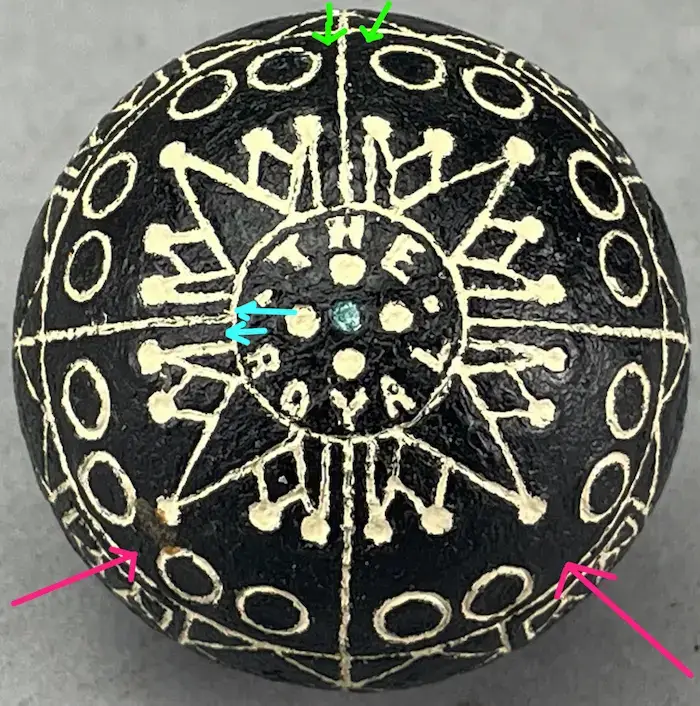

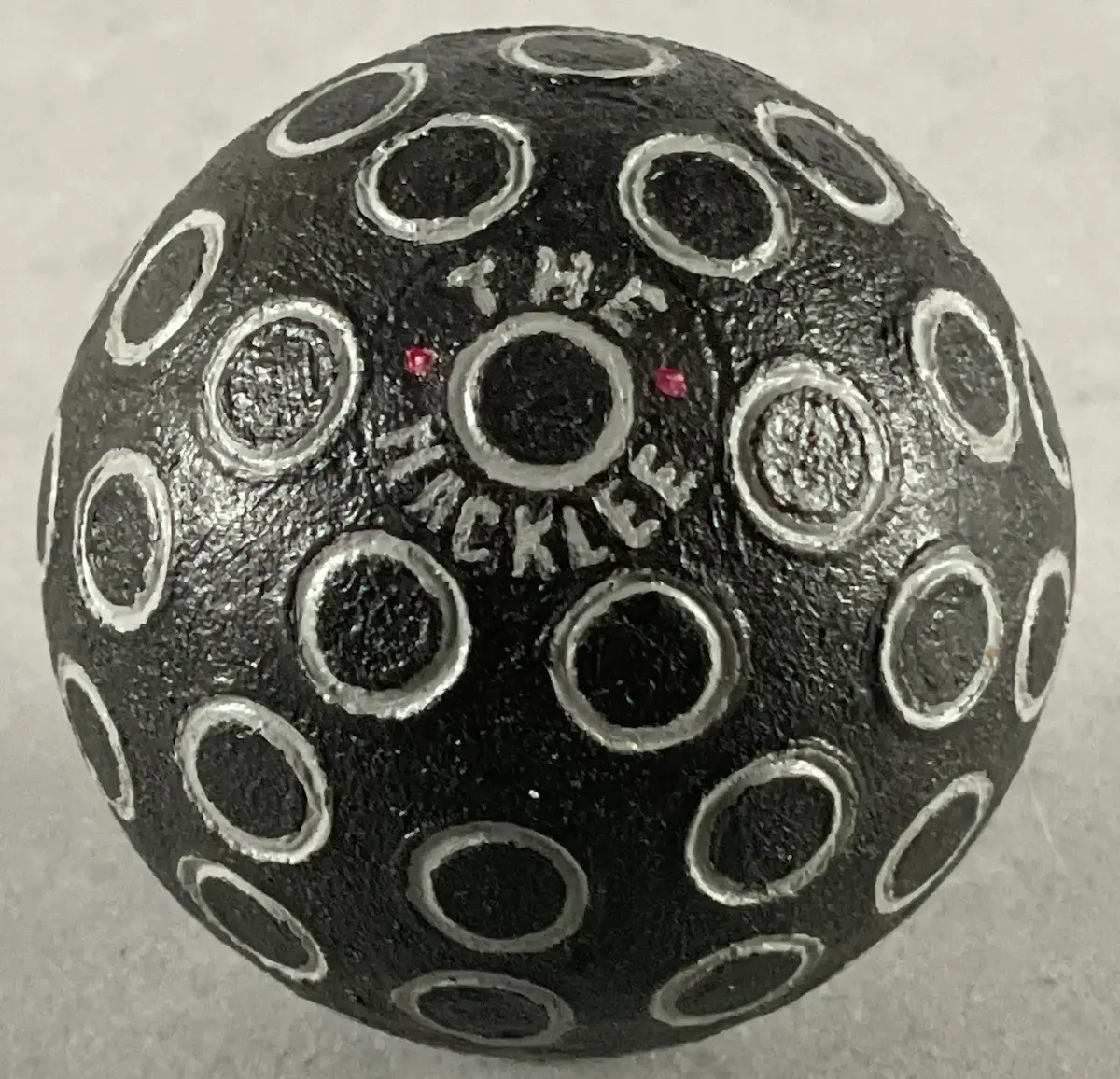

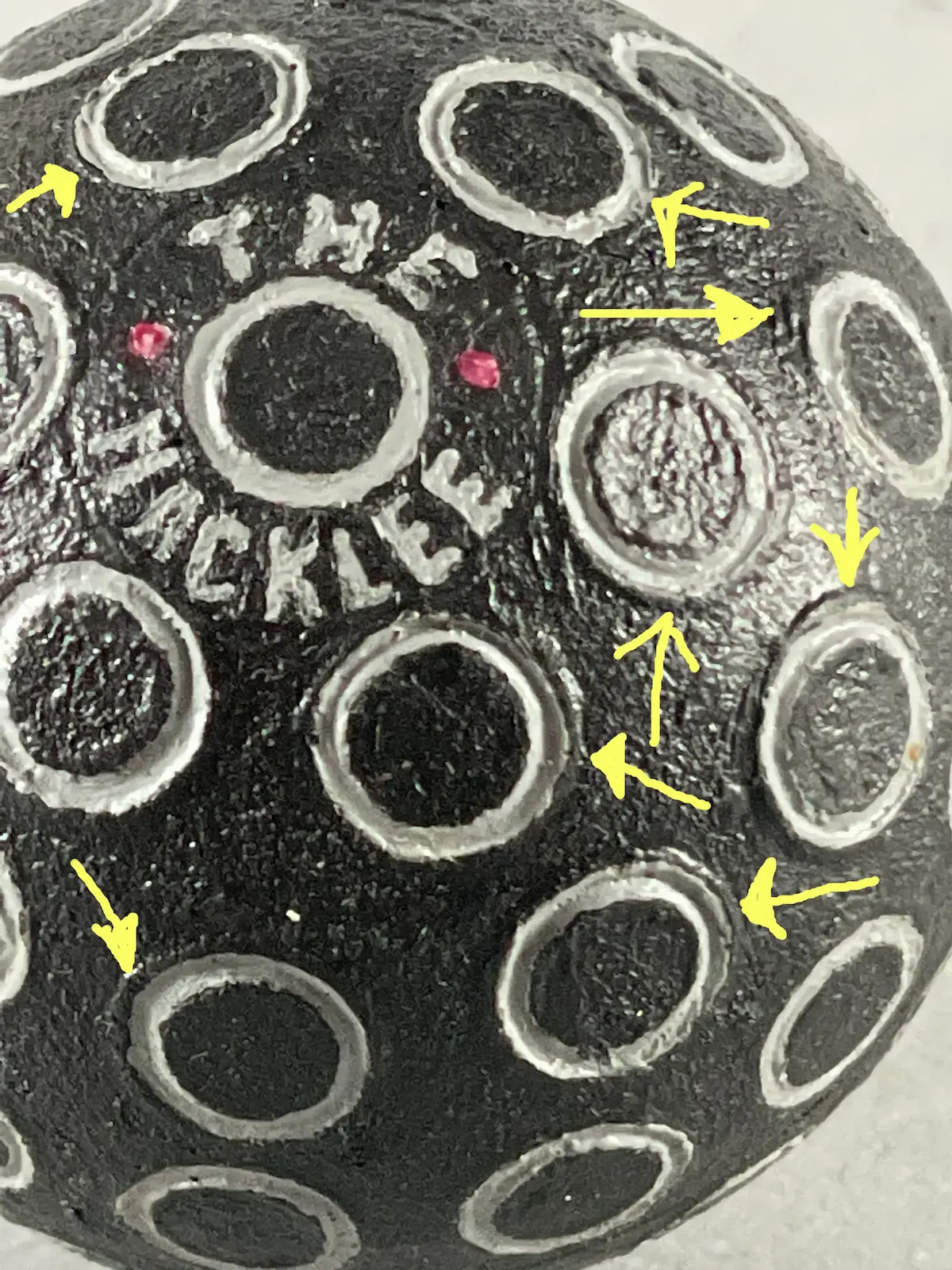

This black-painted Royal ball—which I have never seen in original white paint and was unable to locate in any 19th or 20th-century literature of the game—possesses several elements that are not consistent with golf balls made in the 19th or 20th century.

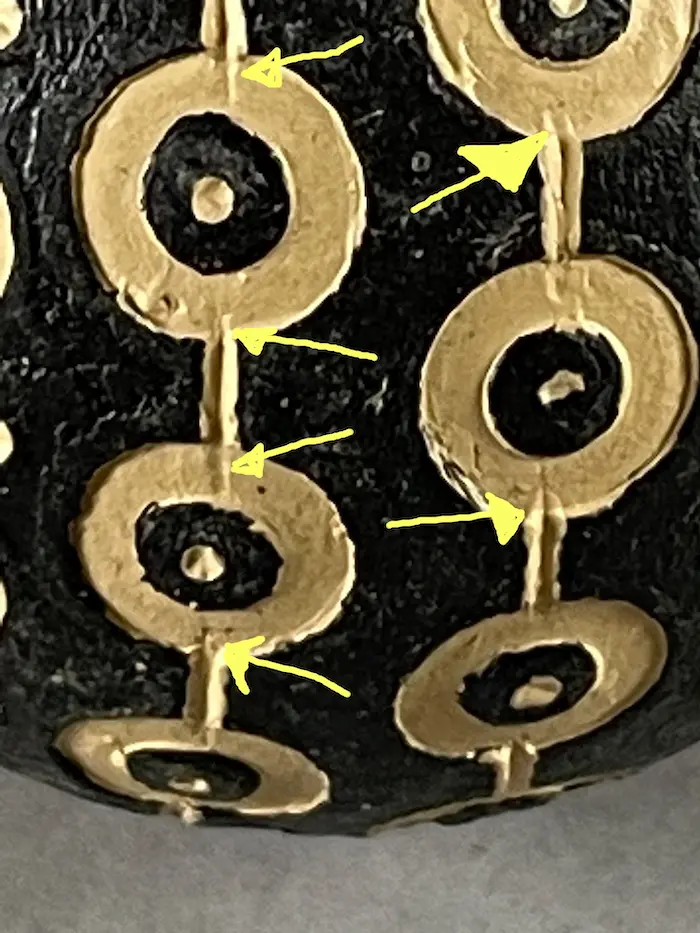

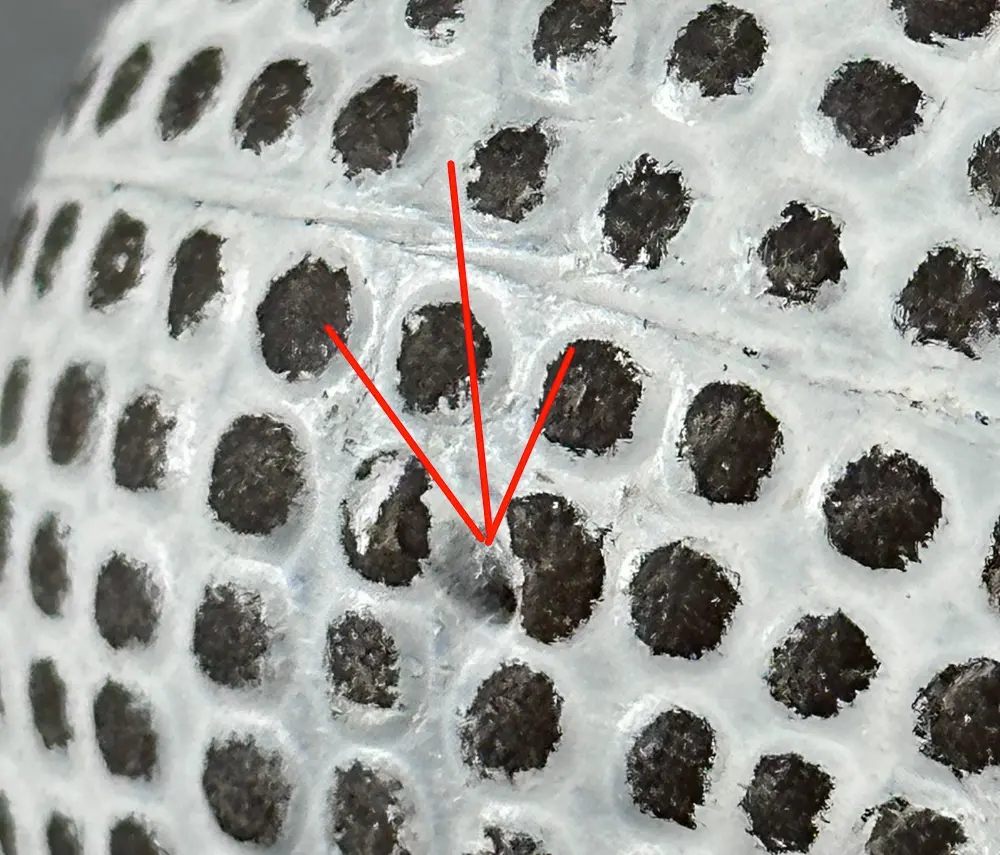

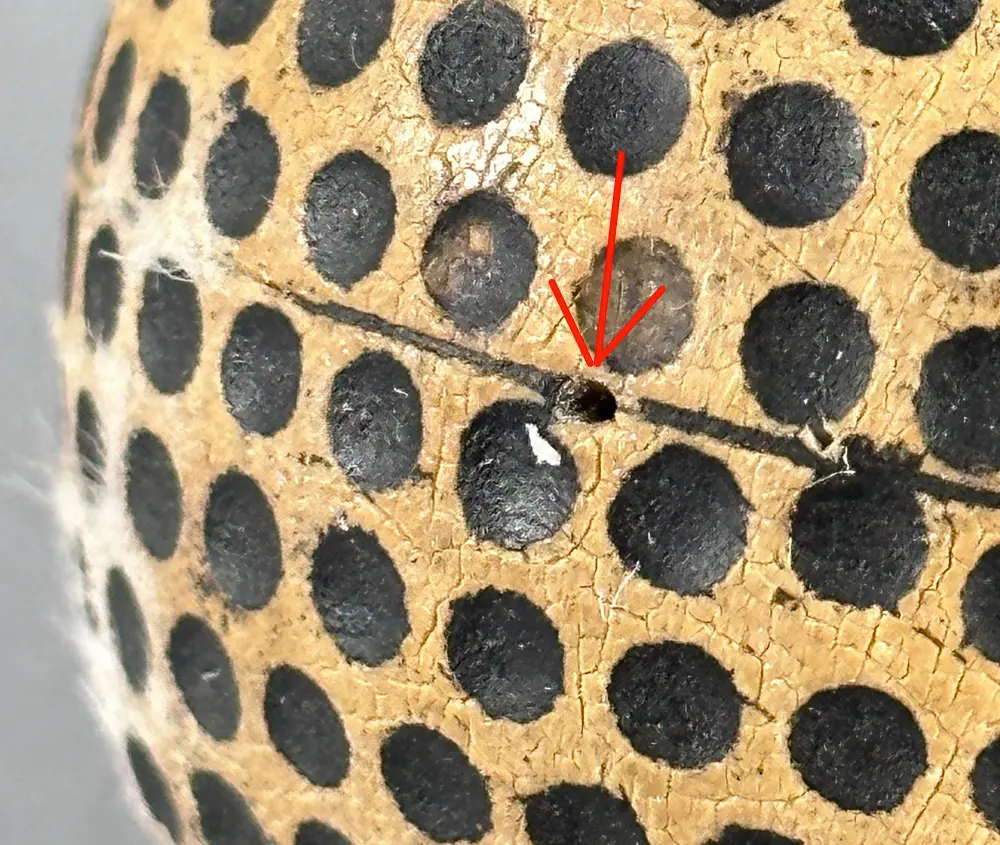

As pointed out by the green arrows above, there are raised circles next to the incised circles on the cover. This is consistent with stamping/engraving, not molding. As the stamp or engraving tool presses into the ball, it displaces the material underneath it which then rises around and above the perimeter of the stamped/engraved design. And that needs to be dealt with because it’s not normal. On a molded ball any excess material is forced out of the mold when it is closed under pressure, and the cover where it borders the pattern is always perfectly smooth when it comes out of the mold. Hence, some of the raised circles on this Royal ball appear to have been flattened—pushed back down after they were formed.

The light needs to be just right to see these raised circles, but they are definitely there and consistent with other raised perimeters on other black painted balls yet to be presented (see Section 3.8, 3.9, 3.10, 3.11, and others.) Note, also, that the raised but flattened circles are often off set from the perimeters of the incised circles that remain. I believe this is because some of the first circles stamped/engraved into the ball were out of position, so the heated material was pressed back down in an effort to make the circle disappear and a new circle could be more accurately installed in the cover. The Jockey ball in 3.8 also has similar issues with its pattern—horseshoes that were stamped out of position. Instead of covering them over, however, the worst horseshoes were simply stamped again, over top but slightly offset from the initial stamp, in an effort to hide the overall asymmetry of the pattern.

The image above left shows the relatively symmetrical lines that form the 5 diamonds on one quadrant. The image above right has two red lines that show the misaligned pattern lines used to form the diamonds on a different quadrant of the ball. These two images and the one above them show closeups of the painted surface of the ball. Its rough surface is not consistent with the smooth surfaces on early 20th-century golf balls.

Also, as can be seen in the first of the two images above, the spacing of the circles around the perimeter of is neither consistent nor even as shown by the red and green arrows. On the second image, the blue arrows call attention to the inconsistent spacing of the spires in relation to the lines that divide the ball into four quadrants.

When the first Royal Ball above is viewed next to the second, the first ball has completely different spacing inconsistencies. On the second Royal, efforts were made to evenly space the perimeter circles as opposed to the first ball where the circles are spaced in groups of two. The “R” in Royal in relation to the crown underneath the R is different between the two balls. Plus, there are more inconsistencies.

In short, the decorative pattern on the two balls does not match, so they did not come out of the same mold. Furthermore, their patterns and are not consistent in their execution with the molded patterns on antique golf balls.

Placed next to the unpainted Aerial ball, the black-painted Royal ball has a small nick in its side. The exposed material under the paint is not consistent with the dark brown gutta percha used to make early 20th-golf ball covers (see Chapters 1-2). Instead, the material underneath the Royal’s paint appears to be the same beige color as the material used to make the cover on the Aerial and Vaile balls shown earlier.

This Royal and the Aerial and Vaile balls shown earlier all share a muted rubbery sound when lightly bounced on a hard surface.

On November 18, 2022, the Scientific Materials Testing lab of Tempe, AZ, tested the black-painted Royal ball using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. FTIR analysis showed acrylic paint on the surface. FTIR showed that the white paint underneath the black paint bordering the chip was also acrylic paint “suggesting an acrylic primer and acrylic topcoat.” The material under the paint tested as part cis and part trans polyisoprene.

According to the report, “The Royal interior spectrum contains characteristics of both cis and trans polyisoprene.” A mixture of both cis and trans polyisoprene is most commonly consistent with synthetic isoprene per Comprehensive Polymer Science and Supplements written by Frank Bovey. In other words, according to the mixed trans/cis spectra documented by FTIR analysis, the cover on this ball is most likely synthetic rubber. It should be noted that FTIR cannot identify the difference between natural and synthetic polyisoprene, because both natural and synthetic versions have the same chemical structure.

Where FTIR testing leaves off, physical testing can take over—and there are major physical differences between organic gutta percha and synthetic polyisoprene as found in the golf ball covers I studied, specifically how they look, sound, feel, erase, cut, flex, melt, burn and smell, to say nothing of their color. Synthetic polyisoprene is petroleum-based, and the decorated cover samples that I stripped and heated up (in a spoon held by a vice) with a small propane torch, smelled like burning oil, and it was strong.

Penny Couteur, PHD, and Jay Burreson, PHD, write about cis and trans polyisoprene and golf balls in their 2004 book, Napolean’s Button’s: How 17 Molecules Changed History

“The trans isoprene polymer occurs naturally in two substances, gutta percha and balata. About 80 percent of gutta percha is the trans polymer of isoprene. (When harvested, gutta percha also contains resins, pigments, moisture, and impurities with little to no cis present, JBE.) Both gutta percha and balata can be melted and molded, but after exposure to the air for some time, they become hard and hornlike. As this change does not occur when these substances are kept under water, gutta percha was used extensively as underwater cable coating during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries […]

“The peculiar properties of gutta percha and balata are probably most appreciated by golfers…. In 1848 the gutty was introduced. Made from gutta percha that had been boiled in water, molded into a sphere by hand (or later in metal molds), and then allowed to harden, the gutty quickly became popular. But it too had disadvantages. The trans isomer of isoprene tends to become hard and brittle with time, so an old gutta percha golf ball was likely to break up in midair. The rules of golf were changed to allow play to continue if this happened by substituting a new ball at the position where the largest piece of the old ball had fallen. At the end of the nineteenth century, isoprene’s cis isomer also invaded golf when a ball with rubber wound around a gutta percha core was introduced; the cover was still made of gutta percha.” [Penny Couteur & Jay Berreson, Napolean’s Button’s: How 17 Molecules Changed History (Tarcher, 2004), 147-148.]

“Thus gutta percha and balata, trans isoprenes, are hard, inflexible masses, while rubber, the cis isoprene, is a flexible elastomer.” (Ibid, 151)

Synthetic polyisoprene was first sold as a commercial product in 1960 by the Shell Chemical Company. A few years later, synthetic balata (and Surlyn, a synthetic resin) took over for the organic stuff in the production of golf ball covers. Today, synthetic polyisoprene is widely used in the world of molded goods to make tires, rubber bands, engine mounts, belts, hoses, shoe soles, and much more.

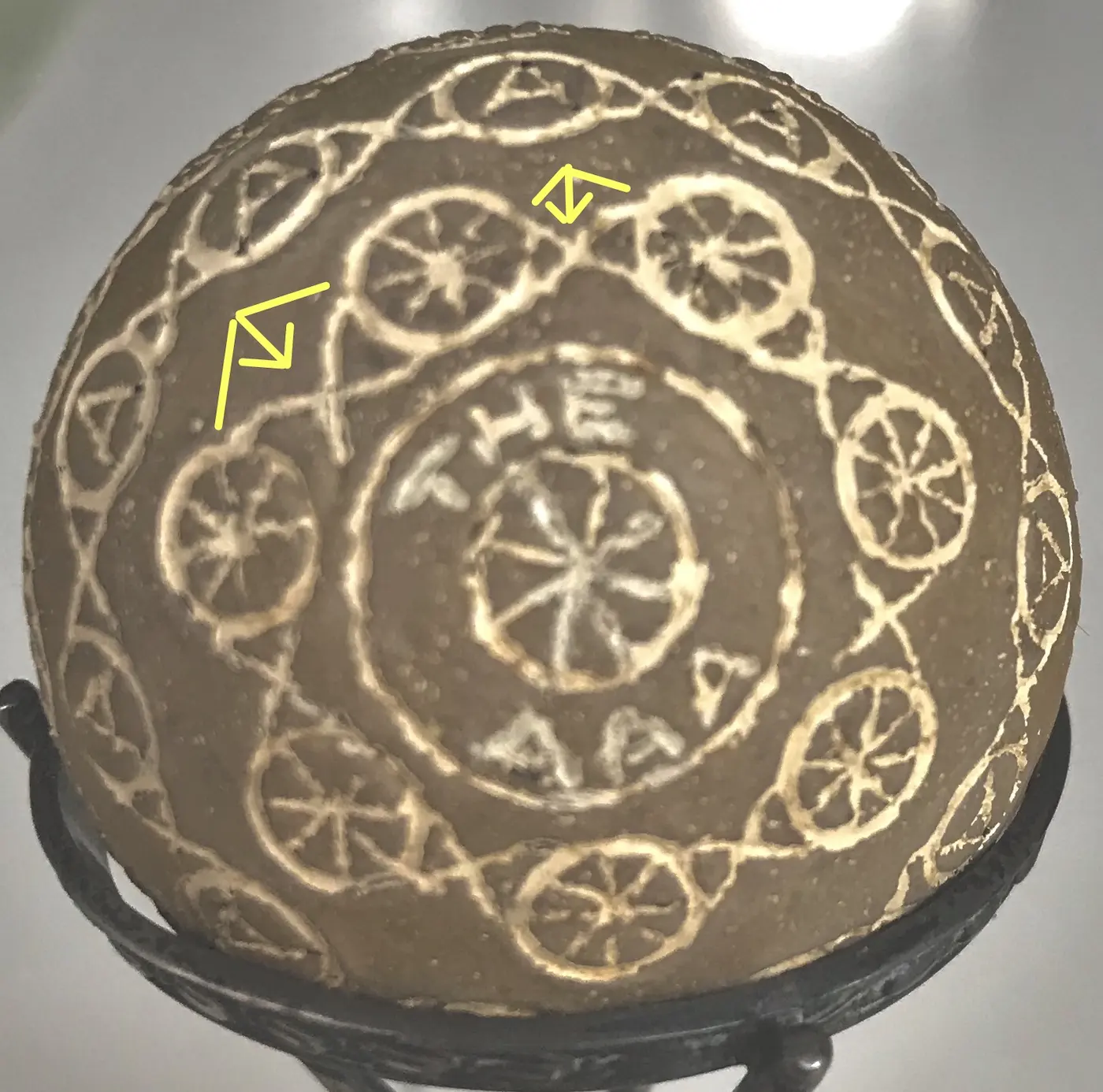

The yellow arrows and lines in the AAA ball shown above call attention to the inconsistent spacing between a number of the wheels. The brown unpainted portion of the surface on this AAA ball appears to match the brown unpainted portion of the surface of a Vaile ball shown earlier and again below.

For the record, I have never seen any reference to an AAA ball with this pattern in either the 19th or 20th-century literature of the game, nor have I ever seen or heard of any verifiable antique ball with this pattern.

The red arrows on this AAA ball call attention to the uneven spacing between the dimples. The green and yellow arrows call attention to the uneven spacing between the circles. The left yellow arrow also points to what appears to be beige material where the black paint has chipped off. See the New Hawk (exposed chip in paint), Aerial, Vaile, Why Not, and Royal balls for similar beige material.

The blue arrow calls attention to what appears to be a raised surface around the stamped circle. The light must be just right to see such an anomaly as is found on a Royal ball presented earlier.

Below is the same image as shown above without the arrows, so the inconsistent spacing of the dimples is easier to see.

For the record, I have never seen any reference to an AAA ball with this pattern in either the 19th or 20th-century literature of the game, nor have I ever seen or heard of any verifiable antique ball with this pattern.

Once again, two different black-painted balls have patterns that do not match. The red lines point out a few of the anomalies that deal with more than just paint. Underneath the paint the lines on the first ball (Image 1) do not appear to be as deep or wide as those on the other ball (Image 2). The ball on the left sold on eBay in 2019 and the other was offered on eBayUK in 2023.

For the record, I have never seen any reference to an Anderson ball with this pattern in either the 19th or 20th-century literature of the game, nor have I ever seen or heard of any verifiable antique ball with this pattern.

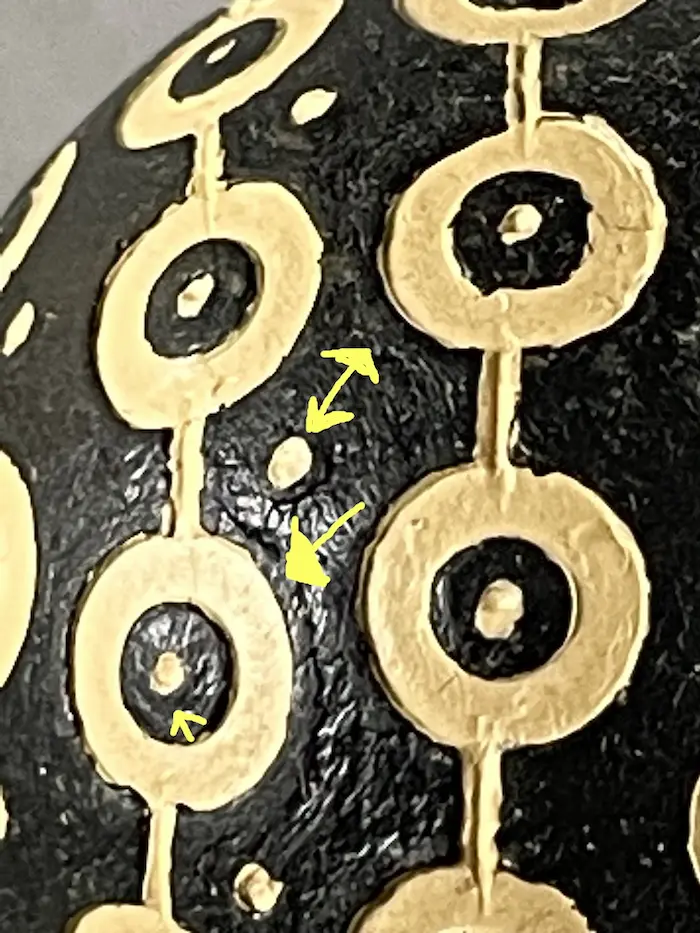

This black ball possesses several anomalies. Both poles have inconsistent spacing between the horseshoes and the lettering. A double-stamped horseshoe is shown second from the left in the image below.

Above and to the right, the horseshoes appear to have a raised outline around them, which can be seen only if the light is at the right angle.

This is consistent with stamping, not molding, a design into the cover. As the stamp presses into the ball, it displaces the material underneath

it which then rises around and above the perimeter of the stamped design.

The horseshoes are not evenly spaced or even at the same height when viewed from one to the next around the circumference of the ball, nor are

they all oriented correctly.

As shown in the image to the right, the two horseshoes third from the left in the second and third row from the bottom have the paint-filled

remains of a second horseshoe stamped underneath.

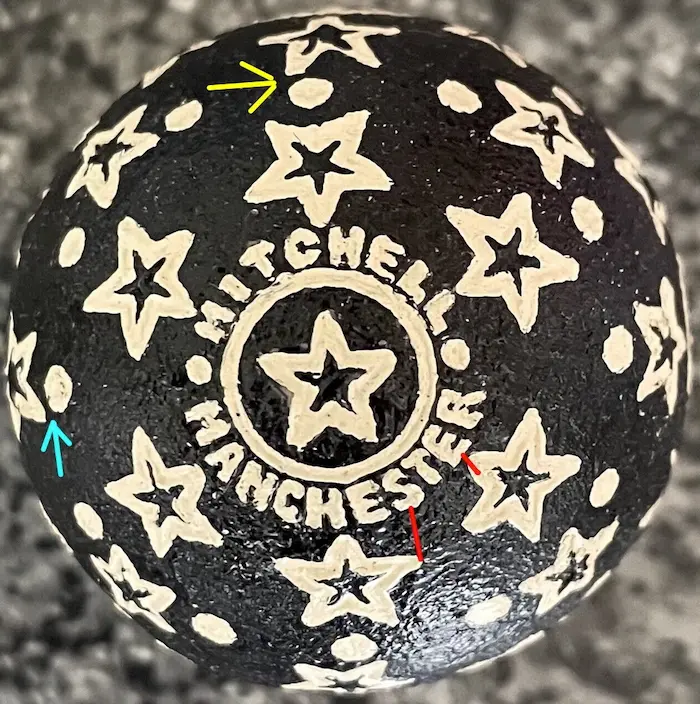

These black-painted Shamrock balls do not match. The 4-leaf clover in the center has its stem pointing to the left while the other has its stem pointing down. In addition, the clovers on each ball are not in the same location. This is easily seen if one just looks at the clovers closest to the “T” and the “H” in “THE” as well as the rest of the letters in the name. Furthermore, the names and shamrocks are different sizes. The name on each ball above is on only one pole.

Shown below are the reverse poles of two additional Shamrock balls. The first ball here is marked “Shamrock Ball” in a ring that matches the one on its reverse pole, marked “Mitchell Manchester.” Both balls are different from the two shown above. Notice the raised perimeter around the shamrock as shown by the red arrow below. This is not normal. See 3.4 and 3.10 to learn how this indicates that the shamrock design was stamped, not engraved in place.

One of these appears to be painted black (Image 1). The other (Image 2) appears to be unpainted “white gutta percha” (white gutta percha is often yellow in color, not white—see 1.2). The crazing and cracking on its surface, easily seen to the immediate right of the name circle given a closeup view, is clear evidence confirmed by the plastic look of the cover that the cover is made from gutta percha. Once again, in keeping with many of the black balls that I have reviewed, the name is bigger on the black ball than it is on the unpainted ball, both of which have the same “Mitchell Manchester” name layout on their respective poles. (For more on such name/pattern size differences, see 2.1 Stars & Stripes.)

To review, the three black shamrock balls all have different patterns and none of them match the pattern on the Shamrock ball in Image 2 with the unpainted gutta percha cover.

If unsure that a ball is recently painted black, rub that ball on a clean sheet of white paper to see if black paint rubs off. Rubbing a black-painted ball on white paper will usually leave black marks, especially if it has been painted in the last few years. Also, the cover will look like its painted when viewed under a loupe. Worn, oxidized, or distressed gutta percha can leave dark brown marks if rubbed on paper. If in good condition, the gutta percha will leave no marks. If the cover is bare gutta percha, it will typically have evidence of crazing, etc. when viewed with a jeweler’s loupe.

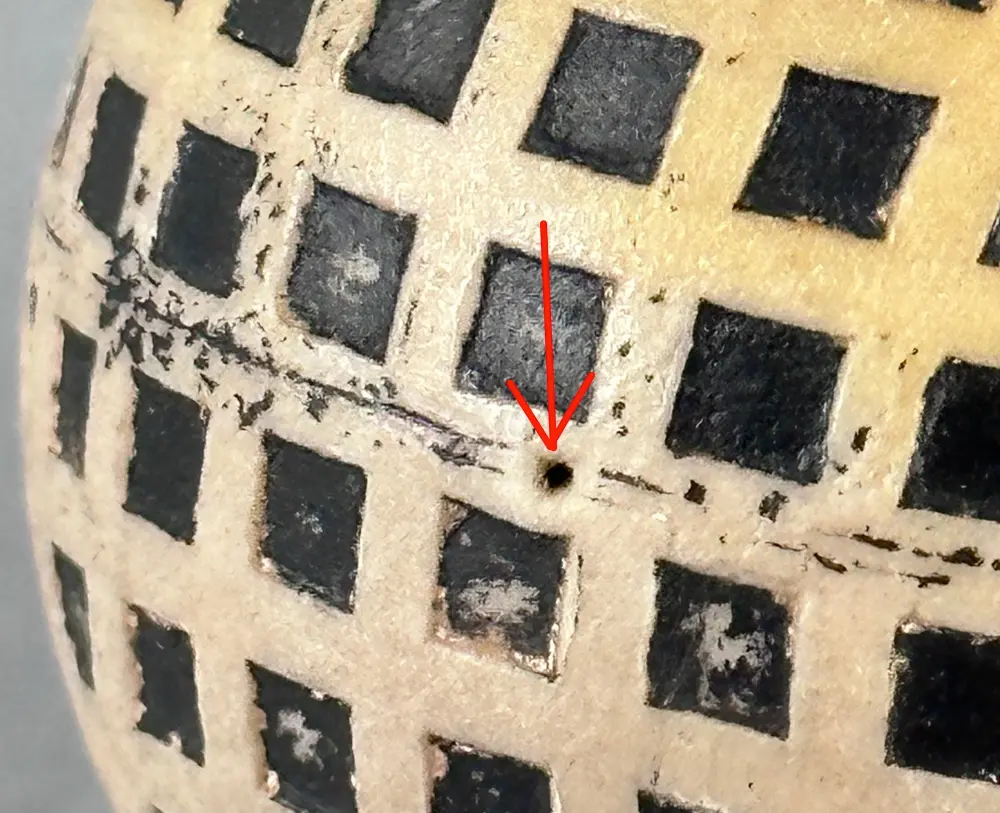

A close-up view shows that the name is engraved. With the light angle just right, raised rings around the large circles and small dimples can be seen. Furthermore, the lines connecting the circles vary in depth and lack symmetry, plus they often cut into and below the circles themselves. None of these things are consistent with a pattern produced in a mold.

A cover with circles, dimples, and lines cast in a mold would look different. Instead, any displaced material made by the pattern inside the mold would exit between the top and bottom half of the mold as it is closed. The flat surfaces of the finished ball would be perfectly smooth, and the lines would be uniform and stop at the exact edge of the circles. The connecting lines would also be the same depth as the circles, not deeper than the circles as can be seen below.

For the record, I have never seen any reference to an Emperor ball with this pattern in either the 19th or 20th-century literature of the game, nor have I ever seen or heard of any verifiable antique Emperor ball with this pattern.

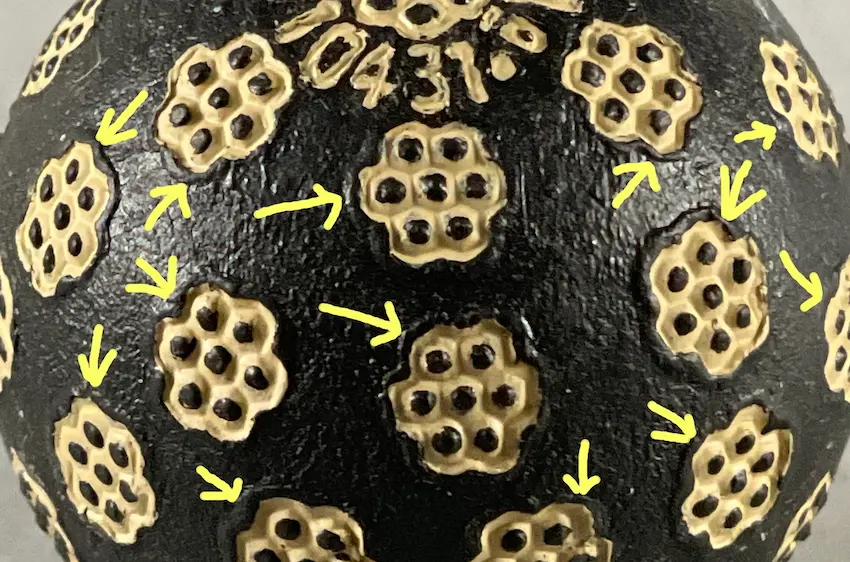

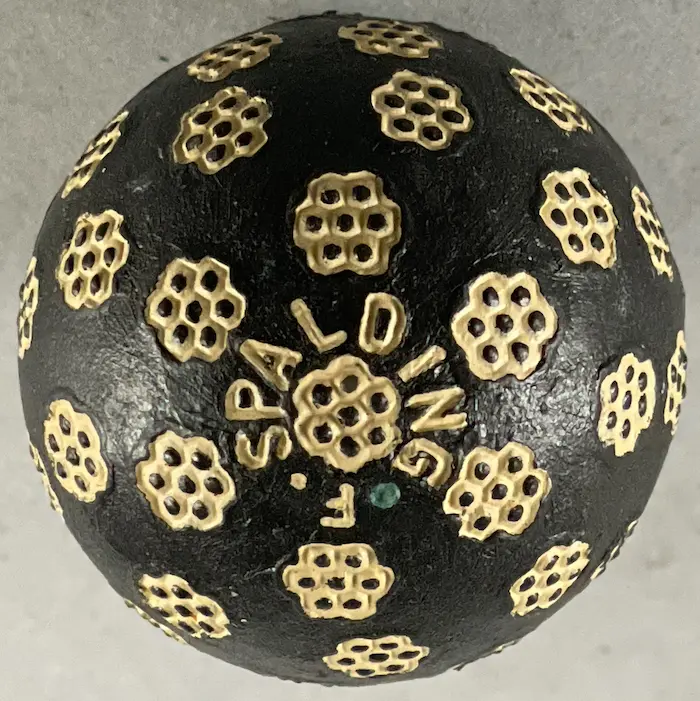

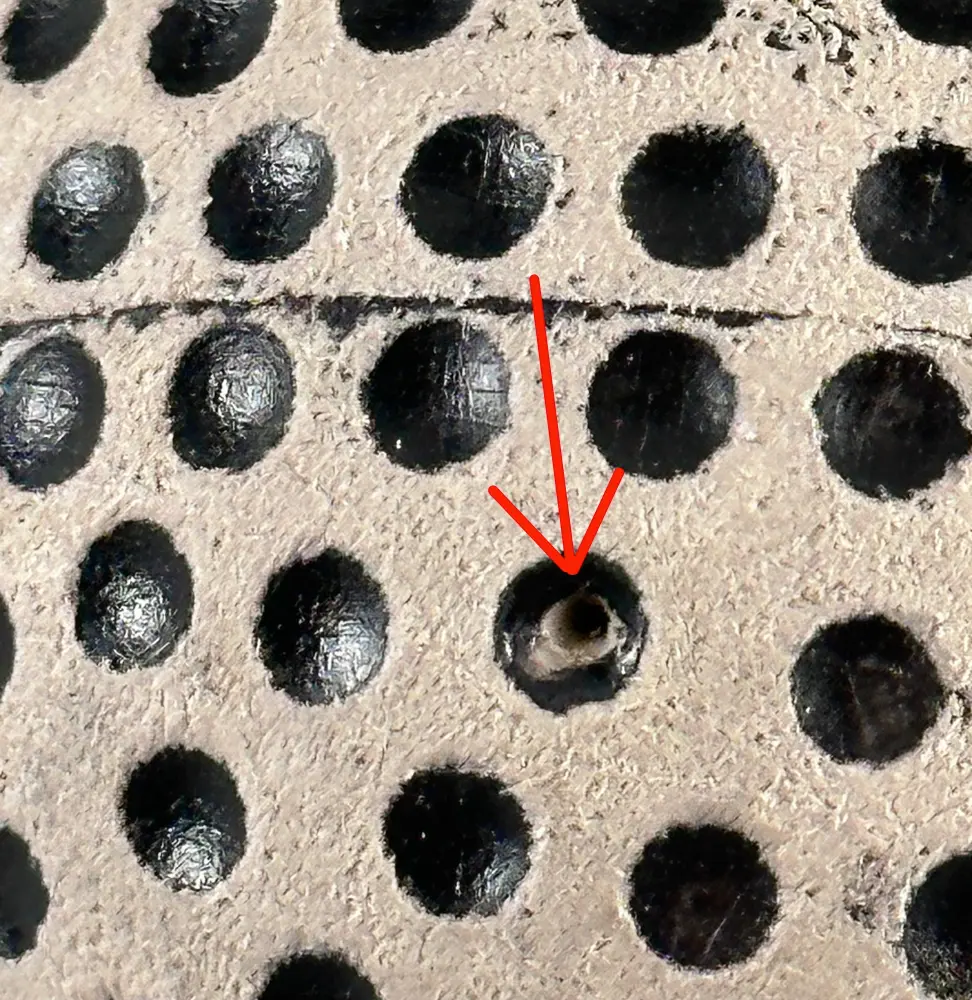

The cover on this Spalding F ball has a raised perimeter around each of the honeycomb or flower designs.

Such raised perimeters are not consistent with antique golf balls in original paint. This is because the patterns on all twentieth-century golf balls were built into the molds and not stamped into the ball after it was molded. Consequently, on some of the decorated balls, such perimeters were pushed down and flattened to a degree, other times they were removed, and still other times they were left untouched and as plain as day like they are on this particular ball. See 3.4, 3.8, 3.9, and 3.10 for more on this.

Below is a second Spalding F with the white fill paint. It does not match the adjacent ball with the cream-colored fill paint: